Our health and wellbeing are impacted by the presence of airborne pollutants. In response to our growing awareness of this, indoor air pollutant monitoring is becoming more commonplace. However, air quality is not always regulated inside buildings, so how do owners and occupiers know if their building’s air quality is good, bad or even illegal?

Secondary legislation regulations and guidelines are being used as the working values against which indoor air quality (IAQ) can be assessed.

It can be regulated via health and safety regulations, such as the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) Regulations (2002), to which all places of work have to adhere. Regulation 6(1) of COSHH states that an employer ‘should carry out a suitable and sufficient assessment of the risks to the health of your employees and any other person who may be affected by your work, if they are exposed to substances hazardous to health’. Regulation 10 of COSHH specifies that monitoring is required ‘when measurement is needed to ensure a workplace exposure limit (WEL) or any self-imposed working standard is not exceeded’.

There are legally binding WEL for around 500 substances, listed in HSE EH40/2005. However, WEL only relate to personal (exposure) monitoring of people at work, are calibrated for a healthy working-age adult, and can’t be readily adapted to evaluate or control prolonged, continuous or non-occupational exposure. So, for most office and education settings – and all public and residential buildings – WEL cannot be used to assess building occupant exposure to IAQ.

New buildings, however, are covered by the recently updated Statutory Instrument Building Regulations (2010). Now included in Approved Document F1 is ‘Means of Ventilation’, providing statutory guidance on ventilation requirements to maintain IAQ.

Within Approved Document F1, Appendix B: Performance-based ventilation, average indoor air pollutant guideline values are set for carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), formaldehyde, total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) and ozone (O3), largely based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. However, as the document relates to building performance guidance, these values are performance criteria of the assessment of ventilation, not occupant exposure assessment criteria.

For several years, regulations, standards and guidance on IAQ for school buildings have been set out in the UK government’s Education and Skills Funding Agency Building Bulletin BB101. This includes guidelines on ventilation, such as setting a maximum CO2 in teaching spaces, and specific guidelines on IAQ, mainly based on WHO guidelines that ‘should be used for schools’.

The WHO first published air quality guidelines in 1987, which have been updated since. They ‘serve as a global target for national, regional and city governments to work towards improving their citizens’ health by reducing air pollution’.

