Paris 2024 is being hailed as the greenest Olympic Games in history. The organisers are aiming to halve the event’s carbon footprint, to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2, compared with previous games in London (2012) and Rio (2016), which emitted 3.4 and 3.6 million tonnes of CO2 respectively. The target is even lower than the 1.9 million tonnes of CO2 emitted at Tokyo’s Covid-19 Olympics, which had no spectators.

To meet this ambitious target, the plan is to do away with diesel generators and to connect all the Paris Olympic sites to the electric grid (London 2012 reportedly burned four million litres of diesel to power its venues).

Of the two million pieces of sporting equipment that will be used, three-quarters will be rented or provided by sports federations. More than 75% of the electronic equipment, such as computer screens, will also be rented, as will many of the venue tents. In addition, 25% of the ingredients for the meals served to spectators and athletes will be sourced locally.

Project team

Client: Métropole du Grand Paris

Main contractor: Bouygues Bâtiment Ile-de-France

Operator: Récréa

Maintenance: Dalkia

Architects: VenhoevenCS and Ateliers 2/3/4/

Structural engineer: Schlaich Bergermann Partner

MEP: INEX

Water treatment: Katene

Acoustic consultant: Peutz

Sustainability consultant: Indiggo

The most sustainable element of the Games, however, is what the organisers are not doing: building new venues. Instead, many of the city’s existing venues are being repurposed, including the Stade de France – built for the 1998 Football World Cup – which is being transformed into the main arena.

The one major exception to this reuse edict is the new, purpose-built Aquatics Centre – but even this incorporates a timber structure and uses recycled materials in its fit-out. Most importantly, after hosting the Olympics, the centre will be transformed into a multi-sports facility for the local Seine-Saint-Denis community for the next 50 years.

The Aquatics Centre has been constructed under a design, build, finance, maintain and operate contract by Bouygues Bâtiment Ile de France consortium, working with architects VenhoevenCS and Ateliers 2/3/4, along with MEP engineers INEX. The building’s form has been kept deliberately compact to minimise construction costs, the quantity of materials needed and the energy required for the legacy phase of its operation.

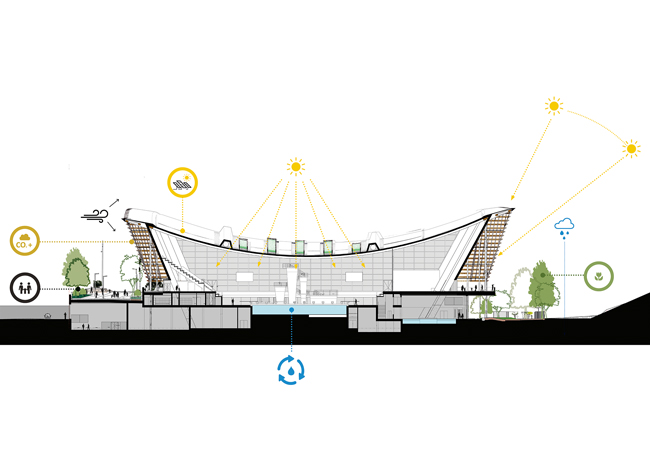

A section view of the Aquatic Centre’s sustainability features

Its thin, curved roof is the venue’s most distinctive feature. This is highest above the diving tower and the raked spectator stands that flank the pool north and south. From here it swoops down towards the swimming pool and the lower, less-imposing community-facing west façade.

According to Cécilia Gross, partner-director at Dutch architect VenhoevenCS, the roof’s hollowed out, concave shape reduces the volume of the hall compared with designing a box. ‘We are not talking a little reduction – we are talking about halving the volume and thus helping minimise the energy required to condition the air filling the arena,’ she says.

One 71m-long pool incorporates two movable walls to allow it to be configured into a 50m swimming and 20m diving pool

The roof is supported on a lean catenary structure of 91, individually curved, timber glulam beams, which are just 500mm deep and 200mm wide, and span the 89m width of the building. The beam’s slender profile helps minimise the void between beams, which co-architect Laure Mériaud, a partner at Paris-based Ateliers 2/3/4, describes as ‘wasted space that would require energy to heat’.

Lateral stability of the timber structure is provided by a timber deck. There is no ceiling, so the timber beams and deck are visible from the pool hall, as is the cabling, lighting and small air conditioning ducts. The larger, main distribution ductwork is located on top of the roof, so as not to detract from the structural form.

Timber louvres provide solar shading for glass elevations

The roof incorporates 5,000m2 of photovoltaic panels. These provide up to 20% of the centre’s electrical demand. Rainwater is also harvested by the roof and stored in a subterranean tank for use in irrigating the surrounding planting.

Timber louvres form a slatted enclosure surrounding the building, which offers solar shading for the centre’s fully glazed east and west elevations, and creates a sheltered colonnade for pedestrians. Gross says daylight from these glazed elevations brings ‘magic’ to the building, although the glass will be covered for the Olympics, to give the TV crews complete control of the lighting.

The reinforced, low carbon concrete pool is also designed to minimise the volume of water required. Rather than construct multiple pools for the diving, swimming, water polo and artistic swimming competitions, there is just one, 71m-long pool. This incorporates two movable walls to allow it to be configured into a 50m swimming and 20m diving pool, or a 33m pool to host water polo or artistic swimming and a diving pool.

The depth of the pool varies, too; it is at its deepest for the diving, but slopes up towards the west, where the swimming and other events will take place. Sculpting the floor means it contains 25% less water, which does not need to be kept warm or treated over the lifetime of the building. In addition to movable walls, the pool has a movable floor to further increase its versatility when operating in legacy mode.

The Paris 2024 Aquatics Centre is a fitting showcase for one of the Games’ premier events. Ultimately, however, it is the people of Saint-Denis and other neighbourhoods who will benefit from its transformation after the Games into a multifunction sports facility. The huge bank of 2,500 temporary seats (made from recycled bottle caps) on the north side of the building will disappear, to be replaced by padel tennis courts and pitches for team sports, along with a fitness and bouldering area.