One of the star attractions at the 2016 Ecobuild conference was, literally, out of this world. Foster + Partners showed how lunar modules could be built on the moon using robots parachuted onto the surface.

Partner Xavier De Kestelier said 3D structures could be constructed on the moon and Mars using loose rocks and soil. He told the audience that Foster + Partners envision a 93m2 martian base constructed, layer by layer, from regolith – the mix of soil and loose rock found on the surface of the Red Planet.

The fused regolith creates a permanent shield, with a bird-bone-like structure, protecting the settlement from excessive radiation and extreme outside temperatures, that fall to -125°C.

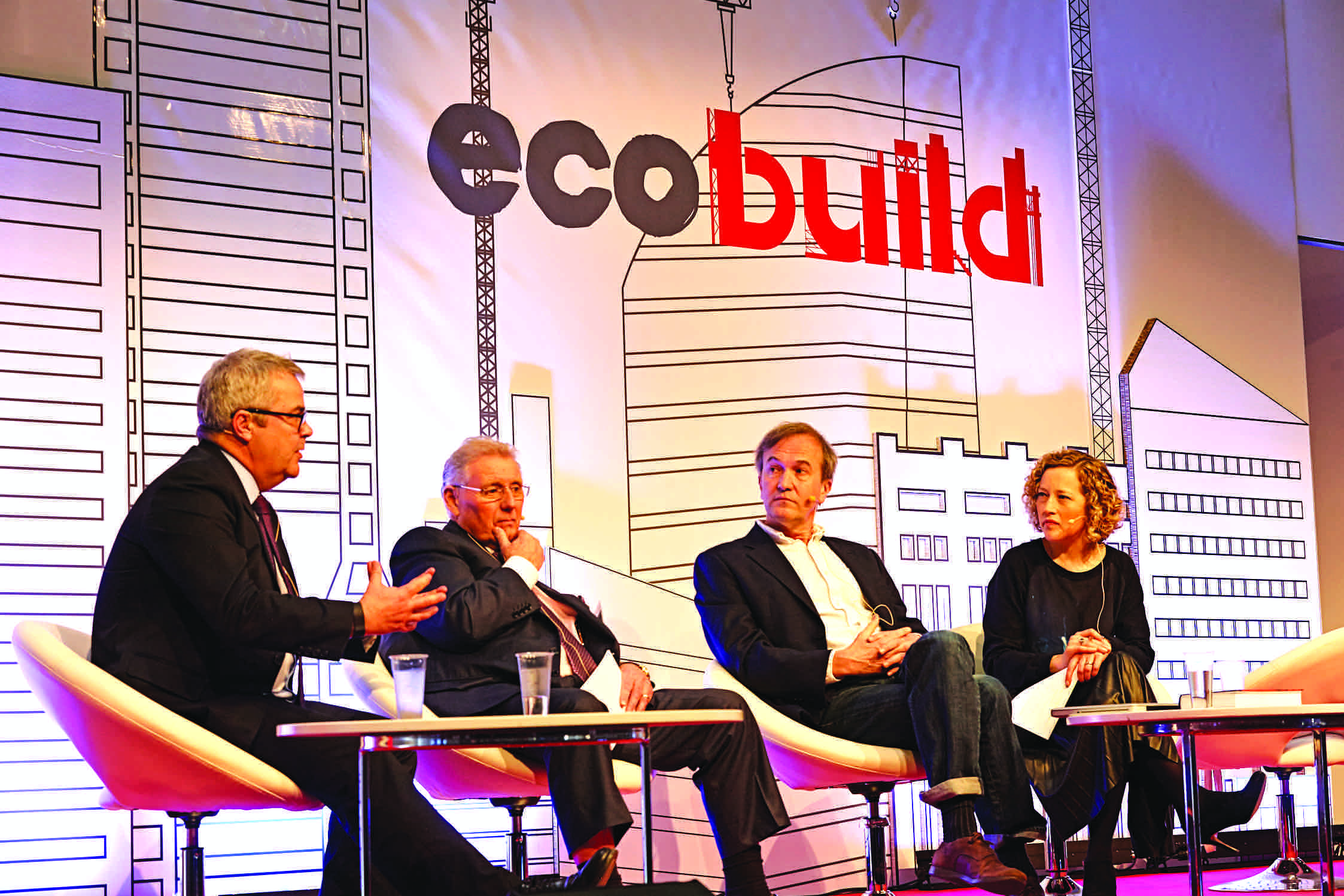

Special guests Stephen Fry and Will Gompertz, BBC arts editor

De Kestelier said: ‘The vision is that we will have one million people on Mars in the next century. These are techniques and materials we are testing now – it is reality.’

