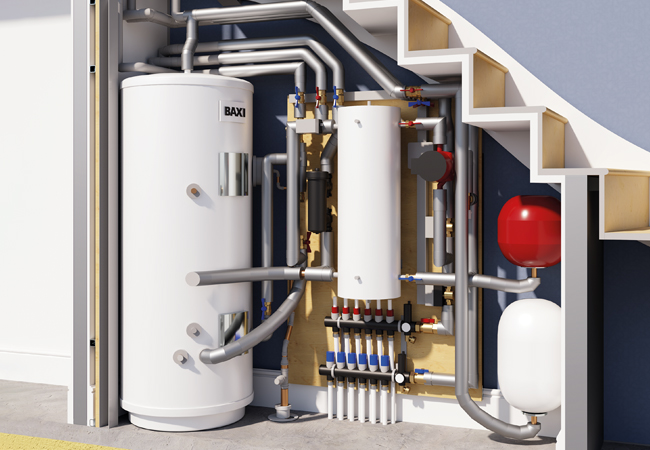

A cutaway view of a WholeHouse design

To meet the UK’s carbon-reduction targets, the Prime Minister’s Ten-Point Plan established an ambition to grow the heat pump market to 600,000 installations per year by 2028.

The current reality is that a paltry 60,000 were installed in the UK last year – which, at two heat pumps per household, put the country at the bottom of the European heat pump league.

To increase the number of installations in new homes, the government is taking a ‘big stick’ approach and proposing to ban gas and oil boilers in new homes from 2026.

It’s a huge challenge, especially for small to medium-sized housebuilders that are familiar with gas boilers, and may not have the resources to design and develop homes based on alternative heating systems.

Building merchant Travis Perkins has recognised this predicament and launched a digital platform called WholeHouse, aimed at streamlining the design and delivery of low carbon homes.

Lee Jackson, WholeHouse director at Travis Perkins, says the industry lacks the skilled workers required to meet government heat pump targets, and a new digital approach is required that simplifies design and installation, and encourages the prefabrication of building systems.

‘I’ve opened too many airing cupboards where I’ve been met by a wall of pipework that’s 15 layers deep,’ says Jackson. ‘The average plumber has spent years installing combi boilers, and now they are expected to put back in a cylinder and install an air source heat pump [ASHP].’

Without help, Jackson believes plumbers will have to learn from job to job, and will deliver inefficient heat pump systems until they have gained experience.

Baxi’s is the only appropriate heating system featured in the software at the moment

WholeHouse is a 3D online design tool that allows the housebuilder to design any size home using a variety of materials and systems, including heat pumps. The software has strict parameters to ensure whatever is selected leads to the most energy efficient and cost-effective design possible. Once a design is settled on by the user, the program produces a set of drawings and the bill of materials in just 45 minutes.

In developing the software, Travis Perkins assembled a team of 20 suppliers and consultants to come up with design parameters that guarantee the software’s outputs are optimised for cost and energy efficiency.

‘Upfront design is undervalued in housebuilding,’ says Jackson, who is a trained architect. ‘It’s critical, with new technologies, to make sure the design is correct – then we have a fighting chance of delivering what we intend to.’

It’s critical to make sure the design is correct – then we have a fighting chance of delivering what we intended to do

Some designs, such as the heating system, can be prefabricated off site, which cuts down on waste and reduces the need for people on site. Jackson calls this process ‘the industrialisation of design’.

The designs are incorporated in the software, alongside the latest housing standards and calculation methods, including SAP 10 and the CIBSE TM59 Overheating risk calculation, which is included in the latest Part L of the Building Regulations. This means that if users change window sizes, for instance, the software will automatically adjust other elements – such as insulation – to ensure compliance with Building Regulations.

Radiator sizes will be adjusted according to whether a boiler or heat pump is used as the heat source, and the system automatically inserts the most efficient pipework runs for plumbing, and ductwork for ventilation, positioning the necessary voids and holes in the floors and joists. It can include photovoltaics and decentralised mechanical extract fans, while more sophisticated mechanical ventilation with heat recovery units are also included.

