Credit: iStock.com – Nobi_Prizue

Many HVAC system designers find that building automation and controls can be one of the most frustrating parts of a project. Often, there may be a last-minute push to get the details for the specifications, points list, sequences and diagrams completed before the project can go out to tender, and that means working with limited time, and without enough hours to put much effort into the design.

Working with the control contractor can be a challenge as well – from prices that exceed the budgeted amount to problems with the products, design and performance. After the project is complete, the owner may complain that the controls don’t seem to work in the way they expected. It seems like there has to be a better way to design and deliver controls.

The processes of designing, installing, programming, commissioning and operating control systems are complicated and fraught with problems. These range from a lack of training, to keeping up with new technology, and the complex process required to interpret design documents and deliver control systems. In many ways, we are fortunate to have projects that work as well as they do.

Is there a better way?

The challenges with the design and delivery of control systems are long-standing. Changes in codes and standards, and the need to have systems that provide improved energy efficiency and a healthy indoor environment, further exasperate these challenges.

Fortunately, these problems have not gone unnoticed. In the United States, efforts are now under way from ASHRAE and the US Department of Energy to improve the process and practice of controls design, delivery and documentation. Several of these programmes were highlighted in papers delivered at the joint virtual CIBSE ASHRAE Technical Symposium 2020, held in October.

ASHRAE Guideline 36

One of the most important efforts is coming from an ASHRAE committee, which has produced guidance based on research of the best-practice HVAC control systems. This project is titled High-performance sequences for HVAC systems.1

Guideline 36 defines best practices for efficient operation. A properly developed sequence can give significant efficiency improvements. The initial release, in 2018, focused on common airside systems, including single- and multiple-zone variable air volume (VAV). Current work is focused on expanding the guidance to include boiler and chiller plants. Over time, the effort will cover even more system types.

The guidance provides a detailed sequence for each system type, as well as copious notes for the designer. It accompanies ASHRAE Guideline 13, which focuses on how to write a controls specification.

Open building control

The US Department of Energy-funded Open Building Control project is intended to improve the process of controls design and delivery by developing tools and standards that will digitise the process – beginning with design through installation and verification.

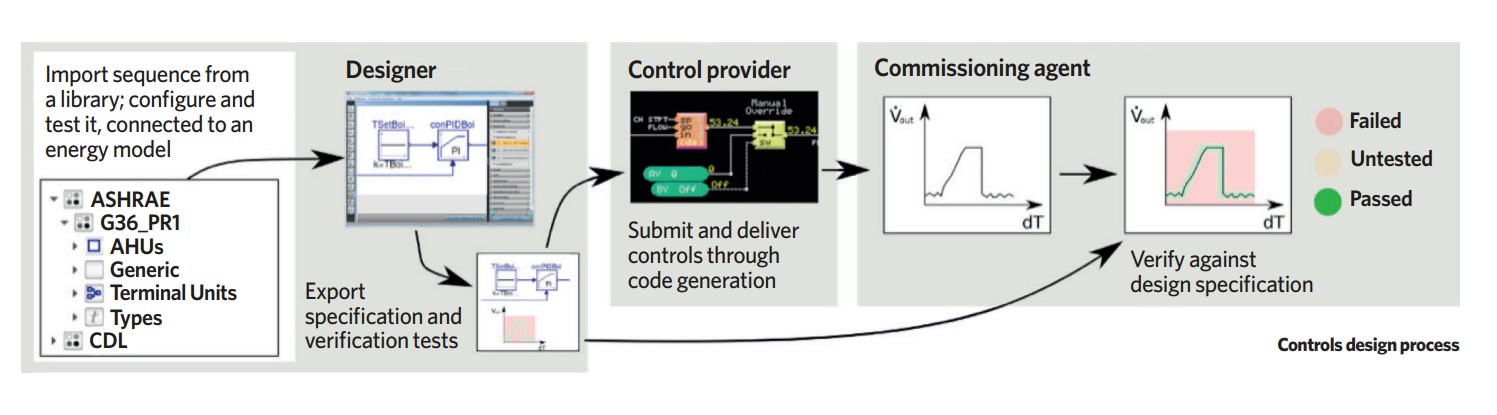

The idea is to start with new tools for the system designer that allow them to select from a library of high-performance control sequences – including those in Guideline 36 – or to develop their own sequences.

Sequences are developed using a graphical format in a control description language (CDL). The use of CDL allows for sequences to be tested during design and to be used as part of an energy simulation. Testing during design helps minimise the need to make changes during the construction and commissioning process. The CDL file is then included as part of the control design documents.

A properly developed sequence can provide significant efficiency improvements

The contractor can use this file to prepare their project estimates and complete submittals. When it is time to program the system, the CDL can be directly applied for use in the vendors controllers, or it can be translated for use in legacy products. Additional tools allow the contractor, owner, and commissioning agent to verify that the system is operating as designed.

Work on the Open Building Control project is under way at several of the US Department of Energy’s national laboratories and work has just started within ASHRAE to define the Control Description Language as an ASHRAE standard in Project 231P.

Controls co-design

In other industries, including the design of aircraft, automobiles and other complex systems, there has been a dramatic shift in how controls are designed. Instead of designing them toward the end of the design process, controls design is being done as a continuous and iterative part of the design process. This concept is called co-design and is the topic of a new US Department of Energy-funded project.2

There are many potential benefits to the co-design process, including reduced system costs through optimised system selection and reduced installation effort, as well as optimised efficiency and performance of the system during the design phase. However, it may also increase the time, cost and complexity of developing the system design. Use of the new tools and processes has the potential to lower these costs over time. Ideally, the additional value provided could be used to compensate the design team, while reducing overall projects costs for the owner.

Spawn of EnergyPlus

The final piece being funded by the US Department of Energy is the next generation of energy modelling tool EnergyPlus. The new version has a number of enhancements, including updated programming tools. It will also include the ability to more accurately model and simulate control sequences using a control-modelling open standard called Modelica. EnergyPlus is widely used in the research community and provides the back end for calculating loads in several widely used commercial energy modelling programs.

Summary

Used together, the programs described above have the potential to change the process for design and delivery of control systems dramatically. The process would begin with the concept of co-design – which means starting early in the process with models and other tools for the design of control systems. System designers would either develop their own control sequences using CDL, or select from libraries of pre-written sequences and tailor them to the needs of the building.

During the design process, the operation of the systems would be simulated, allowing for potential issues to be resolved at the design stage rather than during installation or checkout. The process flow then continues through installation and checkout, helping to eliminate much of the confusion and rework that exists in our current process. When the project is complete, the owner takes over not only the building and associated systems, but also gets a copy of the model and the simulation tools. This model is often called a digital twin and can be used for continued decision-making to optimise building performance.

About the author

Paul Ehrlich MASHRAE is founder and president of Building Intelligence Group

References:

1 ASHRAE Guidelines 13 and 36, www.ashrae.org

2 US Department of Energy Open Building Control obc.lbl.gov

3 US Department of Energy Co-Design Project, bit.ly/CJDec20PE1

4 US Department of Energy Spawn of Energy Plus, bit.ly/CJDec20PE2