In March 2020, the UK went into lockdown and employees were advised to work from home if possible, leaving all but essential premises empty. When we were let back out again, it was not long before the call to ‘go to work’ was reversed and office-based staff returned home again.

The shift has been significant: by April 2020, Office for National Statistics figures showed that 46.6% of those in employment (32.6 million people) were working from home, rising to 57.2% in London. In 2019, only 5% of employees were home workers.1

As a result, large commercial buildings are operating at a vastly reduced occupancy. For The Crown Estate, with a property portfolio that extends to five million square feet of office space in the West End, average occupancy had dropped to 10-15% by the end of August 2020.2

The buildings these people have left are designed to their capacity – a point that is particularly important when it comes to water systems. If left to stagnate, water becomes a breeding ground for bacteria, which can lead to pipe degradation and, crucially, Legionnaire’s disease. It is not enough to simply flush the taps through from time to time; maintenance regimes must be upheld, adjusted or increased to meet change of use.

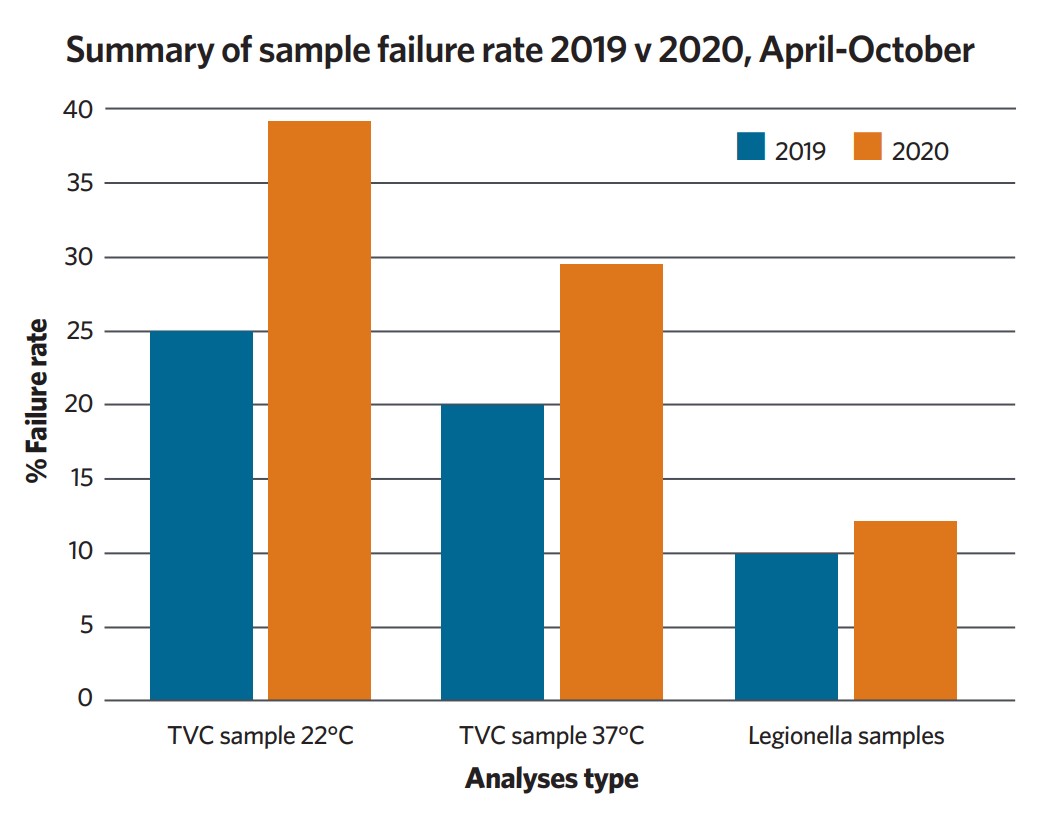

We analysed data from more than 30,000 samples from hot and cold water systems in buildings that were mostly following flushing regimes during the six months from April 2020. The data shows failure rates for total viable count (TVC), which gives an estimate of the total concentration of microorganisms in samples, have increased by almost 50% across the board compared with the same period in 2019. Positive legionella samples have risen by around 20%.

These results indicate that, while flushing helps prevent stagnation and legionella growth, overall microbiological control is likely to be compromised if it’s treated as a standalone solution. Deposits within the system – such as sludge buildup or biofilm caused by low use and stagnation – provide nutrients for harmful pathogens to grow, and lead to water-quality issues and system degradation. So what’s the solution?

First, assuming an unused building needs little or no maintenance is a mistake that is very likely to cost more in the long run. By laying the groundwork of good water-system management, major off-plan issues are less likely, the risk of a Legionnaire’s disease outbreak is reduced.

A legionella risk assessment should be reviewed after a significant change to a building’s use – an 80% or more drop in occupants is a significant change. Steps to prevent legionella include, reducing locations in which stagnant water can thrive by cutting tank capacity or the number of tanks in use. Cooling towers should be tested on a regular basis (at-least-weekly tasks are recommended in HSG274 Part 1). Site access should no longer be an issue for keeping up maintenance tasks.

There are also secondary disinfection solutions that ‘drip feed’ a system to control bacterial levels. Treated water, containing biocides such as chlorine and chlorine dioxide, is used to flush the system for a constant low-level defence that is far more effective than flushing alone.

Simply reopening a building without addressing water-system safety is not only irresponsible – it’s also potentially in breach of the law, according to the Legionella Control Association.3 Legionnaire’s disease causes similar symptoms to Covid-19, so preventing an outbreak is more pertinent than ever as we try to avoid the potentially life-threatening confusion of misdiagnosis (of either illness). When it comes to water-system maintenance, out of sight, out of mind is not an option.

www.gwtltd.com

WATER QUALITY INDICATORS

There are three types of sample generally used to indicate water quality

and that are key to public health:

■ TVC samples analysed at 22°C

■ TVC samples analysed at 37°C

■ Legionella samples.

TVC is a microbiological test that indicates the general level of contamination within a potable water system. It detects ‘viable’ microorganisms present in the sample, but doesn’t look at specific species.

Samples tested at 22°C will mimic growth of bacteria at ambient temperatures, whereas samples tested at 37°C are more indicative of bacteria that grows at body temperature, such as potentially deadly waterborne pathogens, including legionella.

References:

1 Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK labour market: 2019, ONS

2 ‘The Crown Estate says more workers returning to West End offices’, London Evening Standard, September 2020