A 20-year civil war has wreaked havoc on the village farming communities of Uganda. Thousands of people lost their lives, millions lost their homes and almost all of the schools in rural areas were destroyed. Today, Ugandan children are left with no real hope of the education they so badly need and want. But things are set to change in Parabongo village, in the north of the country.

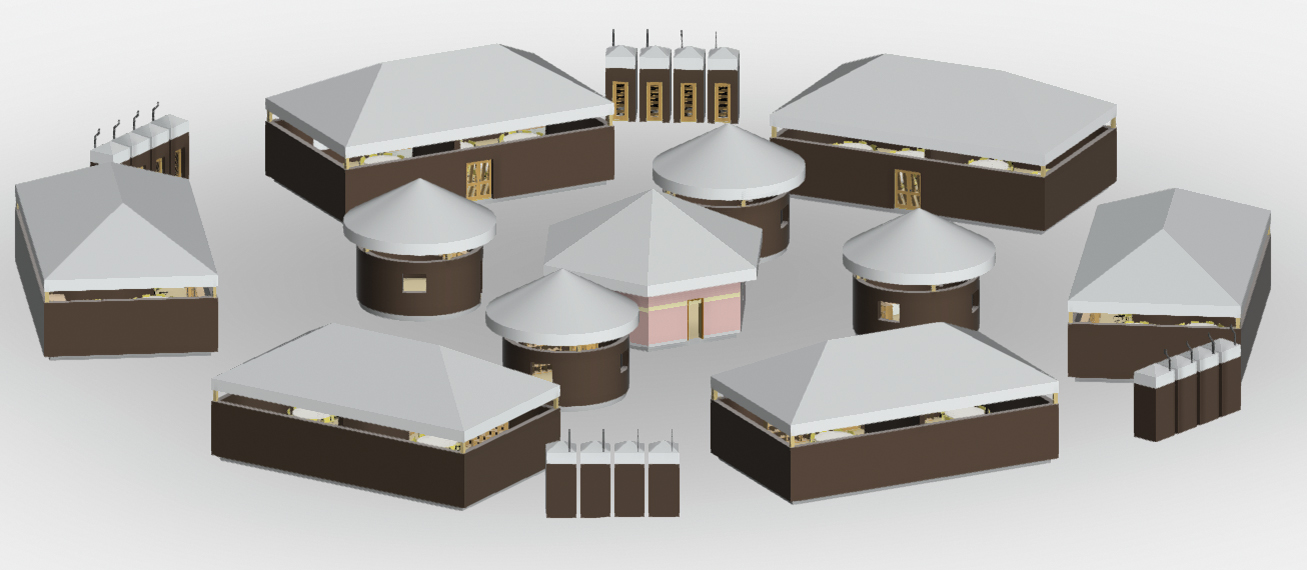

An impressive new school for more than 1,000 students has been planned. Its simple, elegant design consists of a series of classrooms arranged in concentric circles around a central assembly space, to help create a community of students; its scale and choice of materials have been chosen to reflect the local vernacular. The design even includes space for planting, to allow the school to grow food.

More impressive still is that the scheme was designed by a team of 13- and 14-year-old pupils from King Ecgbert School in Sheffield, under the Design Engineer Construct (DEC) learning programme – part of the Class of Your Own (Coyo) initiative. Coyo was founded by Alison Watson in 2009, to introduce studies on technical and professional elements of the built environment onto the school curriculum (See ‘A class of your own’, Education Facilities Special, CIBSE Journal, May 2014). The initiative has been gaining momentum ever since. Each year, as part of the DEC curriculum, Coyo sets students a challenge; in 2015 it was to design a new school for Parabongo.