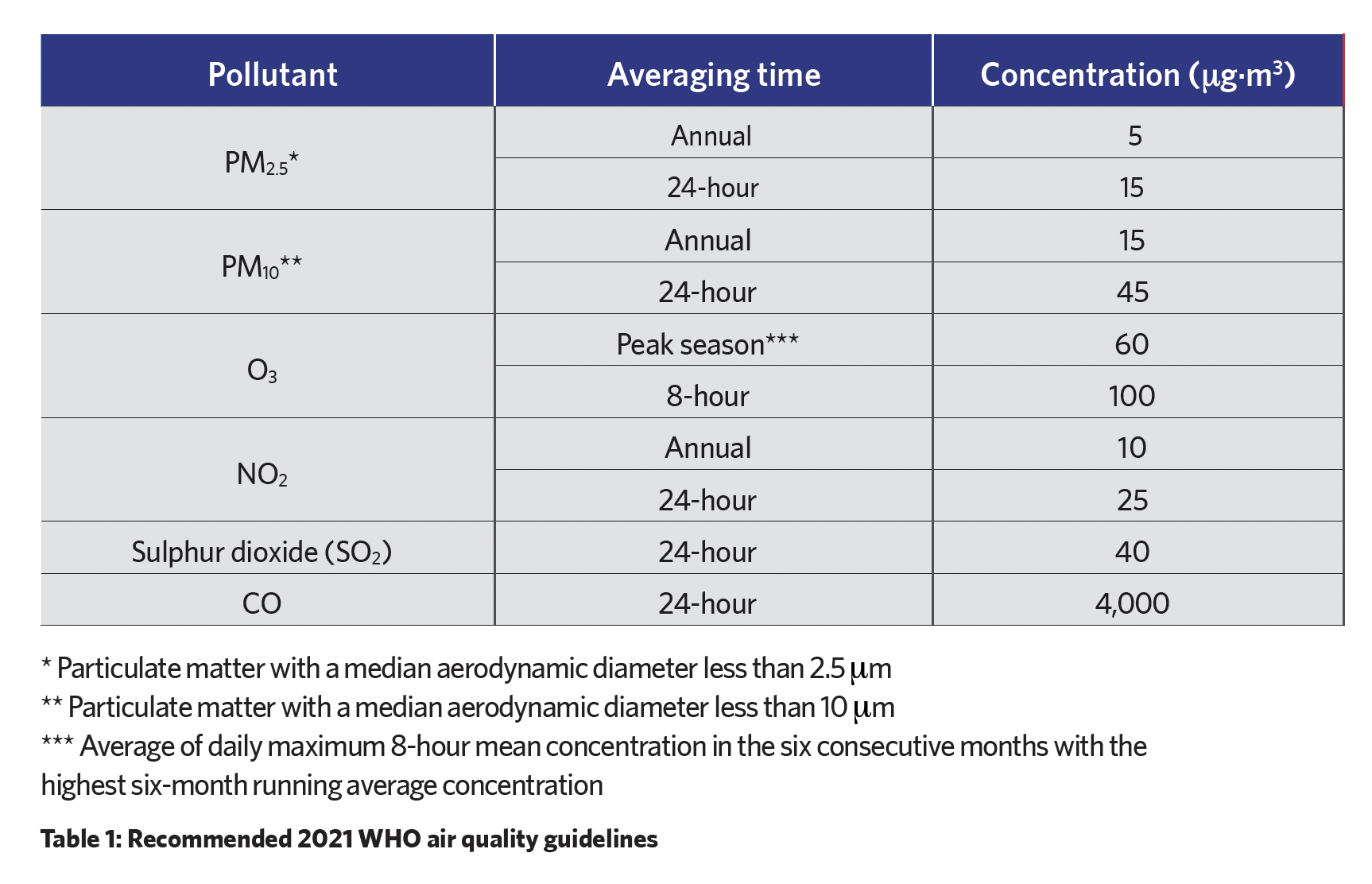

In 2010, the WHO published guidance on risks associated with pollutants commonly found in indoor air (benzene, CO, formaldehyde, naphthalene, NO2, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, radon, trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethylene), and updated their (general) air quality guidelines in 2021 (see Table 1).

It should be noted that WHO general air quality guideline values ‘do not differentiate between indoor and outdoor exposure’, so they are applicable indoors. Some of the latest 2021 guidelines supersede its specific 2010 IAQ guidelines (eg, for CO and NO2).

They are relevant in all countries and in all exposure settings where COSHH WEL are not appropriate. Organisations, including CIBSE, point to these guidelines for IAQ monitoring. In recent years, other organisations have published IAQ guidance.

Recent guidance

UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology: POSTbrief 54 IAQ (2023) bit.ly/CJIAQPost54

CIBSE TM40 Health and wellbeing in building services (2020) bit.ly/CJTM40

CIBSE TM68 Monitoring indoor environmental quality (2022) bit.ly/CJTM68

CIBSE TM64 Operational performance: Indoor air quality (2020) bit.ly/CJTM64

Defra Air Quality Expert Group: Indoor air quality (2022) bit.ly/3QY72FW

Institute of Air Quality Management Indoor air quality guidance: Assessment, monitoring, modelling and mitigation (2021) bit.ly/CJIAQAMMM

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Indoor air quality at home (2020) bit.ly/CJNICEIAQ

Public Health England (now the UK Health Security Agency) Indoor air quality guidelines for selected volatile organic compounds in the UK (2019) bit.ly/CJPHEVOC

About the author

Oliver Puddle is technical director at DustScanAQ