Nuclear physicist Niels Bohr once said that ‘prediction is very difficult, especially about the future’. On the evening of 23 June, few readers of the Journal would have predicted that there would be a new Prime Minister before the summer recess, let alone that it would be Theresa May. After a turbulent month in British politics, that is precisely what the UK has. But what might it mean for readers?

The legal challenges

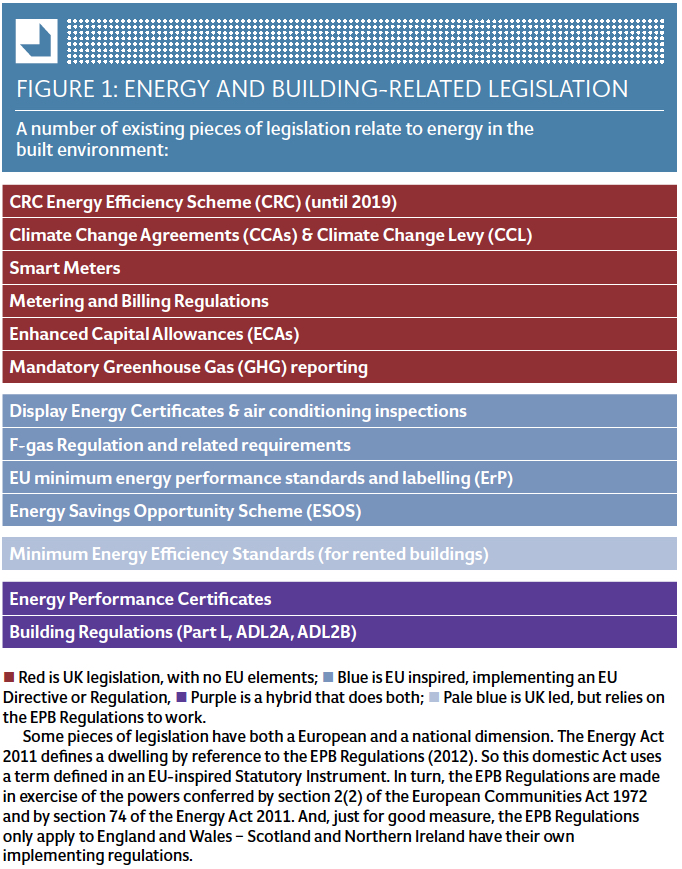

It has been suggested that there are some 40,000 individual items of legislation affected by the decision to leave. So the legal consequences of the UK exit are complex, especially in the area of environmental legislation and energy management law. Many principles and legal obligations in the UK, Scotland or England and Wales, or devolved law, stem from EU legislation.

There are European regulations that have a direct effect in UK law under the provisions of the European Communities Act. Then there are Directives, such as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), which are implemented individually by each member state – and in the UK there may be devolved implementation in Scotland and Northern Ireland, as with the EPBD. To add to the complexity, the EPBD is implemented in England and Wales in two separate sets of regulations – the Building Regulations and the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPB) Regulations.

Figure 1 shows how intertwined is legislation in Europe and England and Wales. It demonstrates the scale of the challenge facing David Davis and his new ‘Department for Brexit’. In England and Wales the EPBD is implemented through the EPB Regulations and Building Regulations. Detailed implementation of Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards uses the EPB Regulations and the Energy Act. Unpicking these will be a major task.

The Climate Change Act and Brexit

The Climate Change Act (2008) legislates for the UK to reduce emissions by 2050 by at least 80%, compared with 1990 levels. This is done through a series of statutory five-yearly carbon budgets, which are designed to represent the lowest-cost path in which the UK can contribute to global efforts to tackle climate change. The Act requires the government to set out its policies to meet the targets, and these will now also need to reflect the UK’s changing relationship with the EU, although any serious ambition to deliver on the targets excludes the option of a bonfire of EU energy and environmental legislation.

As far as F-Gas emissions are concerned, it is worth noting that the UK is a signatory to the 1986 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer so is not affected by Brexit.

On 30 June the government committed to the emissions reductions recommended by the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) for the fifth carbon budget 2028-2032, which will reduce UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 by 57%, relative to 1990 levels. On that day the CCC also published its 2016 Progress Report to Parliament, detailing how the UK is doing in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and meeting carbon budgets.

The report shows that UK emissions have fallen by an average of 4.5% per year in the last three years, and are 38% below 1990 levels. It identifies a gap of approximately 100 MtCO2e between the likely reductions from current plans and the reductions required by the fifth carbon budget for emissions in 2028-2032.

The government has recognised this policy shortfall and has committed to come up with an ‘emissions reduction plan’ later this year. The Progress Report sets out several areas that it expects this plan to address, including: decarbonising of heat; improving energy efficiency; a new approach to the development of carbon capture and storage; and mature low carbon generation.

Given the analysis by the CCC, it seems clear that unpicking the EPB Regulations and the parent Directive is the wrong answer for the climate, so there is an argument for leaving alone and incorporating these requirements fully into UK law. More correctly, this means incorporating them into England and Wales law for the EPB Regulations, and English law for the Building Regulations, as other regulations apply in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. This represents another legal complexity of the exercise.

Review of energy requirements of Building Regulations

Under the EPBD, this is meant to happen in 2017. There may be some debate about whether or not it goes ahead. However, some readers may recall that before Brexit there was an argument between the Commons and the Lords over the upper house’s attempt to reinstate a zero carbon homes requirement into law.

It ended with an agreement to drop it, in return for an undertaking to review the energy efficiency elements of the Building Regulations. It is not clear whether all parties to the deal realised that, under the EPBD, that review was required in 2017 anyway, so it was a free hit for government to offer.

It seems unlikely that Brexit will lead to wholesale changes to existing UK legislation in these areas

However, post Brexit, with the status of the review under the EPBD in question, the deal now means that the review should go ahead, regardless of Brexit. We shall see, and, once again, it is different in Scotland, where it is more likely that there will be a review of Section 6 of the Scottish Building Standards.

Distributed generation

This is largely a domestic policy, with planning rules implementing requirements for heat networks and onsite generation – especially in urban areas – driving a transition to more efficient heating and cooling systems and networks.

UK planning policy is unlikely to change as a direct result of Brexit, although EU framework support and policy direction will be removed. The government is already reducing renewable generation subsidies, although the CCC has identified low carbon heating as an area requiring new policy measures.

Conclusion

The EU has undoubtedly played a key role in energy management in the built environment, setting targets and legislating to improve energy efficiency in buildings and products. For the reasons outlined above, it seems unlikely that Brexit will lead to wholesale changes to existing UK legislation in these areas.

As for the timing of Brexit, the UK must give notice under Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon, which kickstarts a period of two years for the UK to negotiate the terms of exit. Early indications are that Theresa May does not wish to give notice until the end of 2016, so it is most likely that the actual UK exit will be late in 2018.

- Hywel Davies is technical director at CIBSE