There has been much clamour in recent months about the poor state of school ventilation and the need for investment in air cleaners for classrooms1 – but is ventilation in schools poor?

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been growing recognition of the importance of virus carried in exhaled breath in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.2 Virus shed in the respiratory system of an infected individual become encapsulated in droplets of respiratory fluid.

These droplets have a continuum of sizes (and, therefore, volume of fluid) ranging

from <1μm to 100μm-plus. Once exhaled, they can decrease in size because of evaporation, and the smallest droplets (sub 5μm) – often termed aerosols – can remain airborne for hours, building up in poorly ventilated indoor spaces.

Over time, the concentration of viable virus in the air of a room containing an infector will reach a steady state. The poorer the ventilation, the greater the steady-state concentration of virus in the air.

Are schools poorly ventilated?

The importance of ventilation in providing suitable air quality for comfort, concentration and health has long been understood. Before the early 20th century,3 the only way to provide outside air was by natural means – exploiting the natural forces to encourage outside air in and exhausting contaminated air out. This principle has remained popular for UK classrooms and most schools have a natural ventilation strategy, although mechanical and mixed-mode ventilation are becoming more popular – especially in newer schools.

Classes noted as poorly ventilated in winter are assessed as well ventilated in summer, despite the design strategy being the same

Most natural ventilation designs require the opening of a vent, usually a window, to provide a means of incoming and exhaust air. This can create issues with cold draughts in the winter and often – because of a lack of occupant understanding of the ventilation strategy – results in vents being kept shut. The resulting lack of ventilation leads to a build up of exhaled breath, bio-effluents, off-gassing pollutants from furnishings, and pathogens, leading to a less healthy environment, which has been shown to affect pupil concentration and cognitive ability.4 Perhaps this has led to the notion that classrooms are poorly ventilated?

Before Covid-19, much research into school indoor air quality (IAQ) concluded that, in the main, poorly ventilated classrooms are the result of a lack of occupant interaction with the ventilation design strategy rather than a sub-optimal strategy.5

Often, classes noted as being poorly ventilated in winter are assessed as being well ventilated in summer, despite the design strategy remaining the same.6 Indeed, if we are to say that most school classrooms are poorly ventilated, it would suggest that the many architects, engineers, contractors and building control personnel involved in the design and build of schools for more than a century have failed to consider this important aspect of building design.

As well as providing adequate IAQ, ventilation is often used to cool classrooms. Typically, the flowrates required to provide ventilative cooling are larger than the flowrates required for IAQ. As such, there should be the capacity within the ventilation design to provide adequate IAQ during the heating season.

