An interior of a retrofitted home in Yangon, Myanmar. Credit Kerstin Duell

Doh Eain is a social enterprise that has been operating in Yangon, Myanmar, since 2017, against the backdrop of opening up the country, and a rise in investment and social mobility. Our vision for the organisation is to support communities and individuals through the restoration of heritage properties and the renewal of public spaces.

Myanmar, today, is at a point of significant challenge. Covid-19 and the February military coup have had a significant impact on the population, and 25 million people – nearly 50% of the population – are predicted to be living below the national poverty line by 2022.1 The World Bank is reporting that gross domestic product will be at -18% for 2021.

Yangon is a city abundant in heritage buildings. It developed through colonial dominance during the 19th century and, by the early 20th century, was a thriving trading hub. Alongside British colonial architecture, the city boasts mansions, warehouses, public offices and religious buildings built by Gujarati Indians, Baghdadi Jews, Arab Muslims, Christian Armenians, and Chinese people – resulting in an eclectic, diverse and densely built cultural heritage.

In 2005, government administrative functions were relocated to the new capital, Naypyidaw, leaving many large public buildings in Yangon without function and to deteriorate in the challenging monsoon climate and the hot, intense dry season. Some public buildings were reappropriated as housing, either officially or by squatters, and many were left abandoned.

Simple interventions can make a big difference to residential properties

This neglect continues to be a significant loss to the city and includes not just public buildings, but also a vast number of privately-owned residential buildings.

It is these buildings that are so characteristic for the historic streetscape in the city centre: 70% of its 6,000 historic buildings are residential.

In Yangon, these residential heritage properties are often inherited, and there is limited family means to maintain them. Private owners of heritage properties struggle to find the resources, expertise or finance to look after their homes, even for very minor interventions and maintenance.

Doh Eain provides design, construction and financing support, connecting owners with tenants and then managing the property while it is rented out. (See panel, ‘How Doh Eain finances building restorations’.)

One aim is to protect Yangon’s cultural built heritage, but equally important is the objective to develop a sustainable approach that provides good-quality homes and income for owners, who are often from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

We restore buildings and adapt them to make them safe, resilient and healthy spaces. The interventions that we, at Doh Eain, make are relatively simple: managing airtightness for air conditioning performance while maximising the impact of passive ventilation wherever possible (to make it a viable choice for residents); keeping large volumes; restoring openings for cross-ventilation; and reinstating or repairing overhangs and other shading devices.

How Doh Eain finances retrofitting

Doh Eain pays for the restorations of heritage properties and, in return, manages the properties after renovation on a short-term basis (five-10 years). Once costs are recovered, use of the properties is returned to the owners, who may elect to continue with Doh Eain’s management services. When a contract is fulfilled, investors stand to receive internal rates of return of 15% up to 30%, or even higher. So far, early lenders to Doh Eain have received an annual interest rate of 5%.

●For a Cultural Heritage Finance Alliance case study on Doh Eain visit here and for its white paper Impact and Identity: Investing in Heritage for Sustainable Development visit here

In Yangon, the heritage vernacular (typically) is to render the building externally to protect it from the driving, intense, monsoon rains. Internally, we expose brickwork or add a lime render to allow the walls to breathe.

Modern services and appliances are installed – there are many challenges with water supply and electricity, so automating these services makes them efficient and user-friendly. We also now add double-glazing in our renovations. While this is an established staple globally, it is a challenging product to find in Myanmar because of import regulations. However, with the opening up of the country over the past 10 years there are now options on the market, and some manufacturers exist locally.

The interventions described here are very simple, and certainly not high-tech, but although such renovations can be low-cost from an international standpoint, they are still exorbitantly pricey for low-income homeowners. In addition, typical local owners of heritage buildings do not have access to the heritage or conservation knowledge, skilled craftsmen or finance to make such renovations to their properties.

We advocate for the protection of heritage buildings, but we also advocate for quality restorations to create climate-resilient homes. As part of this advocacy, we carried out a research project – with Statement architects and Beca engineers – to model the impact of the renovations we undertake within Doh Eain, and to better understand the local climate, the challenging weather, and its impact on building performance and thermal comfort for residents.

Yangon has an eclectic and diverse mix of heritage buildings

We were able to demonstrate that, by making these simple alterations to buildings, they perform better, reduce lifetime costs for energy consumption, and create a healthy environment.

