The Tropical Fruit Warehouse

As buildings are required to become more operationally efficient and produce less carbon, embodied carbon is accounting for a greater share of their life-cycle carbon production.

The retention and reuse of a building can limit additional carbon production and policy makers across the UK and Europe are increasingly requiring developers to justify their decision to demolish existing buildings.

Dublin City Council’s 2022-2028 development plan, for example, requires ‘robust justification’ for demolition and reconstruction works and that re-use should always be considered as a first option.

The policy appears to be having an impact, with property agent Savills saying that ‘emerging evidence points to [the retention and reuse of buildings] as best practice,’ for many developments in its 2023 review of the Dublin office market.

The following contrasting schemes show how consultant engineers in Ireland are helping to trailblaze the reuse of two very different types of office building.

Tropical Fruit Warehouse

A warehouse building, formerly used for tropical fruit imports (and more recently as a studio by U2), on the quays of the River Liffey in Dublin, has been redeveloped as an office building.

Owned and developed by IPUT Real Estate, designed by architect Henry J Lyons, built by Dutch design and build contractor Octatube, with a façade designed by Arup and building services by O’Connor Sutton Cronin, the scheme comprises three interconnecting elements: a restored 1890s warehouse with a new lightweight cantilevered glass box extension above and a new seven-storey office building behind.

Reuse of the fabric of the double-bay existing warehouse reduced the carbon embodied in the project. A two-storey glass-box extension appearing to float above these is the most eye-catching part of the project.

The early involvement of Arup’s façades team ensured that the lightweight, transparent box could be delivered in keeping with the architectural aspirations.

The double-skinned façade features an outer skin of 8.5m high, 2.5m wide giant laminated glass panes, that reach full height of the two-storey box. The inner double-glazed skin, forming the building’s thermal envelope, is a bespoke steel and glass module. It is recessed top and bottom to give it the appearance of being frameless; all the occupants see is a thin black silicone 24mm-wide vertical joint between units. The double-skin façade has a U-value of 1.1 W·m-2·K-1.

The location of the glass box above the existing warehouses meant that when it came to constructing it, sequencing was key

A series of glass fins, positioned in line with the joints on the outer leaf, separate the outer leaf from the inner unit. The fins are hung from the building’s roof. The weight of the outer glazed skin is supported on a bespoke stainless steel frame fixed back to the bottom floor slab.

‘We worked diligently with the contractor to develop bespoke toggled connections that allowed accommodation of the differential vertical movements with the fins providing horizontal restraint to both skins,’ explains Lee Corcoran, senior façade engineer at Arup.

An additional movement challenge was that the cantilevered structure onto which the façade was attached was predicted to deflect under imposed loads.

Corcoran says: ‘We worked closely with Octatube and structural engineers Torque Consulting Engineers to fully understand the movements associated with the structure at façade connection points so that we could design the system to accommodate the anticipated racking movements and minimise the joint sizes with minimal visual impact.’

The glazed corners of the outer skin were carefully considered through extensive structural calculations and detailing. The final solution to ‘lock’ the corner units incorporates a closed loop structural solution; the large glass panels transfer the lateral load into bespoke stainless steel connections and concealed stainless steel tension rods hidden within the silicone joints at the head and base of the units.

‘It is a fantastic, discrete solution that no-one will ever see, which is aligned with the essence of the project,’ says Corcoran.

Arup used a low-iron glass for enhanced clarity in both the inner and outer units.

In the drive to maintain transparency, the architect was keen that the office floors were kept free of window blinds and that the double-skinned façade remained uncluttered by interstitial maintenance walkways.

A high-performance solar control coating on the outer skin of the double-glazed unit combined with a solar control PVB interlayer on the laminated single-layer outer skin and ventilation to the interstitial cavity removes excess heat.

The biggest modification by far is the introduction of a new atrium punched through the centre of the building, to allow daylight to enter

To finalise the glazing and PVB selection, Octatube built a series of small-scale mock-ups at its Delft HQ. Once the selection was confirmed, a full-scale mock-up was built and subjected to the CWCT sequence B weather performance test.

Access for cleaning within the cavity is provided by a single walkway concealed at the base of the façade. To enable personnel to move between the two skins, Arup worked with Octatube to shorten the glazed fins so that they stop 1.6m above this walkway. A bespoke abseiling solution was developed to allow for cleaning of individual bays in between the glass fins.