While the Mars project fired the imagination of Ecobuild delegates, other presentations reminded them that there is still plenty of work to do to improve building stock on planet Earth. In the wake of the poor results from the Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) programme (see page 27), many speakers lamented the performance of UK building stock.

In a seminar hosted by the Better Buildings Partnership, new research presented by Verco technical director, Robert Cohen, mirrored the BPE results. It found that commercial buildings in London were using two to four times more energy than equivalent offices in Melbourne.

Cohen described how the Nabers mandatory energy rating scheme had improved the performance of commercial buildings in Australia. He said the UK and Europe could not adopt the same system because they lacked the essential requirements of Nabers, such as: a definition of a base building; an investment-grade measurement standard; a consumer rating system; or a requirement to disclose performance on sale or let. ‘Design for performance requires a deep culture change in the UK and Europe,’ Cohen said.

Chris Tinker, executive board director and regeneration chairman at Crest Nicholson Regeneration, recalled systems that had not worked properly on their schemes. ‘The reality is that delivering low carbon energy has unintended consequences,’ he said.

HS2 design lead Sadie Morgan addresses the conference

Tinker described how, on one scheme, residents ran the system on full and opened windows when it got too hot. ‘The system is designed for low energy, but consumes more energy because of how we behave, not because of how they are delivered.’

Arup associate director Barry Austin highlighted the unmanageable complexity of some buildings, with controls fighting each other to cool and heat buildings.

‘In every problem building we go into, controls are the issue,’ he said. ‘It’s a case of going through them systematically, but it can make huge improvements.’

Austin added that use-of-building data would help create feedback, but intuitive interfaces had to be designed for people running buildings. It was, ‘a nut that the industry had yet to crack’, he said.

Jon Bootland, Passivhaus Trust CEO, said the performance gap is an issue not just with energy, but also for environmental and thermal comfort.

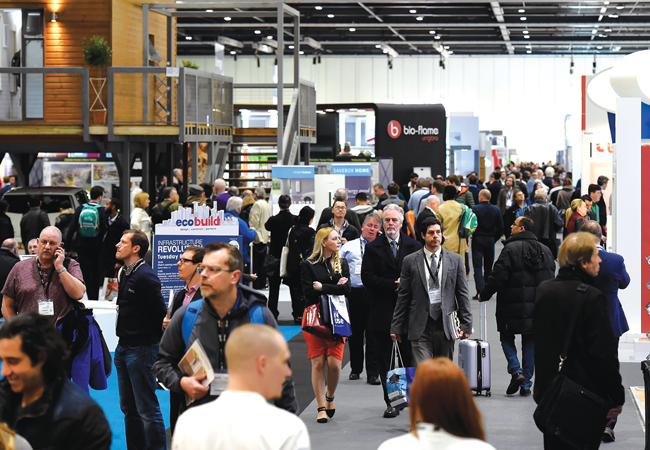

Delegates applaud a speaker at Ecobuild

He believes the main driver to change the housing model is the forecast increase in heat-related deaths because of climate change and an ageing population – from 2,000 to 7,000 per year by the 2050s. (See panel ‘Why overheating is a hot topic’).

Bootland said retrofit works to solve such problems could cost between £17,000 and £30,000 per dwelling.

A session on the Bonfield Review suggested a system of standards and enforcement for the retrofitting of housing would be recommended to government by the summer. The review is expected to play a key role in informing green housing policy that would overhaul the UK’s existing housing stock.

Review chair and BRE chief executive, Peter Bonfield, said they wanted to create standards and an enforcement regime that would ‘build trust and confidence in the way energy efficiency measures and renewables are put in place.’ (See panel, ‘Every Home Matters’).

