To improve the balance of the handbook, there are significant new materials on technology and practice, and the chapters on light and vision from the previous edition of the SLL Lighting Handbook have been moved to the recently revised SLL Code for Lighting, which is also due to be published soon.

The resulting 480-page handbook includes 13 new chapters and provides a unique, well-balanced reference covering the considerations, technologies, processes and practices that unite to deliver a successfully illuminated environment.

This edition of the handbook was written by an army of volunteer authors, and then reviewed by a wide cross-section of practitioners. Lead author of the SLL Lighting Handbook Paul Ruffles emphasises in his handbook presentation2 that there was a concerted effort to ensure that the review process included younger members of the lighting community who were most likely to have more recently experienced training and applications of new technologies.

The 32-chapter handbook is divided into three sections and four appendices and, at first sight, the printed version can present a daunting prospect. However, Ruffles indicates that the book is not designed as an end-to-end read but is suitable to ‘dip into’ when lighting professionals (known as ‘lighters’) need to improve, or refresh, their knowledge of particular lighting topics.

The first section considers the ‘Fundamentals’, and is structured to follow approximately the design right through to commissioning and future maintenance. The second section considers ‘Technology’, and then the largest part of the handbook, which makes up the third section, considers a selection of ‘Applications’. There are important revisions to practically every part of the handbook. However, this CPD article is focusing principally on the new chapters.

Three of the five chapters in the design section are completely new to this edition: ‘Lighting design process’; ‘Design ethos’; and ‘Coordination with other services’.

‘Lighting design process’ considers why the lighting is needed – for example, it could be to meet any one of a diverse range of needs: for people; for objects in a museum for conservation purposes; for external events at festivals; or for one of the myriad other lighting needs. It also covers some of the key responsibilities that ensure the provision of successful lighting – who commissions the lighting, who is responsible for the lighting, and how to confirm that the final lighting installation meets the need of the end user.

