Haringey was the first council in London to provide Modulhaus homes

The CIBSE Building Performance Awards judges described Volumetric’s Modulhaus as a ‘stand out’ winner of the 2023 Wellbeing award. They said the company’s stackable, modular homes, designed for rehousing rough sleepers, made a significant contribution to the wellbeing element of building performance, describing it as ‘a sustainable solution for temporary accommodation that is an attractive mix of innovation and societal good’.

Volumetric Modular is a specialist manufacturer of modular accommodation. It was given the brief to develop the accommodation module by Foundation200, a charity set up by Andy Hill, chief executive of housebuilder Hill Group (and a director of Volumetric), with a pledge of £15m to build and gift 200 homes for the homeless.

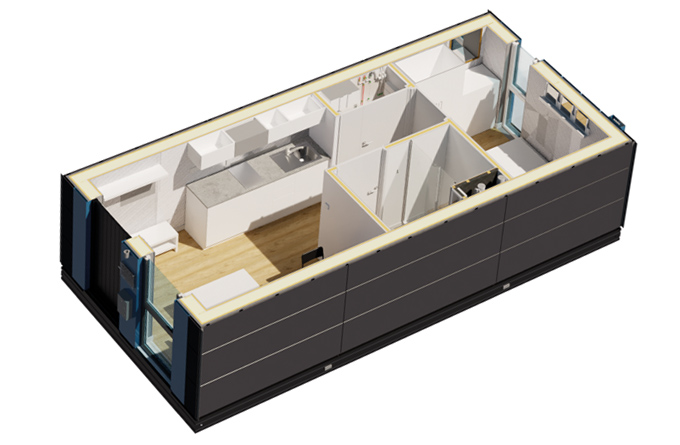

Modules arrive on site fully fitted and furnished

Foundation 200 had already spent time talking to charities to help it understand what was needed when devising an interim housing solution for the homeless. ‘The brief for a single-person home that was put together by the Hill Foundation200 team for Volumetric outlined its ambition to create a home that would give someone pride in the place they are living in,’ says Trevor Richards, operations director at Volumetric.

… a sustainable solution for temporary accommodation that is an attractive mix of innovation and societal good

Volumetric was given a target cost per module, but Richards says the manufacturer was not held rigidly to this figure ‘because we were building something new compared to what is currently on the market and aiming to future-proof the design ahead of the 2025 Future Homes Standard’.

The adoption of a modular approach to the provision of accommodation for the homeless helped the proposal address several specific issues, including overcoming the challenge of building on confined sites and enabling the homes to be relocated, should circumstances change.

‘Some of the first locations were for garage infill sites, which are small plots that are difficult places on which to build,’ Richards explains. ‘While the development will provide permanent, Building Regulations-compliant homes with a postal address, there may come a time when they will need to be relocated and, being modular, they can easily be picked up and moved elsewhere.’

Volumetric modules installed in Cambridge

Each module is built around a robust steel frame infilled with profiled steel panels, which is strong enough to enable the 11-tonne modules to be moved and to be double-stacked. The profiled steel panels have a two-hour fire rating, both inside-to-out and outside-to-in, which provides complete flexibility in module location by enabling them to be positioned close to an adjacent property. ‘We’re not building a house for a specific plot; our difficulty is that we do not always know where a unit is going to be located so that means we have to work to the worst-case scenario,’ Richards explains.

As with most volumetric construction methods, the module’s dimensions are driven by road transportation restrictions. Richards says: ‘A Solohaus module’s footprint at 3.86m wide, 7.93m long and 3.14m high, is based on what is transportable without the need for a police escort.’

We spent quite a lot of money ensuring the modules looked good externally by trying to soften the look and make occupants proud…

Modules arrive on site fully fitted and furnished and containing an occupier ‘welcome pack’. The Solohaus module incorporates a bedroom, sized to allow just enough space for a single bed to stop others moving in and taking advantage of a vulnerable person, a separate bathroom and kitchen/sitting area. ‘Clever design makes the space feel bigger than it actually is,’ says Richards.

At the time the concept was being developed, Richards says the consultation on the 2021 interim update to Part L was under way. The update was introduced by the government as a first step towards the 2025 Future Homes Standard, which is for a 75% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions compared with one built to 2021 standards.

