London’s Somerset House comes to life in winter. Its illuminated neoclassical façades form a sparkling backdrop to the open-air ice-rink that, each year, attracts thousands of pre-Christmas revellers.

Until the end of the 20th century, it was a more austere place, housing many government departments, including the Inland Revenue. That changed in the 1990s, when the Somerset House Trust was set up to develop the building and its open spaces for public use. The civil servants moved out, the car park was replaced with fountains, and upmarket restaurants and art galleries occupied former offices.

Historic heating

Credit: Weber/Shutterstock

Originally, heating at Somerset House came from many fireplaces throughout the building, as indicated by the numerous chimneys present on the roof. The CIBSE Heritage Group Archive indicates, in a 1932 catalogue, that the building was being heated by Beeston (hot water) Robin Hood Boilers and Radiators.

A 1900 catalogue of Robert Boyle & Son states that Somerset House was provided with Boyle ‘Air Pump’ Ventilators, which supplied natural ventilation. On the CIBSE Heritage website, a biography of Robert Boyle reveals that he was a fierce opponent of mechanical ventilation.

The Trust continued to open up the building over the next decade, introducing more eateries and event spaces, and letting out workspace to creative industries. But it had a problem that threatened to scupper its expansion plans. While Somerset House was in prime central London location, with room to expand, it had an outdated heating and cooling system that was struggling to keep up with the requirements of its growing number of tenants.

It suffered from poor electricity infrastructure and had two inefficient electric chillers, while the heating was being handled by 40-year old gas boilers running at 75% efficiency. The Trust realised it could not expand and open more restaurants unless it upgraded its systems; failure to do so would reduce potential revenue and limit its ability to maintain the historic building. This would be an expensive undertaking, however, made more costly and risky by Somerset House’s Grade I listed status. Electrical grid reinforcement alone was estimated at £1m.

The Trust’s remit is to turn Somerset House into a profitable enterprise and, any failure in the new systems would have an impact on its bottom line. To minimise its risk, the Trust turned to energy performance contracting (EnPC), whereby a company designs, buildings, services and HVAC systems while guaranteeing performance. In return, the client uses the energy savings to fund the investment.

Cynergin has completed EnPCs in the NHS and museum sectors, which means it designs, builds, finances and operates energy schemes, and takes on all the risks of performance. For the public sector there are procurement frameworks with established contract models and tendering processes. The frameworks feature EnPC service providers that have proven expertise in developing a project, plus a track record of honouring guarantee commitments. (See panel, ‘How energy performance contracting works’).

Because of the building’s listed status, the heat-rejection units and adiabatic condenser could not be sited in any visible area

EnPC frameworks are increasingly being used by local authorities, museums and universities. Somerset House Trust turned to Cynergin to provide an energy solution that would meet its heating and cooling requirements, while reducing its capital costs and minimising energy bills and its carbon footprint.

Technical director Keith Nord examined the energy profiles and likely future energy demand of Somerset House, and came up with a solution that mixed efficient new plant and existing pipework and chillers. ‘There was an existing chilled water circuit and this has been incorporated into the new, extended system to ensure the absorption chiller is used as effectively as possible,’ he says.

Director of sales Howard Stone adds: ‘There is no point throwing out perfectly serviceable assets such as the existing chillers. As we are technology independent we propose the right solution for the project that produces sufficient savings, such as the absorption chiller supported by the existing chillers.’

It recommended installing two new high efficiency boilers running at 95%, and a 530kW gas-fired CHP as the primary source of heat and electricity, which could run in island mode in the event of a power failure.