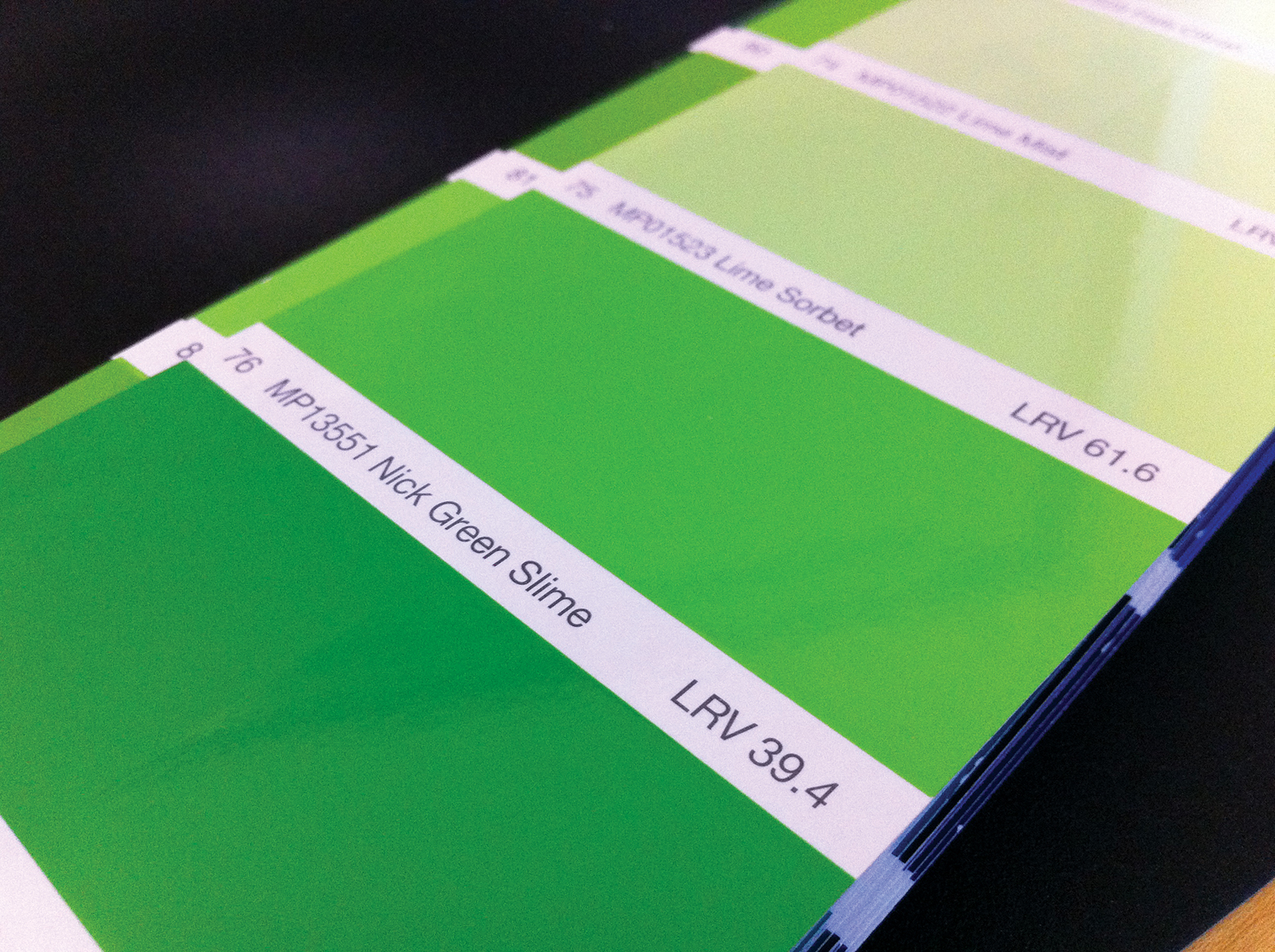

Figure 1: The light reflectance values as reported on a paint swatch. The light reflectance value ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 representing pure black (that is, not light-reflecting at all) to 100.0, pure white, with all the light being reflected (Source: SLL Lighting Handbook)

Beginning with the CIBSE code of conduct, the ‘Design ethos’ chapter goes through how the lighter has a responsibility to the wider society as well as fulfilling the client requirements. The ethical responsibilities align with those of many other professions, and are elucidated in this chapter in terms of considerations such as the Bribery Act; what is expected in tendering procedures; the practicalities of ‘equal and approved’ products; and aspects that will impact the sustainability of the lighting system.

The chapter ‘Coordination with other services’ is included to help guide the many people coming into the lighting profession from non-engineering backgrounds – such as theatre design, fashion styling or architecture – who may not be familiar with the demands of mechanical and electrical services and the challenges in using the shared space. This includes providing access and integration with other ceiling services, distribution of power cabling, and the interaction of cooling systems and the impact on the performance of lights.

Part 2 ‘Technology’ has been updated extensively and includes two new chapters – ‘Light sources’ and ‘Power to lighting systems’ – as well as incorporating significant changes to the ‘Controls’ chapter.

‘Light sources’ provides thorough coverage of the whole range of lighting technology that, as may be expected, includes a significant segment on LEDs, their construction, directionality and the type of light emitted.

The operational efficacy of LEDs is discussed, and this notably includes temperature sensitivity – as most traditional light source LEDs struggle to dissipate heat, and increasing the temperature at the LED can seriously reduce its light output, it emphasises the importance of the lighting design to maximise heat dissipation from the LED chip.

The extensive section on LEDs does not displace coverage of the more traditional lamp types, such as metal halides and discharge lamps, which are included complete with considerations of the peculiarities of each type – even extending to a short section on gas lighting.

The significant changes in the ‘Controls’ section were driven by the needs of lighters to understand the rapidly advancing area of electronic and digital controls. The energy consumption of a lighting installation can be significantly reduced by the addition of automatic lighting controls.

The handbook notes that they are ‘essential’ for design compliance with current Building Regulations and/or energy performance requirements, although ‘lighting performance should not be compromised in the sole interests of energy conservation’.