The location of the glass box above the existing warehouses meant that when it came to constructing it, sequencing was key. As part of the restoration of the warehouses, all of their roof trusses were removed and taken off-site for restoration. This allowed construction of the core and structure to support the glazed box. The box was pre-assembled as far as possible to minimise work at height, ensure build quality and to complete the installation before the warehouse roof trusses were reinstalled.

‘What made the project so successful was our involvement at such an early stage, which meant the design was well considered quite early in the process and that allowed us to engage with a specialist contractor very quickly,’ Corcoran says.

The 85,000ft2 office is now entirely leased to TikTok.

Tom Johnson House

Tom Johnson House is a five-storey 1970s office that will become home to Ireland’s Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications

The retrofit of Tom Johnson House, Dublin, is set to turn a five-storey over-basement, 1970s office building into one of the most sustainable buildings in Ireland, ready to become the new headquarters for the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications (DECC).

The Irish Government has made it a top priority to decarbonise public sector projects and drive the green transition to help mitigate climate change. This project, funded by the EU under Ireland’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021 as part of the European Union’s response to the global pandemic, is intended to be an exemplar.

It will demonstrate that the project’s client, the Office of Public Works (OPW), is helping lead that transition. As such, Tom Johnson House has been designated a Public Sector Retrofit Pathfinder Project by the OPW.

Designed in-house by the commissioners of public works in Ireland and engineered by Lawler Consulting, the refurbishment is designed to take the building from a C3 Building Energy Rating to an A2, which the OPW predicts will reduce primary energy use by 75%, greatly extending the building’s useful life. ‘The OPW brief was for the building to be A2 energy rated; that set strict criteria for what we had to achieve in terms of both fabric and MEP systems’ energy performance,’ says James Long, associate director at Lawler Consulting.

Application of the OPW’s Green Procurement Policy will further mitigate the project’s carbon impact as will the requirement for compliance with EU rules for material input and waste management, re-use and recycling.

The retrofit retains the existing 1970s concrete structure and external brick façade to minimise the carbon embodied in the refurbishment. ‘We’ve reused the existing window openings and fitted new glazing to enable the office to be naturally ventilated,’ explains Long.

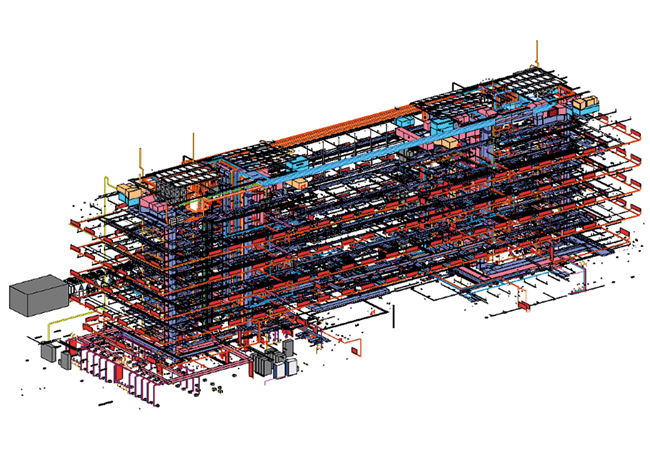

A BIM model of Tom Johnson House

Internally, the existing cellular office layout has gone, to be replaced by a predominantly open plan office arrangement.

The biggest modification by far, however, is the introduction of a new atrium punched through the centre of the building, from roof to ground floor, to allow daylight to enter deep into the building’s core and to further facilitate natural ventilation.

The new atrium divided the existing rooftop plantroom into two halves. As a result, Lawler Consulting’s scheme now serves each half of the building from its own dedicated rooftop plant. ‘We’ve lost a third of the plant space and yet we’re going to deliver enhanced levels of comfort,’ says Long.

Lawler Consulting’s all-electric design includes removal of the existing boilers. These are being replaced by two, 600kW multifunction chiller heat pumps to provide both heating and cooling to the offices.

A smaller high-temperature heat pump boosts the heating water temperature to heat the domestic hot water. There is no fossil fuel on site.

Office floors are heated by radiators on a low-temperature hot-water system. High occupancy areas, such as meeting rooms, all incorporate active cooling, primarily provided by fan coil units.

Additional carbon reductions are provided by a 50kW roof-mounted solar PV array.

The scheme also incorporates a large number of EV charging stations. These are controlled to ensure the building’s electrical demand remains within the capacity of the site’s existing 600kVA transformer.