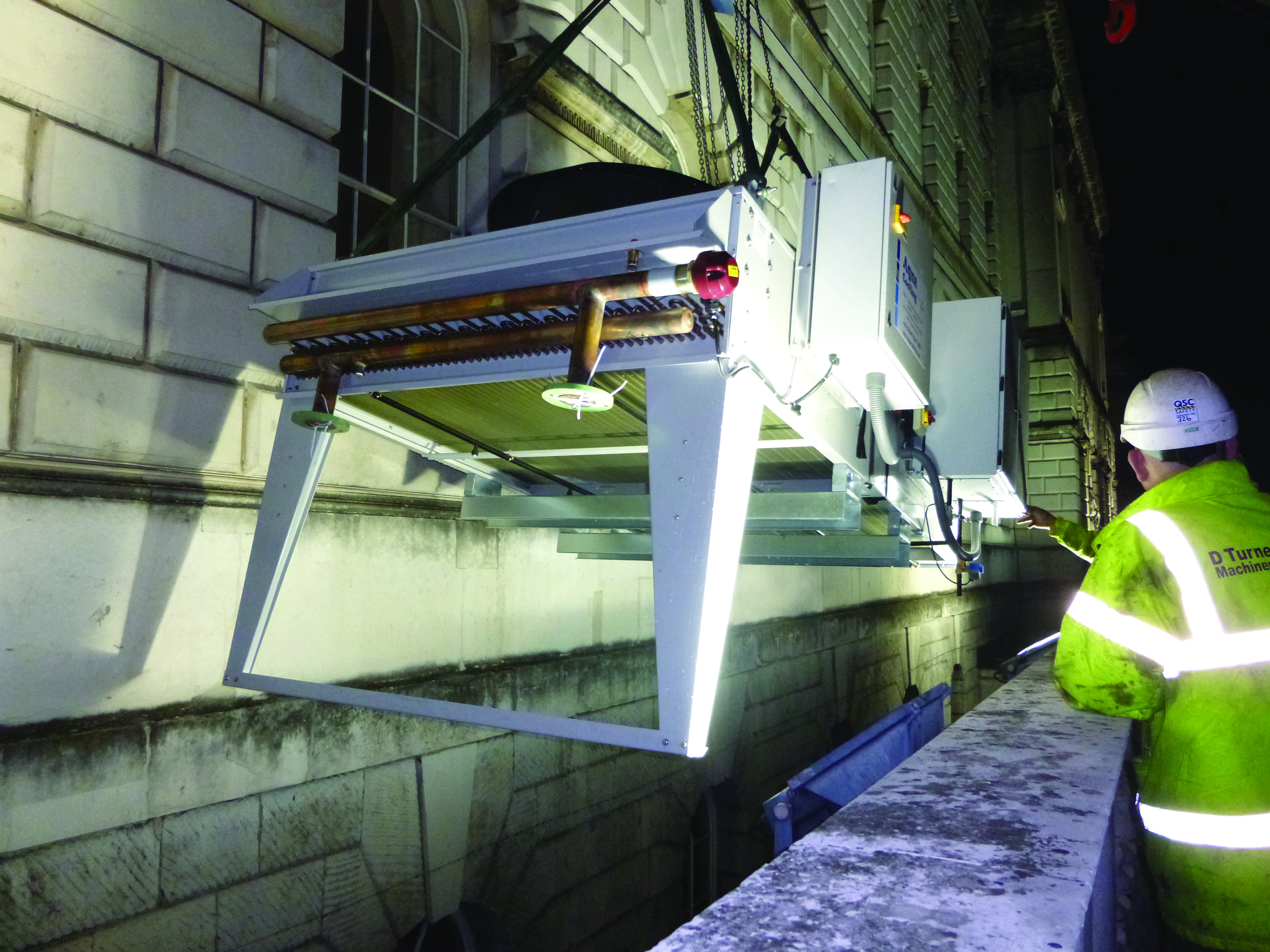

Heat rejection units are craned into a light well hidden from public view

Eyelets from anti-bird netting had to be removed to fit the units

The excess heat from the CHP is being used to provide cooling, via an absorption chiller, thus creating a combined cooling, heat and power system. This satisfies the requirement for air conditioning in the new restaurants, as well as providing an efficient cooling system for the building. The existing chillers have been retained, but will only be used to top up cooling on warm days, as they are more expensive to run. There is a new chilled water ring main and an enhanced control system to run systems more efficiently.

Working within the fabric of the 200-year-old building was a major challenge. One substantial technical difficulty was the positioning of the heat-rejection units and the adiabatic condenser for the absorption chiller. Because of the building’s listed status, these could not be sited in any visible area.

‘There were no roof areas suitable as they had to be out of sight, and ground space is very limited. As a result, they are concealed in a light well,’ says Nord. This had sufficient airflow to provide the cooling, but was not visible from the exterior of the building.