In his presentation, Ruffles reflects that ‘many of the problems with the application of LEDs has been to do with the electronics rather than the LEDs themselves’.

The Lighting Energy Numeric Indicator (LENI) is introduced as a reasonable starting point in lighting energy prediction, but notably ‘the actual energy savings will be governed by the specific application and human factors’.

The inclusion of a new ‘Power to lighting systems’ chapter reflects the importance of the rapidly evolving topic. Although it is not an electrical engineering chapter, it outlines the circuit design process, and how cables are installed and run through the building so that lighters are aware that designs must account for the realities of supplying power and routing cables.

There is a salient reminder early in the chapter that, no matter how complex a design is, there are two basic requirements associated with the distribution and use of electricity – the safety of people and ensuring that the risk of fire is not introduced. It goes on to describe final circuit distribution protection and effective cable length, something that is both important for emergency lighting and for DC-based systems such as LED lighting.

It discusses conventional and modular cabling systems, and the chapter closes with information on distributed power systems, with an overview of DC-based systems including brief information on power over ethernet (PoE) that is based on the available information at the time of writing the chapter.

Part 3 of the handbook, ‘Applications’, makes up the bulk of the publication and is broken into 22 chapters, as shown in Table 2. This includes a whole range of areas – many that are also covered in more detail in the separate SLL Lighting Guides – and four new chapters to provide a lighting design resource that is likely to encompass most ‘normal’ building requirements.

The new ‘Common building areas’ chapter includes the generic areas that are found in almost all types of buildings, such as entrance halls, corridors, lift lobbies, toilets, cleaners’ rooms and plant rooms. The guidance attempts to give practical information that has previously been absent in standards and guides. So, for example, toilets were previously simply designated as requiring 100 lux, with no specific guidance where this should be measured.

This chapter provides recommended lighting levels for the floor, basins and surrounding surfaces, at toilet seat level and over baby changing tables. Similarly, for example, there is increased granularity in the guidance for connecting spaces such as ramps, where it notes that for design purposes, they should be treated in the same way as corridors.

Applications

- Common building areas (new in 2018)

- Retail lighting

- Industrial premises

- Educational premises

- Retail premises

- Museums and art galleries

- Hospitals and healthcare buildings

- Places of worship

- Communal residential buildings

- Places of entertainment

- Courts and custodial buildings (new in 2018)

- Transport buildings

- Extreme environments (new in 2018)

- Exterior workplaces

- Exterior architectural lighting (new in 2018)

- Roads and urban spaces

- Security lighting

- Sports

- Historic buildings and spaces (new in 2018)

- Commissioning of lighting installations (new in 2018)

- Performance verification

- Maintenance

Table 1: The majority of the handbook provides a set of applications chapters that cover most ‘normal’ lighting applications

However, with an inclined floor and possibly flat areas, it notes that where ramps form part of an exit route, emergency lighting should be provided with additional emphasis on the start and stop of the incline.

Another example where the handbook drills down to essential, and practical, guidance is when describing the lighting needs for cleaners’ rooms that needs ‘to provide light on the sink, even when someone is leaning over it, and vertical illumination on any shelving’ to allow cleaners, for example, to safely select and then mix up chemical solutions for cleaning.

Ruffles has reflected that the more considered descriptions of the lighting needs of such spaces will be fed back to the European standards committees for potential inclusion in future codes.

‘Courts and custodial buildings’ is a new chapter that provides guidance on what lighting is required in these specialist spaces. It proved challenging to determine the technical provenance for some of the prevailing guidance.

For example, some existing court guidance gives maintained lighting levels of 125, 150 and 175 lux for, respectively, defendant’s toilet, child witness toilet and judge’s toilet. The handbook notes that the government department’s figures ‘appeared unusually precise and the rationale of why a judge needs 25 lux more in a toilet than a child witness is not explained’.

However, the key message was that these figures should be treated as a guide and, as with all design criteria, they should be discussed with the client during design.

The chapter includes commentary on the lighting requirements for practically all areas that make up courts and custodial buildings, and accounts for not only the aspects that directly have an impact on the visual environment, but also includes wellbeing, security and safety aspects for the inmate, custodial staff and visitors.

