Lighting design is going through a small revolution. The volume of the space is taking on as much importance as lighting the visual task, and the latest version of the most influential lighting guide in this area, EN 12464-1 Light and lighting – Lighting of workplaces, is reflecting these changing times. Adopted into national standards in the UK in the autumn, as BS EN 12464-1:2021, this latest version appears a decade after the last revision. So, what are the key updates?

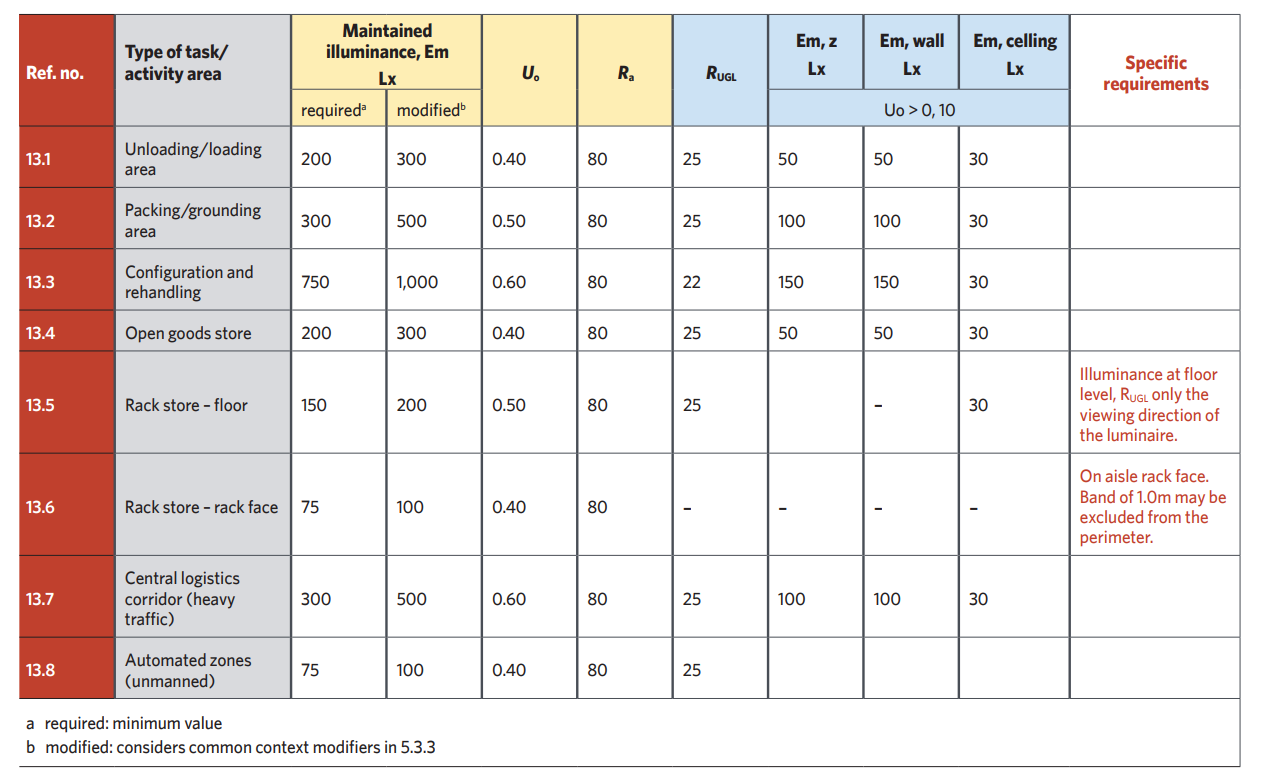

The most obvious changes are to be found in the revised tables in Chapter 7 – the list of specific lighting requirements. Here, there is a changed layout and additional considerations. As well as the previously required illuminance, which specifies the lowest maintained value in the activity area, there is now an additional, higher modified value, and requirements for mean cylindrical illuminance, walls and ceilings are specifically listed in the tables.

The modified value enables the illuminance to be adapted to real tasks and activities. The aim is to create optimum visual performance and avoid errors at work by considering varying factors, including the age of the user. Increases in light levels refer to the scale of illuminance in EN 12665, which are levels at which the average person can detect visible change.

