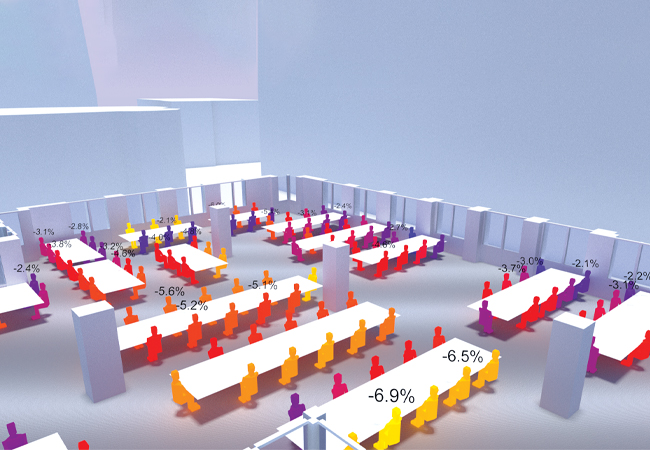

Cundall's Birmingham Office. The productivity mapping tool can be used to measure and optimise productivity

How do you make a business case for investing in workplace design to increase wellbeing to boost productivity? The winner of this year’s CIBSE Building Performance Awards Product or Innovation of the Year – Wellbeing was developed to address exactly this.

Multidisciplinary engineering consultancy Cundall has created a productivity mapping toolkit, which demonstrates how investing in workplace design can increase wellbeing and productivity and, ultimately, save on operating costs. It is estimated that 90% of business costs are associated with staff, so every small percentage improvement in productivity can equate to significant savings for businesses – a sum that could add up to hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of pounds, depending on the size of the organisation.

In developing its toolkit, Cundall explored a growing body of research (see panel, ‘Sources for Cundall’s wellbeing and productivity research’) that suggests workplace environments significantly affect productivity and office wellbeing. Studies from Harvard and Oxford Brookes universities, for example, estimate a 20% impact on productivity based on a range of environmental factors. Quantifying and calculating the impact of such environmental changes is at the toolkit’s core.

Productivity boost

The toolkit was praised by the awards judges for the ‘effective way it demonstrates to clients the impact of wellbeing’. Cundall’s productivity mapping tool, which quantifies elements of the indoor environmental quality (IEQ) – such as temperature, CO2 levels and daylight – can be used to measure and optimise employee productivity in existing workplaces, as well as in the design stage of new buildings.

The company used the latest academic and industry research to produce a bespoke parametric modelling tool that shows where occupant performance metrics are linked with the environmental parameters of thermal comfort, CO2 and daylighting at each desk position across a floor plate on an hourly basis. The tool can identify areas in a building where the IEQ is likely to reduce levels of occupant productivity. It can then be used to optimise architectural test fits of options to improve productivity.

Cundall says the toolkit can predict the loss of productivity at any workstation and assess the benefit of remedial measures. It can also aggregate the loss of productivity, which, when combined with an organisation’s revenue or the salary of the occupier, can give an assessment of the financial impact for a range of measures. When linked with the capital costs, it can be used to demonstrate the financial return on investment and payback of each proposed intervention.

Demonstration

The drive for healthier workplaces predates the Covid-19 pandemic. Increased understanding of the link between healthy environments and productivity was developing alongside advances in environmental simulation and monitoring tools that enable engineers to assess IEQ at design stage and once buildings are occupied. While improved monitoring and research may have spotlighted the link, however, Cundall recognised the difficulty in demonstrating this in financial terms to occupiers and investors.

Improving productivity by even 1% or 2% can indicate significant savings – which can be measured in hundreds of thousands of pounds, with a payback of months or weeks

Simon Wyatt is the sustainability partner at Cundall, responsible for the delivery of the firm’s health and wellbeing offering. He explains: ‘We started on a journey into health and wellbeing around six years ago, when we applied the Well Building Standard to our office fit-out in London – we were the first people in Europe to achieve certification using that standard. Off the back of that, we started to do quite a lot of work in health and wellbeing. As engineers, we got interested in the details, the measurement and verification side – the fact that it was based on actual performance rather than design performance; actually achieving measured results.’

After several presentations by Cundall on this subject at conferences and in CPDs, one question kept coming up: how much does it cost, and what is the business case associated with designing for wellbeing? This prompted the team to look at a review process that would enable them to demonstrate return on investment to a client, in a similar way they would for energy-saving assessments.

‘At the time, organisations such as the British Council for Offices were putting out reports and studies into the effects of occupant wellbeing on productivity,’ says Wyatt. ‘So, we carried out a review of the academic literature around it.’