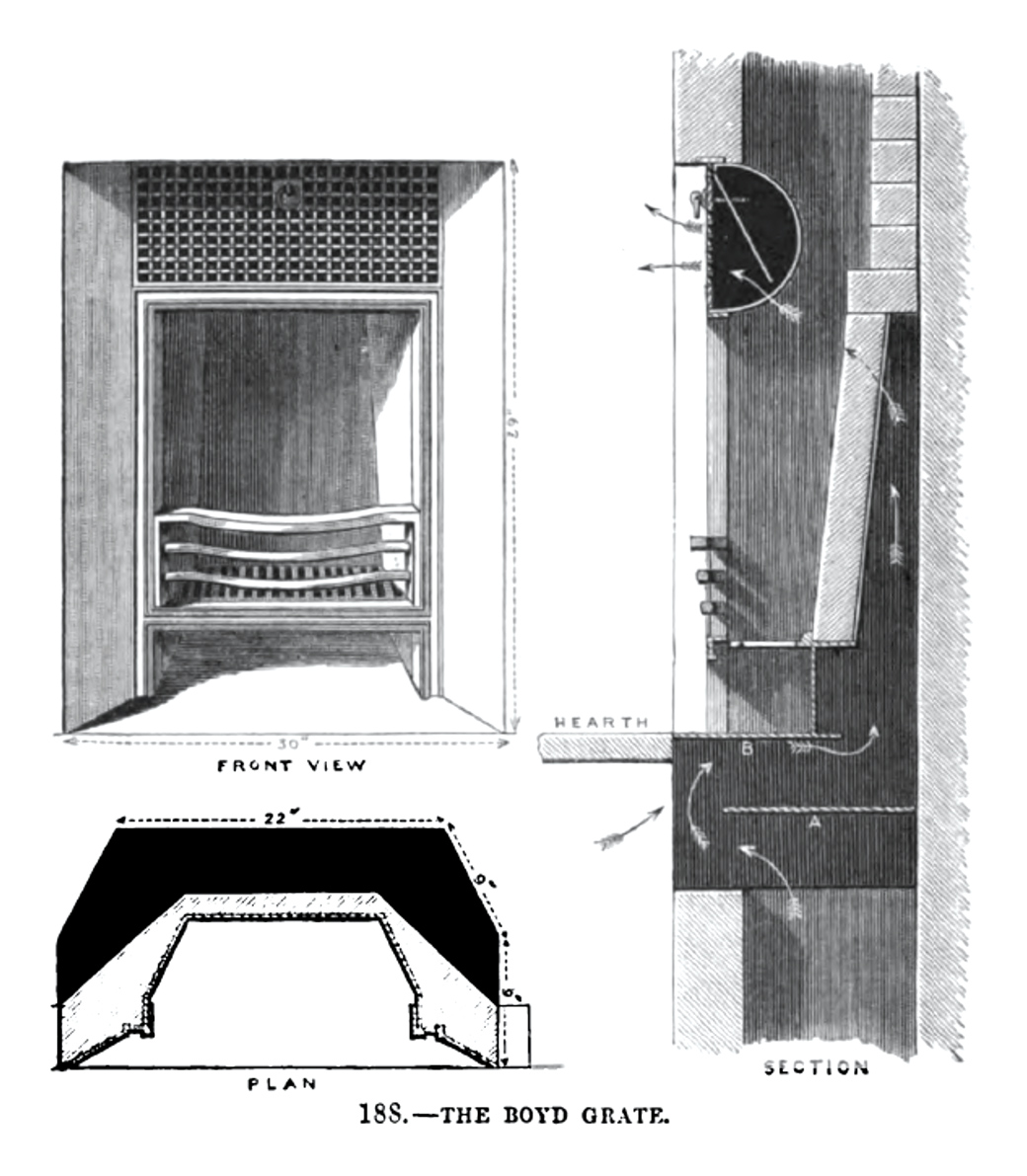

How can we balance ventilation provision with occupant comfort? This is not a new problem. See Figure 1 for a Victorian solution for tempering incoming air. Another strategy was pre-heating incoming air and using heat sources under windows, creating a plume of hot air that mixes with incoming, cooler outside air. However, this method resulted in heat escaping out of the window.

Figure 1: Tempering incoming air was school design guidance in the 1870s. Here is an example of outside air being drawn behind the back plate of an open fire (A-B) and pre-heated before being drawn into the classroom through a decorative grille (Ref: Robert Robson)

In recent decades, there has been a drive to improve the energy efficiency of classrooms, with more airtight rooms to prevent the continuous flow of outside air through cracks. In older classrooms, these adventitious draughts have provided some background ventilation, but in newer buildings, it has become even more important to get the ventilation design strategy right.

For more than a decade, guidance for new-build schools has requested that the supply of outside air be delivered in a way that does not result in draughts. In 2018, the school ventilation design guide BB 1017 set out a non-statutory design framework for the delivery of outside air year round. This has led to several innovations for classroom ventilation that use heat generated in the classroom from occupants, lighting, computers, and so on to pre-warm incoming air – reducing the need for additional space heating while delivering comfortable ventilation.

As there are many thousands of school buildings in the UK, it is inevitable that there will be some poorly ventilated classrooms. These may have arisen because of modifications to spaces, changes of use, changes to ventilation provision – for example, the addition of window-opening restrictors – or systems in need of repair.

The provision of CO2 monitors to schools should help them identify poorly ventilated classrooms and undertake remedial works to bring it up to standard. In those spaces where ventilation provision cannot be solved in the short term, consideration should be given to air cleaning technologies until an appropriate solution can be implemented (see CIBSE’s Air cleaning technologies).

Future classroom design

Ventilation should not be considered in isolation. If we focus building design solutions on the health and wellbeing of occupants, we must consider all aspects of design, including energy efficiency, ventilation, lighting, and acoustics (see CIBSE TM40 Health and wellbeing in building services). The golden thread of design intent of the holistic design also needs to remain unbroken from concept through to construction completion.

The Department for Education’s Building Bulletin design guides are useful. Where guidance is non-statutory, designers should ensure clients and building users understand the benefits of adhering to the guidance notes to produce the best indoor environments for the life of the building.

Educating occupants about how to use their building to get optimal performance from these designs will remain a challenge. CJ

- DR Chris Iddon MCIBSE is the chair of the CIBSE Natural Ventilation Group

REFERENCES

- England could fit Covid air filters to all classrooms for half cost of royal yacht, The Guardian, December 2021, bit.ly/CJApr22CI2.

- Covid-19: epidemiology, virology and clinical features, UK Health Security Agency, updated 6 October.

- Robson, ER, 1874, School architecture: being practical remarks on the planning, designing, building and furnishing of school-houses.

- The relationships between classroom air quality and children’s performance in school, Building and Environment, April 2020, bit.ly/CJApr22CI3.

- IAQ in naturally-ventilated primary schools in the UK: Occupant-related factors, Building and Environment, August 2020, bit.ly/CJApr22CI4.

- Iddon, CR, Huddleston, N, Poor indoor air quality measured in UK classrooms, increasing the risk of reduced pupil academic performance and health. In Proceedings of the International Indoor Air Conference, Hong Kong, China, 7–12 July 2014.

- BB 101: Ventilation, thermal comfort and indoor air quality 2018, gov.uk bit.ly/CJApr22CI5