The CIBSE ASHRAE liaison committee supported a seminar at the 2023 ASHRAE Winter Conference in Atlanta, titled ‘Accelerating change in building design and operation towards a decarbonised and net zero energy future’. It considered a cross-section of skills, tools, systems and methods that are driving buildings towards net zero. Two of the presentations touched on a common theme and are briefly reported in this article.

Adrian Catchpole, CIBSE President-elect, spoke on how the application of contemporary tools and emerging technologies may be used to deliver energy efficient, environmentally responsible projects.

He argued that the key starting point was to ensure a clear direction in the brief, and – although ‘not rocket science’ – it might require the design team to take the client ‘on the journey’.

The whole team needs to carefully consider and discuss desired project outcomes, and establish clear success factors that can be used to measure key work stages to ensure the project is delivered effectively.

The monitoring of key outcomes can feed a collaborative process of feedback and continuous improvement throughout the whole life of the project.

When the goals have been defined properly, the dynamic simulation model begins to emerge – a developing 3D representation of the building that reflects shape, form and hygrothermal characteristics, providing the core model, preferably based on a common date environment (CDE). The model can be used to run numerous simulations, optimisations, daylight modelling, overheating assessments, compliance checks, systems evaluations, life-cycle evaluations, and so on.

Catchpole said the model should underpin the whole life of the project and then move onto the client’s asset team for commissioning, post-occupancy operation, and maintenance. He noted that, typically, a concluding simulation by the design team would provide a prediction of energy use in operation, based on the final building and systems, as represented by the model.