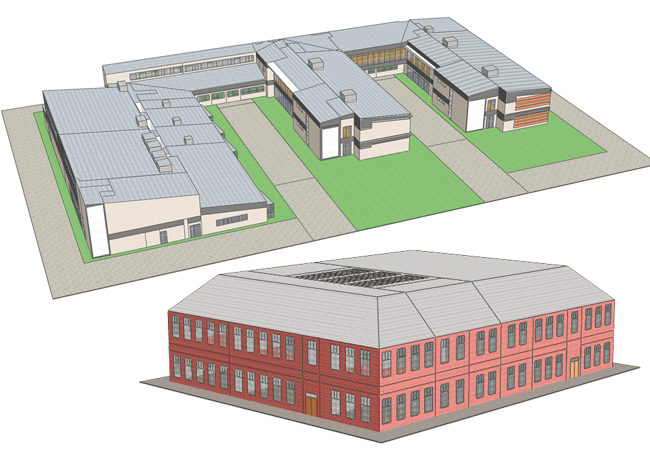

As part of the entry, the team modelled the design using Revit to create drawings, renders and walkthroughs

Watson says the idea for the challenge stemmed from the work Alison Hall, of charity Seeds for Development (www.seedsfordevelopment.org), had been doing in Parabongo to help ‘empower the local community to improve their lives to become socially and economically resilient’. The challenge brief was for a team of up to 10 students to design an accessible and sustainable school to accommodate 1,000 children aged between three and 18 years. It called on students to think about their selection of materials, to make the best use of those that are both readily available and easily adapted by a local workforce. It also suggested that architecture, civil and structural engineering, building services engineering, facilities management, quantity surveying, project management, interior design and landscape architecture should all be represented in developing the design solution.

‘It was logical that we launched this very special competition – the whole point of the Design Engineer Construct learning programme is to enable young people to lead on their own projects,’ says Watson.

The teams were given a detailed plan of the site, which had been prepared by Liverpool John Moores University with the support of Topcon Positioning Systems. Students were also encouraged to email questions about Ugandan life and schooling to Ronald, a 13-year-old pupil in Kampala.

A hexagonal building for assemblies is at the heart of King Ecgbert’s design for the school in Parabongo

The work that led to King Ecgbert’s winning entry started in July 2015, when Year 9 DEC students investigated the vernacular building styles of rural Uganda, the availability of materials, and climate data. ‘Students could pick the discipline in which they wanted to work, so those more interested in cultural aspects of design could focus on how the buildings should feel,’ says Helen Vardy, the school’s leader of learning, Key Stage 4 and 5 design and technology.

The research enabled the students to develop a concept design for the new village school and then to build a physical, 3D model of it in cardboard. At its heart, King Ecgbert School’s scheme is a large hexagonal school assembly building, which also functions as a large classroom and a space for students to eat lunch. Set out in a circle – around this hexagonal hub – are four smaller, circular buildings, their form developed to reflect traditional rural Ugandan homes. These are classrooms for younger children.

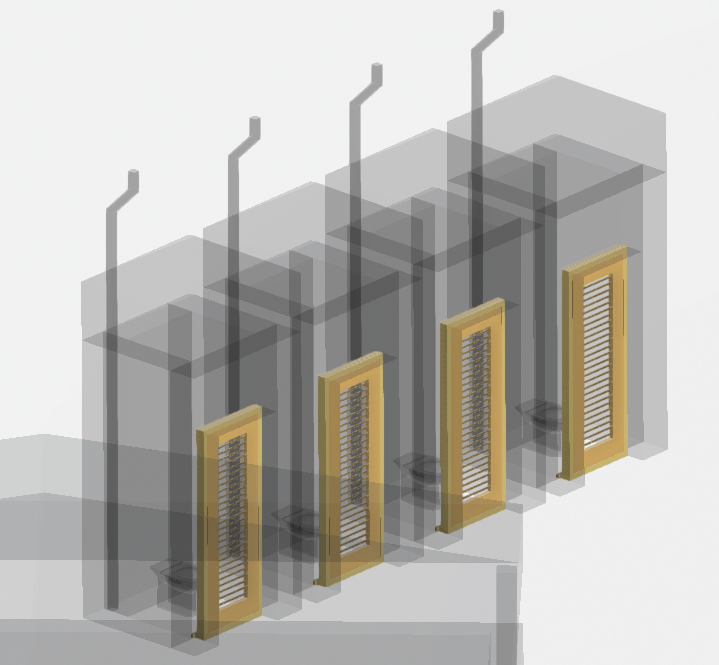

The design featured five blocks of twin-pit for pour-flush composting toilets

Surrounding the nursery classrooms is a second circle comprising six larger, rectangular buildings, each capable of housing two classes of 40 students. The designers hope this will give everyone ‘a chance to learn and talk to their teachers without being overshadowed by the sheer number of students in their class’.