Every home matters

A presentation on the recommendations of the upcoming Bonfield review, officially known as Every Home Matters, gave an insight into the standards and guidance that government might implement to improve the energy performance of existing homes.

Liz Male, who chaired a skills and training stream, said there needed to be a holistic approach to low energy homes and said an ‘underpinning knowledge and understanding of basic building physics’ was required. There was a knowledge gap in assessment, design, installation and supervision of low-energy homes, she added, and a training and accreditation system would be put in place to ensure consumers could choose from a list of competent certified companies. The review will also recommend a certification system for products, and a Code of Practice for firms.

Bonfield said the new system would establish one place for consumers to find out more about their home. ‘Enough is enough,’ he said. ‘We’re going to take responsibility for delivering measures we will be proud of in the future.’

There were plenty of encouraging signs of organisations getting to grips with building performance at Ecobuild.

Delegates at a session on the Mayor of London’s RE:FIT energy efficient initiative heard that, since 2009, £93m had been saved across 607 buildings.

The programme guarantees cost savings of around 28% for public sector organisations, thanks to an energy performance contract framework for suppliers. A programme delivery unit ensures support throughout the lifetime of a project, including the leveraging of funding. The scheme is now being rolled out across the UK. ‘There’s a lot of money out there to help you pursue energy efficiency,’ says Richard McWilliams, director at Turner & Townsend, the programme’s delivery unit manager.

Accurate operational data is essential to verify the savings being made. ‘If EsCOs [energy service companies] don’t achieve those savings, they have to offer a refund, or put in measures at their cost,’ said McWilliams.

An excellent case study for which data monitoring was key is the Crown Estate’s 7 Air Street office development in the West End.

Jane Wakiwaka, sustainability manager at the Crown Estate, said: ‘We pay for soft landings as we believe it’s necessary to ensure the building functions properly, and the occupiers remain happy.’ The £7,000 savings per floor, compared to a building that just complies with regulations, has helped ensure the Air Street office has been 92% let since its completion in October, said Wakiwaka.

An Edge debate, chaired by former chief construction adviser to the government, Paul Morrell, heard thoughts from various industry representatives on how the performance gap could be closed.

Why overheating is a hot topic

Speakers in a session on overheating cited many examples of problem housing.

Paul Ciniglio, sustainability and asset strategist at First Wessex Housing Association, said that as many as 20% of new homes in the UK are suffering from overheating and uncomfortable temperatures.

He said the company had spent £50,000 on insulating heating pipework to try to combat overheating problems in two blocks of flats. ‘That should have been right at the design stage – it’s too late once the homes are built.’

‘We cannot adapt to changing temperatures very quickly, so it’s a bigger issue for us than for people in the Mediterranean.’

Nicola O’Connor, from the Zero Carbon Hub, said she never once thought to complain to the landlord when her London flat was overheating. ‘It’s this mindset we need to tackle; overheating is a problem that’s as important as a broken boiler.’

The Zero Carbon Hub found that 20% of dwellings are overheating – so the vast majority of buildings are not. ‘But as the climate changes – and as we continue to build in dense cities – this problem is going to grow,’ O’Connor said.

Nick Grant, principal of Elemental Solutions, said, as UK residents, ‘we are not programmed to think that it’s ever going to get hot’.

Tom McNeil, an engineer at Max Fordham, said: ‘If your modelling assumptions are unrealistic, your results will be unreliable, but there is no industry standard on modelling inputs for heat gains from lighting, occupancy and equipment.’

Alan Penn, dean of The Bartlett faculty of the built environment at University College London, said there should be a move to track performance and this could be incorporated into Building Regulations. ‘If firms had failed previously, this would impact on whether their future projects would meet regulations,’ he said.

Lynne Ceeney, project manager at UKGBC, suggested industry should aim towards ISO process standards rather than energy targets. The panel concluded that a Nabers-style ratings scheme should be considered in the UK. Wilmott Dixon’s technical director, David Adams, said the contractor could work with performance targets. ‘I’m keen. If you want outcome performance, ask for it. We have an industry to turn around and, in my opinion, the way to do it is to focus on outcomes.’