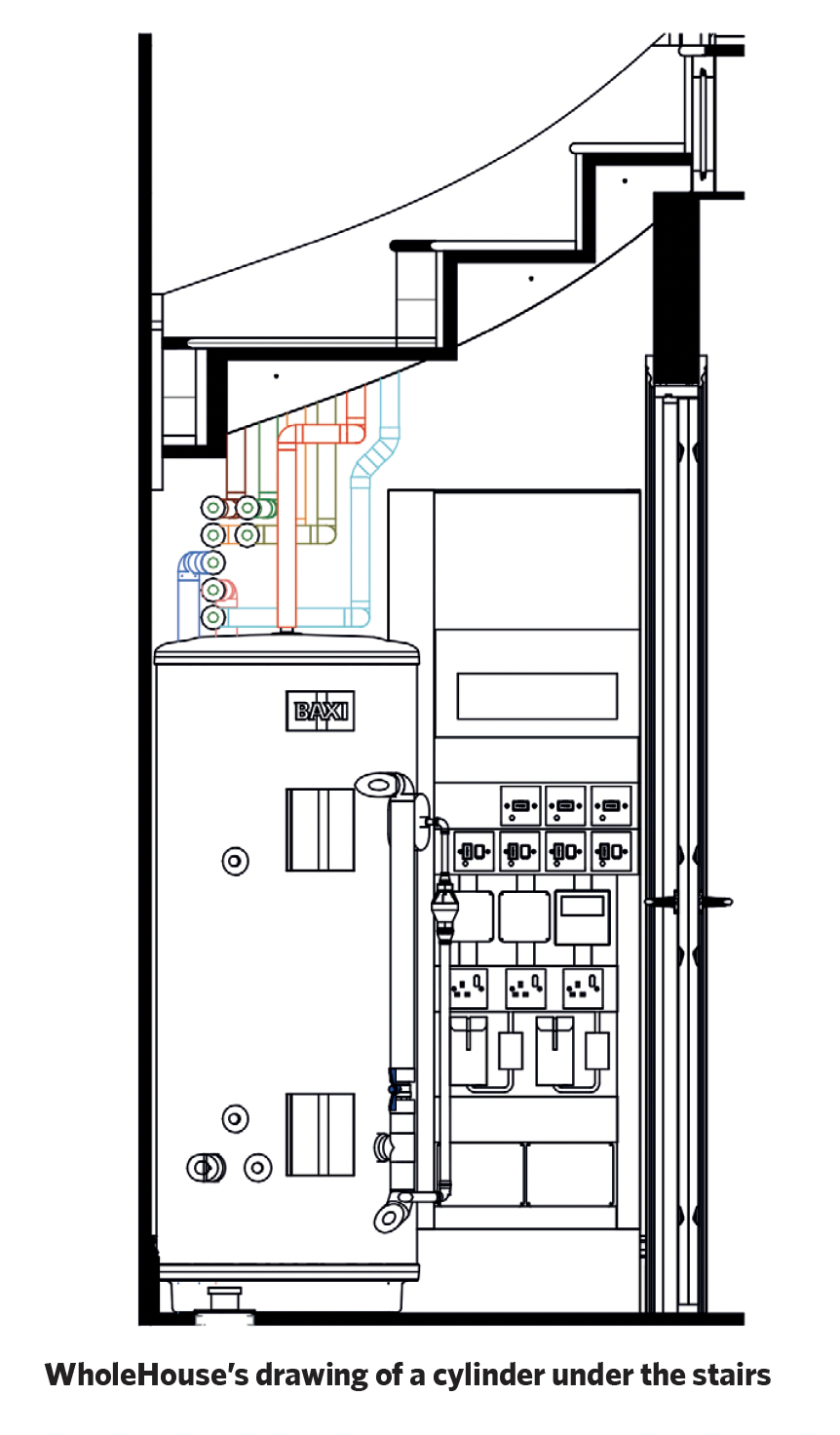

One of the design partners is Baxi Heating, which supplied details of 160 understairs configurations featuring its range of ASHPs, water cylinders and pumps. (Gas boilers are also included.)