On the outer perimeter of the school, spaced between the rectangular classroom blocks, are five blocks of four composting toilets. The students’ presentation explains that the concept is based on ‘twin-pit for pour-flush toilets’, as opposed to ‘ventilated improved pit (VIP) toilets’, because they are beneficial to the soil and ‘will be able to be used at all times, unlike the VIP toilets, which cannot be used when full or being emptied’. The students estimate a cost of £75 per toilet – £1,500 in total.

The scheme also includes a large kitchen block – set to one side of the site – and gardens for planting cassava, a crop grown locally for food.

The buildings are constructed from traditional materials, including unfired clay/straw brick walls, which will be made on site by the community, and straw roofs.

In February 2015, four Year 10 DEC students, working at lunchtimes and after school, set about reviewing the research and refining the concept. The team was: Jessica Chamberlain, architect and building services engineer; Jessica Mellor, project manager, civil engineer and facilities manager; Alex Wheatley, landscape architect and interior designer; and Katie Wilkinson, architectural technologist, structural engineer and quantity surveyor. They worked under the name Timu Matumaini – Swahili for Team Hope – which was chosen ‘to show what school and an education means to anyone who is given it’.

Children in Parabongo, Uganda

Vardy says the team worked well together: ‘They all seemed to fall into their roles naturally and were good at challenging one another.’ As part of the entry, the team produced a report, made a video (bit.ly/1R6W91v), and modelled the design using Revit to create drawings, renders and walkthroughs. The judges were impressed, describing the scheme as ‘an outstanding design’ and saying that the team ‘showed they had clearly thought through every aspect of the brief’.

Things really started to take off after King Ecgbert’s entry won the competition. The winning team visited Arup’s offices in London, where they met James Okumu, head teacher in waiting of Vision Hope School, who had been flown in from Uganda courtesy of Arup. ‘It was incredible meeting the principal and hearing what difference a school will make to the community,’ says Vardy, who added that Okumu was enthusiastic about the scheme. ‘He loved the design because he said “it gave the school a real sense of community because it is based around a circle”.’

Okumu also proposed some improvements, including teacher accommodation. ‘We’d not even considered that,’ says Vardy. ‘The suggestion helped highlight some of the cultural differences between what we’d assumed they needed and what they actually needed.’

The principal raised concerns that the blocks of toilets were too close to the classrooms and explained that the villagers were very concerned about fire in buildings – so the design team replaced the traditional grass roofs with a corrugated steel alternative. Arup then worked with them to incorporate these refinements into their design.

The site of the new school

The steel roofs had the advantage of being low cost and they could be used to collect rainwater. ‘They do have quite a bit of rain [in Uganda] and it does get incredibly hot,’ says Vardy. The roofs were lifted clear of the walls to allow air to enter the classrooms through low-level window openings, and to rise up and out from beneath the eaves. The team describe this solution as a ‘solar roof extraction system’, which they say makes ‘the perfect atmosphere for learning minds’. And because the school doesn’t have access to electricity, the students suggested the roofs could also be used to support solar panels.

Quantities of materials needed were calculated by the team, working with BAM, and a cost to build the scheme was estimated at £150,000, including getting experts out to Uganda to help local people construct the project. The final element of the design was a visit to Arup’s Sheffield office – the school’s DEC sponsor – to finalise the team’s digital model.

Participating in the project has been a valuable experience: ‘The students learned how powerful buildings can be and what a difference they can make – it’s beyond architecture,’ says Vardy. ‘It has also been hugely beneficial for the students to take on real-life roles and to work on a real brief; it has given them an insight into working as a team’.

For Coyo’s Watson, the task now is to realise King Ecgbert’s design; ‘We’re trying hard to raise money to get the school built,’ she says. A crowdfunding initiative was launched in March with the help of CIBSE Yorkshire, to raise the capital needed. Depending on how well the funding goes, the pupils may even get the opportunity to fly to Uganda to see their scheme realised. CJ

- For more information about the DEC module visit the Design Engineer Construct website

- To donate to the project, vitit the crowdfunding page