Cundall explored a plethora of studies linking wellbeing and IEQ. ‘We were confident we could accurately assess IEQ, whether monitoring it in existing buildings or using environmental simulation tools to predict it for new buildings,’ Wyatt says. ‘We use IEQ parameters – such as temperature, relative humidity and light levels – which can be monitored and measured on a minute-by-minute basis.

‘For new buildings, we use standard industry simulation tools, such as Radiance for daylighting, and IES, TAS and EnergyPlus for thermal comfort and thermal parameters, and we use sensors to sample CO2 concentrations and air quality. We then process the IEQ data using the bespoke parametric tool we developed, and convert that into statistical average productivity gain.’

Live feedback loops can also give occupants the information to improve their environments, and help with fine-tuning a building post-occupancy. The toolkit could also be used for organisations selecting potential buildings to lease, as part of a due diligence process, to estimate the likely impact the floor plate of a particular building will have on employee performance and productivity.

Marginal gains

Cundall’s literature review took in more than 100 academic papers and other research, with the team honing them down to around 16 (see texts in panel), and drawing on particular ones to combine and consolidate the relationship between IEQ and productivity for its model. While studies from Harvard and Oxford Brookes universities have indicated an impact of up to 20% on productivity from environmental factors, Wyatt says Cundall was more cautious in attributing such large potential impacts when refining its toolkit.

Stimulation of occupant access to daylight linked to productivity loss

‘Some academics and industry figures are sceptical about claims linking IEQ, wellbeing and productivity, especially when it comes to CO2 levels, and we were circumspect about some of the more headline-grabbing claims about improvements to cognitive performance,’ Wyatt says. ‘The toolkit was developed by me and Ed Wealand – head of the CIBSE Air Quality Group – and we had data scientists and data engineers building the tool, going through the studies and making the links.’

The tool takes a conservative approach to estimating potential wellbeing productivity gains from improving environmental factors, says Wyatt. ‘We’re only estimating very marginal gains for all these things, but these are significant because we’re talking about the productivity of people – and, for most organisations, that’s 90% of their costs. Improving productivity by even 1% or 2% can indicate significant savings, which can be measured in hundreds of thousands of pounds, with a payback of months, or even weeks. So, you don’t need a 20% forecast saving to make a compelling business case.’

Cundall achieved Well Building Standard certification for its London office fit-out

Cundall is looking to enhance the toolkit, when possible, by incorporating the impacts of acoustic treatment, HVAC system types, and the effectiveness of air distribution and internal pollutants.

Model workers

Measuring and modelling environmental factors in a building is within the technical capability of engineers, but productivity is more challenging.

‘If you go into an organisation and try to measure an individual’s productivity based on the space, you’ll never get it, because productivity is affected by many variables. It’s impossible to isolate the critical factor,’ Wyatt says.

‘We did some CO2 cognitive performance testing in our offices, for example, by changing ventilation rates, but we couldn’t get consistent results because, obviously, there were intangibles such as how people were feeling that day, their emotional state, whether they were feeling stressed.

‘But the academic studies we looked at are done on such a large group that they are able to establish statistical averages. So, all of the tools and the assessments we’re doing aren’t looking at specific individuals – statistically, that space is realigned or interventions are made to deliver a better result. The person sitting at that workspace is statistically more likely to be slightly more productive by removing some of the frictional negative experiences they feel.’

The most effective deployment of the tool so far has been in live environments, Wyatt adds, where quantitative monitoring over time, using sensors, has been combined with qualitative studies, such as building use studies and occupancy surveys. Getting feedback from occupants on how the building environment affects their perception of wellbeing and productivity can inform interventions, and help build a business case for modifications in areas such as ventilation and lighting.

Cundall’s Birmingham Office

Although objective improvements in IEQ have correlated to greater feelings of wellbeing in survey participants, Wyatt accepts that part of the perception of occupants that their productivity has improved may be down to other factors – including a ‘placebo effect’. Simply being seen to take action can boost feelings of wellbeing. ‘Studies indicate that, if people feel they are being listened to, their feeling of wellbeing increases and, generally, their productivity is expected to rise. We have seen such responses from just installing sensors before interventions.’

Pandemic impact

The Covid-19 pandemic may have brought into focus issues surrounding IEQ of buildings and ventilation, but the lockdown and widespread closure of offices in the UK means there has been limited interest in the productivity mapping element of the toolkit.

However, Wyatt says there has been a big increase in interest in improving IEQ, particularly with the reopening of many workplaces imminent. ‘We’re seeing a lot of sensors being installed at the moment, and an increasing demand [from businesses] for certification and badges to verify their commitment to IEQ and employee wellbeing in buildings,’ he says. ‘A number of landlords are using our services as a way of encouraging people back into the office.’ CJ