In a brightly lit area, large changes in values are needed; in a dimly lit area, people can already perceive much smaller changes. These are not maximum and minimum values, however; rather, they are ranges to be considered.

Increased illuminance is required if:

- The visual task is critical to the workflow

- The correction of errors is costly

- Accuracy, higher productivity, or increased concentration are important

- The task is small or of low contrast

- The task is performed for an unusually long time

- The area has little daylight

- An employee’s eyesight is below the usual level of vision.

If there are one to two additional requirements, an increase of one level should be made – for example, from 500 lux to 750 lux. More than two additional requirements leads to an increase of two levels. Where the visual task requirements are lower, however, it is possible to reduce illuminance by one level, but this is a rarity.

This change gives the lighting designer the ability to tailor the lighting to the actual needs of the user, and to make it more adaptable. The use of lighting control is, therefore, recommended: dimming means the luminous flux of a luminaire can be adjusted individually, defined lighting scenes used, daylight considered efficiently, and variation of colour temperature added.

Quality criteria are now integrated into the tables for wall, ceiling and cylindrical illuminance, and are intended to provide greater safety and enhance the ambience of the room. For good visual communication and recognition of objects, vertical and cylindrical illuminance levels of between 50 lux and 150 lux are required, depending on the activity.

The recommendation to set the illuminance up to two levels higher than the required maintained value will be controversial

To avoid the impression of gloominess, and to increase adaptation and wellbeing, it is desirable to use bright room surfaces. So, in addition to the new illuminance levels on walls and ceilings, there are recommendations for reflectance levels. Up to 90% is now recommended for ceilings, and 60% for floors. Glazing with a reflection factor of 10% is also recommended, and even the reflectance of important objects – such as furniture and machines – should be considered. Although a project may still be in the planning stage, all reflectances should be recorded as accurately as possible.

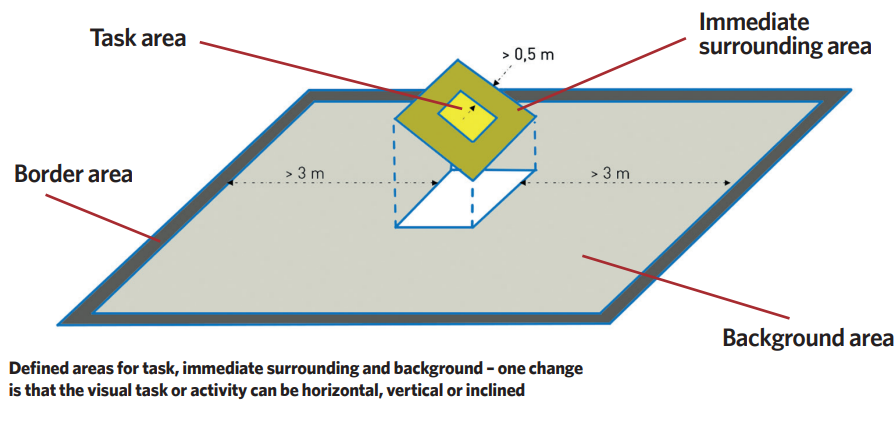

Illuminance is still targeted to where it is needed, using the defined areas of task, surrounding area and background area. One change is that the visual task or activity can be horizontal, vertical or inclined. Once the area is defined, the requirements – levels, uniformity, glare limitation, and so on – can be taken from the application tables of the standard. For some applications, the new standard contains changed specifications – for example, the increase in illuminance from 300 lux to 500 lux for general activities in classrooms.

For areas where different tasks are performed, the most stringent requirements must be used. The modifiers are then used to calculate the appropriate illuminance value for the actual working condition. Once this maintained value is calculated, the illuminance levels for the immediate surrounding and background areas are then selected.

Tables such as the one above on warehouse lighting have been expanded to include a higher modified illuminance and specific levels for cylindrical (EM z), wall and ceiling illuminance

There is a change in the border area. To simplify uniformity calculations, points within a band next to the wall can be excluded from the calculation, unless the area of the visual task lies within this boundary area. The introduction of this band allows for a more efficient and cost-effective lighting system. Its width is set at 15% of the smallest dimension of the area under consideration or 0.5m, whichever is the smaller.