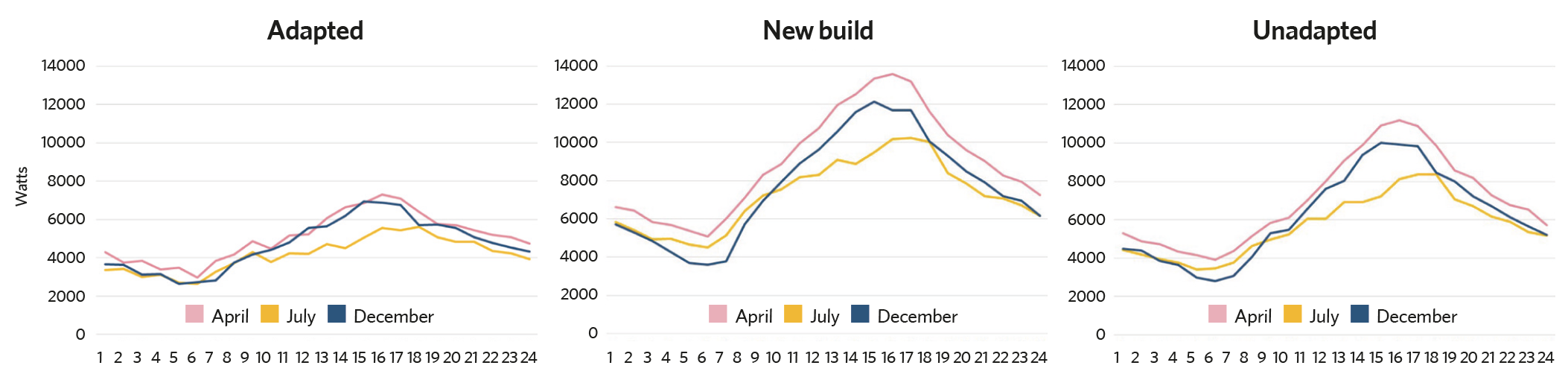

Through the research, we analysed three building typologies: an unadapted heritage building (the vast majority of homes across downtown Yangon); an apartment that had gone through a typical adaptation by Doh Eain; and a new build that would be in line with the Myanmar National Building Code (see panel, ‘Modelling of interventions’).

The national code currently has minimal requirement for reduced energy consumption, despite advocacy from the Myanmar Green Building Society. New residential buildings are typically single-skin, concrete-block infill walls and single glazed. In this context, it was relatively simple to model the three typologies to demonstrate the positive impact that simple alterations can make.

One key finding from the research was the impact that the monsoon season has on building performance. In line with theory, the small diurnal temperature range – the variance between daytime temperature and night-time temperature – in the ‘summer’ (monsoon season) showed that thermal mass had the least effect on performance during this season.

Modelling of interventions

The modelling of unadapted, adapted and new buildings was carried out using E20 Hourly Analysis Software by Carrier, also known as HAP51. The modelling showed the impact the building fabric has on the demand for energy consumption from cooling load to maintain a steady internal temperature at 24°C (with a 1K buffer).

Data inputted was: material data, occupancy, weather data, air-change rates and electrical loads.

The weather data provided temperature profiles for three selected days, which represented the peak days for the months of April, July and December.

For July (monsoon) the energy load range is very low for ‘adapted’. This difference to ‘unadapted’ suggests that it is not the similarities in construction such as thermal mass, which is affecting this difference, but is a result of the additional interventions of insulation and double-glazing.

Modelling shows the energy use of the adapted buildings with insulation and double-glazing is lower than that for new-build and unadapted properties

No lag time was seen for the adapted building in July and the total energy use was still lower than the unadapted building, both of which are thermally massive. This proved that the additional interventions of insulation and double glazing were the key elements affecting the reduced energy consumption.

The quality of the environments we inhabit are essential for our health, mental health and wellbeing. We now feel this more acutely thanks to the lockdowns and stay-at-home orders we have experienced over the past 18 months. Making small interventions to improve these environments is important, and not just for the money they can save on energy bills.

Combining this with a broader social impact is important at Doh Eain. Our work offers a wider reach to communities and neighbourhoods by supporting the renewal of public spaces through our participatory design approach and community engagement focus.

Access to public space is another core element of improved wellbeing that has been proven during the global pandemic and seen around the world. Millions of people do not have access to private outside space, so public spaces become essential for socialising, having a place to rest, exercise, and play.

Yangon fares poorly in its provision, with just 0.32m2 of public space per person. Jakarta has 6m2, Bangkok 8.5m2 and Paris 30m2.

Covid-19 and the military coup have driven us to review what we can and should be doing. Our core areas of focus within Doh Eain – protecting heritage, improving buildings, supporting communities and improving access to public space – are now all the more important in the ‘new normal’.

Don Eain has transformed a number of Yangon's 'trash alleys' into green community spaces. Credit Kerstin Duell

One challenge is to reopen the alley gardens, which have been closed to the public because of Covid and the coup, further restricting the already limited outdoor space that exists within neighbourhoods.

We are investigating opportunities for taking our approach to new countries including Georgia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and India. We are particularly excited about Georgia as we see many of the same opportunities and challenges we had in Myanmar.

Global trends are changing; people do not need to be bound by a single location. There is significant growth in environmental and socially conscious travel, as well as lifestyles, and the tech industry is growing – particularly in Asia – unlocking new opportunities to reach and serve building owners, tenants, guests, investors, and neighbourhoods.

The impact of supporting owners of privately owned heritage in new areas would be significant. Funding often exists for public heritage buildings, but support to low-income owners is overlooked. The value of the cultural and social impact of these buildings is also overlooked, as is the cost to the climate of demolishing and replacing them.

Using digital tools, we aim to support homeowners and build a community, providing the services to support them and which can connect them to socially conscious renters, travellers and social-impact investors – enabling the protection of heritage, good quality environments, and resilient neighbourhoods for more communities.

About the author

Beverley Salmon is deputy director at Doh Eain

References:

1 Covid-19, coup d’etat and poverty: compounding negative shocks and their impact on human development in Myanmar, UN Development Programme, April 2021,