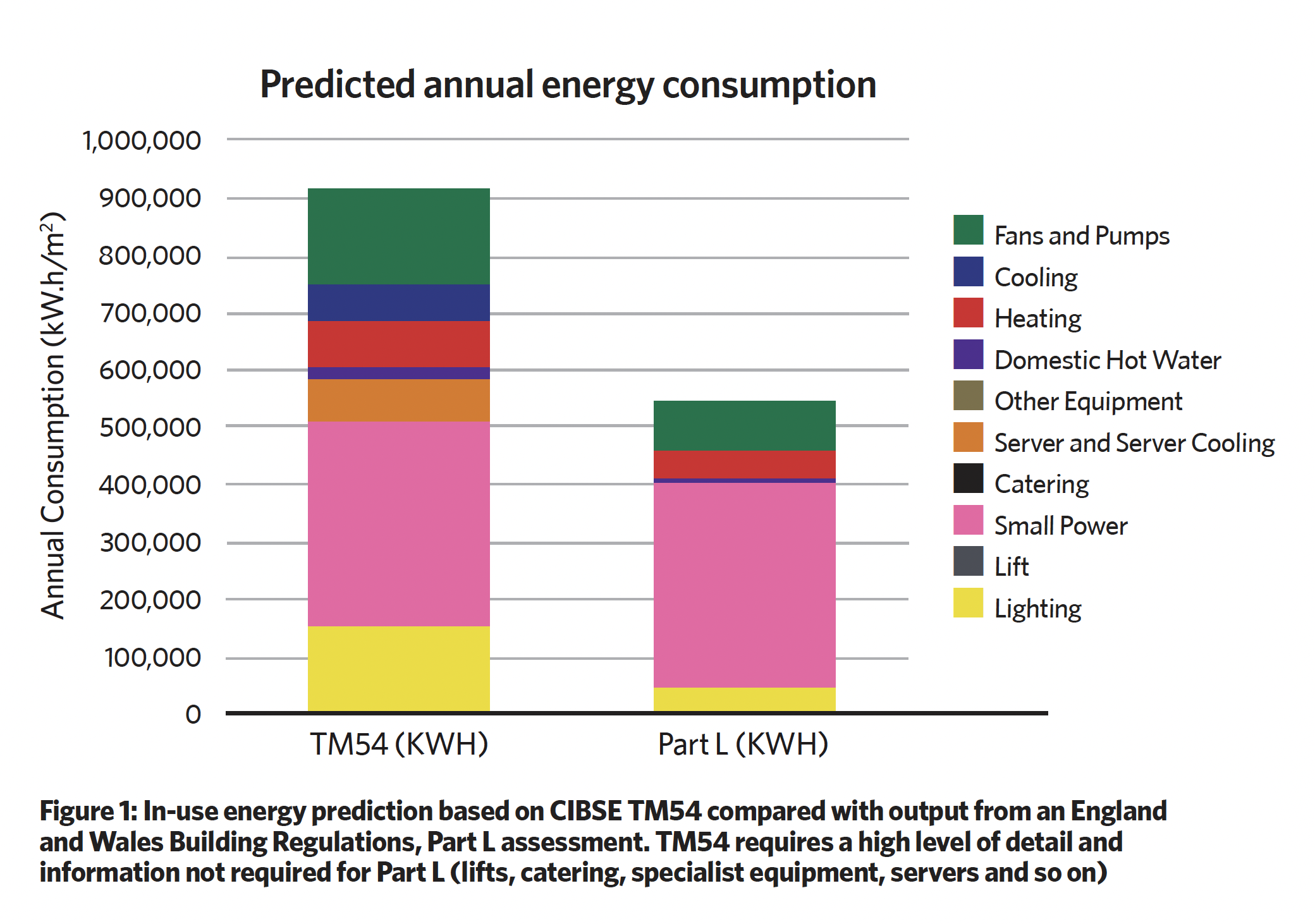

This increasingly accurate assessment of the predicted energy use, informed by CIBSE TM54, requires information relating to the operational phase – such as lift information and catering specialist equipment. This provides a better interpretation of the likely energy consumption and typically gives a higher figure than may have been otherwise expected from the output of compliance checking.

Catchpole gave an example, illustrated in Figure 1, of a predicted energy use informed by CIBSE TM54, compared to Building Regulations Part L.

Depending on the software used for the project, in parallel with the ‘thermal’ model there will probably be an architectural model, a structural model, and one that is employed to develop the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, he explained.

Working within a single common data environment allows integrated cross-discipline analysis, such as clash detection

Working within a single common data environment – where underlying building definitions are common to all models – allows integrated cross-discipline analysis, such as clash detection. Designers, for example, can see if ductwork is cohabiting the same space as the structure and, if necessary, make a swift, pre-construction resolution between the building services and structural engineers.

The CDE-connected models also enable detail-rich information to be readily shared from the model to, for example, user-friendly reader software that allows clients and staff responsible for the eventual building operation to take a look at their prospective buildings with virtual walkthroughs and plantroom visualisations.

Catchpole noted that producing construction operations building information exchange (COBie – a non-proprietary data format) output from the model provides product data information on the physical assets that can be exported to spreadsheets and, ultimately, imported into software (often referred to as BIM models) used for building operation and maintenance.

This product data can be searched to produce plant and equipment schedules, and, in an ideal world, used by contractors to create materials lists and pricing information. The rich data sources also enable and extend the opportunities for modern construction techniques, including prefabrication. Catchpole extolled the advantages of modular construction, noting that ‘high-quality, precision engineering, constructed in a factory, has to be the future’.

Encouragingly, he remarked that, in the UK, there are buildings coming into operation that have been fully designed and built employing a BIM platform and the facilities management teams are starting to see some real operational benefits. This fully integrated approach opens up opportunities to assess whole carbon impacts of design and operation throughout the whole building life, he added.

Catchpole finished his presentation by noting that the industry is not yet in a place where digital tools can be used on every job. Where they can, however – particularly in conjunction with prefabrication and modularisation – it is more likely to produce cost-effective, sustainable built environments.

A platform for building services

In the next presentation, Stuart Cameron, director and MMC lead at the Hive Group, was keen to illustrate how applications of new methods of construction – design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) and modular mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) – were changing the status of MEP. He said modern methods were altering the perception of MEP from simply ‘an installation’ in the programme to one of a prioritised product, and this was improving the quality, speed and sustainability of projects and buildings significantly.

Cameron explained that modules designed for construction within a factory environment remove the uncertainties of the building site; the completed module or sub-assembly is delivered and installed on site to contribute to a completed building.

This can also better enable a circular economy – with closer control of materials and sub-assemblies – reduce waste, and help mitigate the shortage of skilled site workers. Modular buildings maximise resources and promote the reusing and recycling of materials, thereby closing the loop and meeting the requirements of a circular economy.

Cameron illustrated the application of modular construction with examples including an off-grid hotel project in a remote island location just off the Shetland Islands. This was a fully ‘volumetric modular’ construction (large building elements that can be linked together to form complete buildings without the need for an additional superstructure) using cross-laminated timber, with the MEP installed as sub-assembly units.

Fully volumetric modular construction was used on a Shetland hotel project

These assemblies were prefabricated off site, in a factory 650 miles south of the site, in Sheffield, where 95% of the MEP was installed, requiring only final connections on the island, including horizontal and vertical connections.

The method allowed improved accuracy in digital modelling and optimisation, while the quality benefited from being fabricated in a clean, dry, warm environment. When delivered to site as an assembly, the construction becomes more of a product insertion rather than a full, component-based MEP installation.

Cameron reported that the accelerated construction programmes provided swifter returns on investment for developers, and delivered the completed project more quickly to building users.

When applied to housing projects, he considered that up to 90% of construction installation works may be completed within the factory. By referencing a 2019 independent report, Cameron suggested that they require 67% less energy than traditional building techniques, with lifetime energy savings of up to 90%, and up to 60% less waste across all disciplines, including MEP, so delivering reduced carbon footprint.

A recording of the complete seminar, including all five speakers, is available to watch (for a registration fee) in the virtual ASHRAE 2023 Winter Conference at bit.ly/CJMar23TD