Andrew Miele, senior application engineer, offsite, at Baxi, was responsible for ensuring the design outputs did not feature a tangle of pipes in the understairs cupboard. By working with other partners on the design, he was able to ensure the plantroom was as streamlined as possible and could be prefabricated in the Baxi factory.

A prototype helped Baxi position its heating system under the staircase

It was decided by WholeHouse team to locate the cylinder under the stairs with the rest of the heating system, because it only took up 0.9m2 of floor space compared with 1.5m2 of floor space if it was in an upstairs utility cupboard.

Baxi worked closely with staircase manufacturer Staircraft to devise an efficient heating design that worked in the spaces created by the risers and treads. Staircraft provided Baxi with a staircase to create a prototype that validated software designs and calculations. The mock-up will soon be installed at a Baxi training facility.

To improve the efficiency of the design, Baxi also requested that a wall be moved 100mm, something that would have been impossible in a regular build, where Baxi would have come onto the project at a much later design stage.

Miele says he was given much more time to optimise the design: ‘In other projects, I will try to feed in design suggestions, but you can only make limited changes. Whereas here, everything’s up for discussion.

‘Going into this amount of design detail was of great benefit to us, because we can then repeat the design in the factory.’

Baxi used its experience with prefabricated utility cupboards and commercial heating and cooling systems to feed into the design discussions.

With more standardisation of design and repetition, offsite manufacturers will be able to achieve better economies of scale, says Jackson. They will also be able to plan for production because WholeHouse knows when working designs have been downloaded and when materials and systems need to be manufactured. ‘The visibility means that Baxi can make sure its supply chain is always sized to suit the demand coming through,’ says Jackson.

Accounting for embodied energy

WholeHouse is looking to include embodied energy figures in the software to allow whole carbon calculations to be made. If a manufacturer has an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD), this will be plugged into the software and replace generic figures in the calculations, to give better overall results for carbon. Recognising the low embodied energy of their products will be a ‘commercial benefit for manufacturers to use EPDs’, says Jackson, who adds that the accurate designs and prefabrication will help minimise the number of components required and the amount of overall waste.

Any manufacturer can potentially have its products featured in WholeHouse – there are a number of suppliers’ door kits featured, for instance – but Jackson says Baxi’s is the only appropriate heating system featured at the moment.

A digital twin of the house is created, which can be used in the future if, for example, the occupier wants to add an extension (the project teams purposely created designs that could be extended in the most efficient and economical way possible).

It has not yet been decided who takes ownership of the digital twin – it could be WholeHouse or it could be the regional housebuilder. ‘It will be whoever adds the most value,’ says Jackson.

The first two houses designed using the system are nearing completion and Jackson has ambitious plans for the system. As well as targeting the SME housebuilder market of up to 2,000 companies, he thinks it could also be used by selfbuilders and major housebuilders, with whom he is already in discussion about using elements of WholeHouse.

Jackson has also had talks with the Health and Safety Executive about incorporating manuals into the software and highlighting known safety issues. ‘We can bring more people to WholeHouse to refine the software further and iron out other issues,’ he says.

While Travis Perkins is advocating a standardised approach, it doesn’t mean that homes will look the same everywhere. This is part of the appeal to regional housebuilders, as they can reference the local vernacular with their choice of materials, says Jackson.

There is ‘beauty in standardisation’, he adds, with some of Britain’s best, most historical housing being based on only two or three house types, such as the Royal Crescent in Bath and Islington’s Georgian townhouses.

‘Pattern books are a fundamental part of our history of architecture and the landscape of towns and villages,’ says Jackson, who is talking to The Prince’s Foundation about using WholeHouse in heritage developments.

‘We tend to associate the term “house types” with some of the homes that major housebuilders churn out, but we shouldn’t think of standardisation in that way,’

says Jackson.