Taking the heat rejected from the CHP and absorption chiller meant threading pipework through walls 1m to 1.7m thick. In load-bearing walls, lintels needed to be positioned above and below the opening to take the weight of the structure, before ductwork was installed. Removing old equipment was not straightforward either. The four 1.5-tonne old boilers had to be cut up before they could be removed from the boiler room, and bricks had to be taken out of an exterior wall to allow the CHP unit to be installed.

Space was also very tight in the light well, to the extent that a 10mm eyelet, securing anti-bird netting, had to be removed to allow the half-tonne, custom-made heat-rejection units to be placed in by crane. These units, and a new 1.2m header, are supported by an iron frame installed in the light well.

The success of an EnPC contract depends on getting the interface between installation, design and operation exactly right

Stone says the success of an EnPC contract depends on getting the interface between installation, design and operation exactly right. ‘Some EnPCs can get complicated. It is the interaction between the contract, finance and the technical design that is at the heart of what we do. If you don’t know how they interact, you can get in the quagmire pretty quickly.’

Cynergin offered Somerset House Trust a 15-year operation and maintenance contract, and a guarantee that the new assets would save it energy costs, from the former £600,000 per year to a projected £365,000 at contract utility prices. Annual carbon emissions are forecast to be reduced by 16%. ‘It’s a sizable return on investment with very limited risk,’ says Stone. The cost of the project was £1.8m.

Verification of the performance is essential within a EnPC contract, as the share of savings agreed between the energy service company and client is dependent on targets being met. The savings are measured to meet the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol. The company monitors projects from its Reading base and has service-level agreements with customers that stipulate response times to any faults in the system.

The new systems at Somerset House were switched on in time for the skating season, and performance testing starts this month. The building now has the infrastructure it needs for future expansion, a lower energy bill is guaranteed, and savings can be put towards making it an even more desirable destination for tourists and Londoners.

How energy performance contracting works

Since becoming an energy service company (Esco) in 2009, Cynergin has won many energy performance contracts, including those for NHS Foundation Trusts at Warrington & Halton Hospitals and Yeovil District Hospital.

To prove that the company had the financial, technical and management skills to guarantee the performance of HVAC systems, it had to meet the criteria of several frameworks, including the Carbon Energy Fund and Essentia.

The former funds, facilitates and project manages complex energy infrastructure upgrades for the NHS and public sector, while Essentia is the trading arm of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

‘These stand as NHS-endorsed business models,’ says Cynergin managing director Nick Ray. ‘If you fit within them – bingo! A lot of other public markets look at the standards set by the NHS, and think they must be pretty high.

‘It’s more than just a list; it’s a really pro-active business model. You can’t get on the list unless you know what you’re doing.’

To get on a framework, companies must demonstrate both a financial and technical understanding. ‘We are putting our money where our mouth is, so we have to assess the customers’ current position, identify the savings, and design a solution that fits within the financial model,’ says Ray.

To guarantee energy savings, the Esco must be rigorous in the way it designs, installs and maintains the system. ‘Performance is absolutely essential – our profit is critically dependent on it,’ says Ray.

As savings are shared with the customer, Ray says it is important to be as transparent as possible when bidding for deals: ‘The methodology by which savings are calculated are clear, and agreed with customers as part of the contract, so there can be no disputes.’

Although Esco companies have been around since the 1980s, Ray says the market is maturing as specialists learn to bring together the financial, legal and technical elements that need to be integrated to design and manage the contracts successfully.

‘I would say I have been working to this model for 20 years and, for a long time, we were ploughing a bit of a lone furrow because we were the only ones doing it,’ he says. ‘People thought it was too good to be true, but what has helped the market is the emergence of frameworks that are specifically for EnPC-type projects. You can’t get on there unless you are proven at delivering them.’

Ray believes EnPCs will only get more popular with clients who need to make carbon reductions but don’t have the capital to make the necessary investment. ‘They have pressing needs for their limited capital elsewhere. So if we can unlock it for them by bringing new money and a different approach and expertise – that shows there is a way to unlock it without having to do without the new scanner they need or the wing they want refurbished – it’s a great solution.’