The interim consultation proposed two CO2 reduction options: a 20% reduction compared with current standards and a 31% reduction. ‘We did not know which option would be adopted, so we had to design for the worst-case scenario,’ he says. As it turned out, the 31% reduction was adopted so this proved to be a wise decision.’

To minimise energy consumption to meet the required CO2 reduction, Volumetric adopted a fabric-first approach. Again, because the modules are standardised and designed to be interchangeable regardless of orientation and whether they form the top or bottom storey of an installation, the wall, ceiling and floor construction is identical on all modules within the range.

The bedroom for the two-person module

Richards says commercially he ‘doesn’t want to give too much away’ about the make-up of the envelope, but he does say that this approach did result in ‘relatively thick walls’. These incorporate 150mm of insulation, while the floor and ceilings are thicker still, with 220mm of insulation. ‘We’ve got significant amounts of thermal insulation and we’ve minimised thermal bridging as far as possible.’

Compliance with Part L was helped by the module’s target air leakage rate of m3·h-1·m-2 at 50Pa. ‘We’re working in a factory environment so our ability to control quality and maintain a more consistently airtight product is much easier,’ Richards explains. ‘Under our LABC accreditation, we test one in 10 modules to ensure we were getting less than the three air changes per hour target.’

The module’s relatively airtight envelope means that fresh air is provided by an MVHR.

A render of the Familyhaus+ module

The MVHR also helps keep the module comfortable in summer, without the windows being open. ‘Because this is a self-contained unit with a bedroom, it means that when the module is located on the ground floor the occupant cannot rely upon opening the window to provide ventilation because of potential concerns over security and we didn’t want to add mesh to the windows because we felt that would create the wrong image,’ says Richards.

In addition, to help minimise peak summer internal temperatures, the modules feature high-density layers of lining boards to add thermal mass. Blackout blinds are also fitted to the windows.

A bunk bed in the family module

‘As part of our preparations for the introduction of Part O of the Building Regulations, we modelled the accommodation module in various orientations and at various locations around the country,’ said Richards.

Modelling showed that in London and in some areas of the Thames Valley, the addition of brise soleil or some other form of solar shading would possibly be needed to limit solar gain. ‘If you try to create different modules for different locations you start to lose the benefits of standardisation and efficiencies in the manufacturing process.’

The modules feature an air source heat pump and are designed to take a ‘photovoltaic roof rack’ allowing PVs and batteries to be added at a later date.

Servicing the modules

When the concept was first developed, it featured a shared mini-plantroom module, with a footprint of 1.5m x 1.8m and clad the same as the modules. The plantroom incorporates an air source heat pump (ASHP). This provides heat to a pumped LPHW circuit and a pumped domestic hot water circuit serving six modules. Using lower temperatures for hot-water and with automatic Legionella cycles as standard, the plantrooms are relatively simple to run once installed, says Richards. ‘For larger schemes you just increase the number of energy centre modules,’ he explains.

Early versions of the modules were heated using radiators. However, in later modules these have been replaced by a wet underfloor heating system. Each module has its own thermostat and timer.

The units are available with what Richards describes as a PV ‘roof rack’, which can be added to a module along with a battery to store energy generated. ‘The base model unit, without the battery and PVs has an EPC C rating, but when you add the battery and PVs it becomes an A.’

More recently, following the changes to the SAP methodology to reflect the decarbonisation of the electrical grid, Richards says Volumetric has developed a standalone all-electric module.

Richards says the biggest challenge in rolling out the concept is not servicing the modules but in gaining planning permission for a development. ‘Because these are permanent homes, designed with a lifespan of 60 years and certified under the Build Offsite Property Assurance Scheme (BOPAS), they need planning permission, which is the hardest part of a deployment.’

Volumetric builds and fi ts the modules offsite

He says that Volumetric can change the modules’ appearance for planning. ‘We know it is now standardised technology, and that because it is modular it has a particular look to it, so we spent quite a lot of money ensuring the modules looked good externally by trying to soften the look and make occupants proud of their homes,’ he says. ‘But being a manufacturer we like consistency, but on a number of schemes we have changed the colour schemes and are looking at a brick slip option.’

The scheme that won the Wellbeing category of the CIBSE Building Performance Awards was the Solohaus home designed specifically for one person. Following its success, Volumetric has now increased its range of modular accommodation to include the Duohaus for two people and the Familyhaus. All the modules are interoperable and can be configured to create mixed-use and mixed tenure schemes and on-site accommodation for key workers.

The kitchen in the family house