The latest version of the SLL Lighting Handbook

It notes the importance of lighting resilience, so there is no opportunity for complete failure, and that the electronic control system should not be susceptible to hacking.

A completely new chapter (currently being developed into a separate lighting guide) is ‘Extreme environments’, which provides contextual guidance on the environments as listed in Table 2. This chapter is a potpourri of environments that are likely to be read in conjunction with one or more of the specific application areas.

So, for example, the cold and freezing environments might be applied to applications as varied as an Antarctic research station, a distribution warehouse for frozen foods or a cold store in a local supermarket.

Similarly, explosive environments may be applied to disparate applications such as a flour mills, sawmill or laundry – where particulate matter in the air presents an explosion risk – as well as those spaces that contain unstable products, chemicals and gases.

The ‘Exterior architectural lighting’ environment is an area that has developed swiftly, spurred on by the versatility, controllability and ubiquity of LEDs, and so merits a dedicated new chapter in this rewrite of the handbook.

There is, however, far more to successfully designing and applying such lighting than simply determining the lamp type, and Ruffles writes about the demands of this specialist area in a separate article in this Lighting Supplement included with this issue of CIBSE Journal.

The brief new chapter ‘Historic buildings and spaces’ provides a commentary on the lighting of heritage spaces, considered in terms of four categories – historic building being converted to a new use; reuse of historic buildings and interiors; historic building preserved ‘as is’; and historic or sensitive exterior spaces.

The final category relates to spaces such as the gardens around a historic building, the streets in a world heritage city, bridges, ruins or areas of outstanding natural beauty. It notes that, as well as requiring special care in lighting design, the daytime appearance of the lighting infrastructure must also be carefully considered.

The remaining new chapter in the ‘Applications’ section is ‘Commissioning of lighting installations’, which makes an important debut in this edition of the handbook. Commissioning is often relegated in both time and resource, as the apparent active work necessarily takes place towards the tail end of many contracts.

However, as emphasised in this chapter, although a full commissioning management team may not always be appropriate for projects with relatively simple lighting installations, an appropriate level of commissioning management is always needed.

Extreme environments

- Cold and freezing environments

- Hot and humid environments

- Dusty environments

- Chemicals and chemical vapours

- Submersion: pools, ponds and water features

- Wash-down/clean rooms

- Marine (onshore, offshore and submersion)

- Vibration, impact and vandalism

- Explosive environments

Table 2: The new contextual sections on ‘Extreme environments’ are included as a chapter in Section 3 – Applications

The activities discussed clearly reinforce that the commissioning programme starts well before system installation, with appropriate pre-design assessments, and then runs continuously through to installation handover, development of operation and maintenance manuals, operator training, post-completion checks and adjustments, and seasonal inspections.

And finally, despite their status as appendices, the content of the three new final ‘chapters’ deliver abundant state-of-the-art information that is worthy of the lighter’s attention.

This includes an extremely well-considered and illustrated chapter on ‘Reflectance and colour’, that includes reference to the light reflectance value (LRV), for example on paint swatches in Figure 1, the current thinking on ‘Circadian lighting’, and a summary of the relevant ‘Building Regulations and environmental labelling schemes’.

The 2018 edition of the SLL Lighting Handbook is testament to the commitment and enthusiasm of a dedicated volunteer group of lighters, and provides a cornucopia of information produced by several different chapter authors.

Inevitably, there is crossover in information across the sections and chapters so, although the printed version is wonderful to flick through, it is very useful to download a digital version of the handbook (free to CIBSE members) so that it can be comprehensively searched with reader software when looking for information on specific topics that may appear in numerous locations.

References:

- SLL Lighting Handbook, Society of Light and Lighting, CIBSE, November 2018.

- Ruffles, P, SLL Lighting Handbook – www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZnvS3bcnA0 – accessed 10 November 2019.

© Tim Dwyer, 2019.

With thanks to Paul Ruffles for the material based on his presentation on the 2018 SLL Lighting Handbook, which can be viewed here.