If higher maintained illuminance values have been selected, the wall, ceiling and cylindrical illuminance values should also be increased by the same number of steps on the scale of illuminance. The recommendation to set the illuminance up to two levels higher than the required maintained value will be controversial, but then this is covered by the standard, which says that dimmable lighting should be used to ensure levels are met during varying hours of operation. We need to emphasise what electricity is consumed, rather than the installed load, for this to become accepted though.

Glare

Glare is the unpleasant sensation caused by bright surfaces in the visual field – such as illuminated surfaces, parts of light sources, windows and skylights – and can be psychological or physiological. To select a luminaire suitable for the lighting installation in a particular room, the rating of the psychological glare emanating directly from the fitting must be calculated according to the CIE unified glare rating (UGR) table method. In addition, a new informative annex to the standard describes the recommended procedure for the application of UGR in ‘unusual’ situations. There are further details on the procedure – for example, for unusual luminaire sizes, irregular surface shapes and arrangements of fittings – as well as deviating degrees of room reflection.

Key changes

- Differentiated illuminance

- Visual and non-visual effects of light

- Walls, ceilings and cylindrical illuminances

- Design considerations

- Task, surround and background area

- Glare requirements

- Flicker and stroboscopic effects

- Example requirements of different applications

- Requirements for railway installations

Flicker and stroboscopic effects (also referred to as temporal lighting artefacts, or TLA) can lead not only to reduced visual comfort and work performance, but also to physiological effects, such as fatigue and headaches. So, lighting systems should be designed to avoid the negative effects of flicker and stroboscopic effects throughout the dimming range. Flicker is described by using the IEC short-time flicker indicator (PstLM). Flicker can be perceived by the eye at a frequency below 80Hz. Stroboscopic effects can be objectively quantified with the stroboscopic visibility measure (SVM) method. A PstLM of 1 and an SVM of 0.9 should not be exceeded. From 2023, the SVM limit will be cut to 0.4.

Toranomon Hills Business Tower, Tokyo, Japan, by Sirius Lighting Office, winner of the Radiance Award at the 2021 International Association of Lighting Designers Awards: the volume of the space continues to take on more importance, with an emphasis on lighting vertical surfaces and objects

BS EN 12464-1:2021 refers to the European Ecodesign Directive, in which the limit values for lamps operated directly on mains voltage are specified. This currently affects retrofit lamps in particular – details can be found in the directive – but beware: in the next stage, these specifications could also apply to LED luminaires. Discussions on this are underway.

Other practical approaches and methods are presented in the appendices, which describe the room brightness and detection of objects and people. In Appendix B, there is additional information on visual and non-visual effects of light. It notes that light is not only essential for vision, but also produces biological, non-visual and emotional effects that are important for human performance, wellbeing and health. However, current lighting practices, and the demand for energy conservation, tend to reduce illuminance. This can create conditions that are not conducive to human wellbeing and visual performance.

The importance of darkness and daylight rhythms – especially before, after and during bedtime – are also described, and it is noted that changes in the distribution of the light spectrum at different times of the day can be helpful to stabilise circadian rhythms. The non-visual effects depend on the amount and time of exposure, spectral power distribution, exposure duration and personal parameters, such as circadian rhythms. These goals can be achieved with daylight and electric lighting.

The appendices give examples of lighting designs for an open-plan office, an industrial workshop, and a manufacturing area. Starting from the basic requirements of the tables, the individual requirements are analysed step by step, which can lead to modified maintenance values of the different areas.

This is a brief overview of the main revisions to what may be the most important standard for lighting designers. There are some welcome changes, which start to make an adjustment away from lighting engineering to lighting design in its fullest sense.

- Helen Loomes FSLL, of the Trilux Akademie, is vice-president of the Society for Light and Lighting.

- BS EN12464-1 Light and lighting – lighting of workplaces, published in August 2021, is available at shop.bsigroup.com

- Material source: Trilux Akademie. For more on the standard, visit www.trilux.com/e-learning/register and enter the code ‘Academy’ to get to the registration page.