To safeguard against catastrophic climate change we need all new buildings to be net zero energy (NZE) by 2030. We need a radical shift in what is seen as a successful building, focusing on human-centred design. We need performance-based policy that uses metrics to drive NZE. As engineers, let’s work together and make the UK a centre of excellence for NZE. As a first priority, let’s fix London’s broken carbon policy.

In June 2016, the World Green Building Council launched its global ‘advancing net zero programme’, targeting all new buildings to be NZE by 2030, and every building by 2050.1 This will involve a radical shift in how we approach the design of new buildings, and how we deliver large-scale retrofit programmes.

All new developments and district heating schemes need to be zero emissions ready

Current building regulations lack integrity, and their application within the planning process forces design teams to submit evidence that is dishonest and without rigour. The meaning of zero carbon in the UK has been diluted by successive attempts to create a definition that was palatable to powerful lobbies. Since the government scrapped the Code For Sustainable Homes, there is no longer a recognised standard that encourages buildings to exceed current regulations.

London is often regarded as atypical, allowed to set its own carbon targets, while this freedom was removed elsewhere. Today, all new London homes are described as zero carbon, yet they only need to achieve a 35% reduction in regulated carbon emissions – emissions associated with heating, ventilation and lighting – compared with current building regulations. The remaining regulated carbon emissions can be ‘offset’ through cash-in-lieu contributions to the relevant London borough.

First priority: Fixing London’s broken carbon policy

London has set a citywide CO2 emissions reduction target of 60% by 2025, relative to 1990 levels. We are currently not on track, exacerbated by the fact that the current London Plan is now a barrier to net zero energy development. Under current policy, new buildings need to achieve 35% carbon emission reductions compared with a Building Regulations baseline.

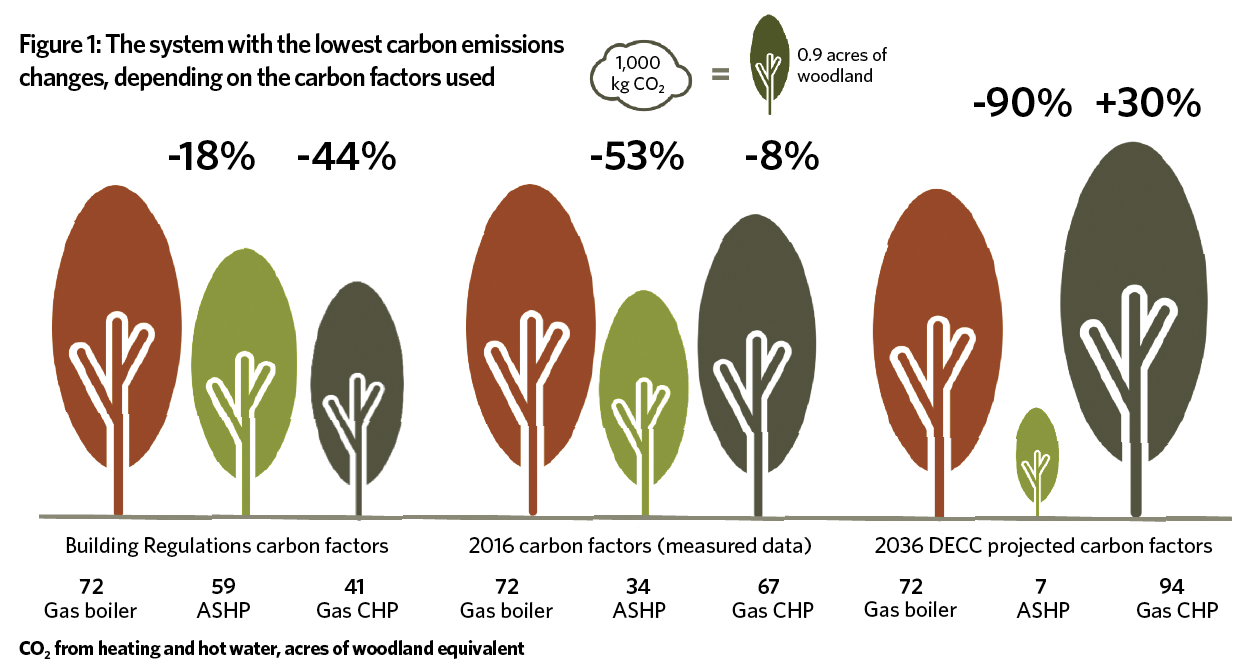

Outdated carbon factors are used when carbon emissions are calculated against these planning requirements. This has the effect that fossil fuel-powered hot water generation – that is, combined heat and power (CHP) – is preferred, which appears to have lower carbon emissions than electricity-driven hot water generation through air source heat pumps (ASHP) (see Figure 1). Additionally, developments are obliged to connect to fossil-fuelled district heating schemes, thanks to the position of district heating in the London Plan ‘energy hierarchy’, even if the alternative is 100% renewable.

The London Plan is being updated this year and Elementa Consulting invites you to join a cross-sector initiative to develop concrete recommendations for a new energy and carbon policy for London. Contact clara.bg@elementaconsulting.com for more information, and if you would like to be involved.

While the intent is positive, London’s policies perpetuate ‘business as usual’ thinking, and lock design teams into specifying systems that they know are working in the wrong direction – away from net zero.

In his keynote address at the CIBSE awards in February 2017, Dr Pawel Wargocki highlighted that our primary reason for constructing buildings is not to reduce carbon emissions, but to create inspiring, nurturing places for people. NZE design tackles this conflict head on – it offers us both.

I believe we need to shift our thinking towards human-centred design, creating culturally rich, socially just and inspiring places that enhance our wellbeing. Our definition of success needs to shift from a building that performs slightly ‘less bad’, to one that regenerates its environment. A key measure of success has to be buildings that are fossil fuel free, powered by renewables and whose embodied energy impacts are offset.

Real-life working examples exist, many using the Living Building Challenge2 as their framework. The past two winners of International Project of the Year at the CIBSE Building Performance Awards are among them – the David and Lucile Packard Foundation headquarters in California, and DPR Construction’s NZE office in San Francisco.

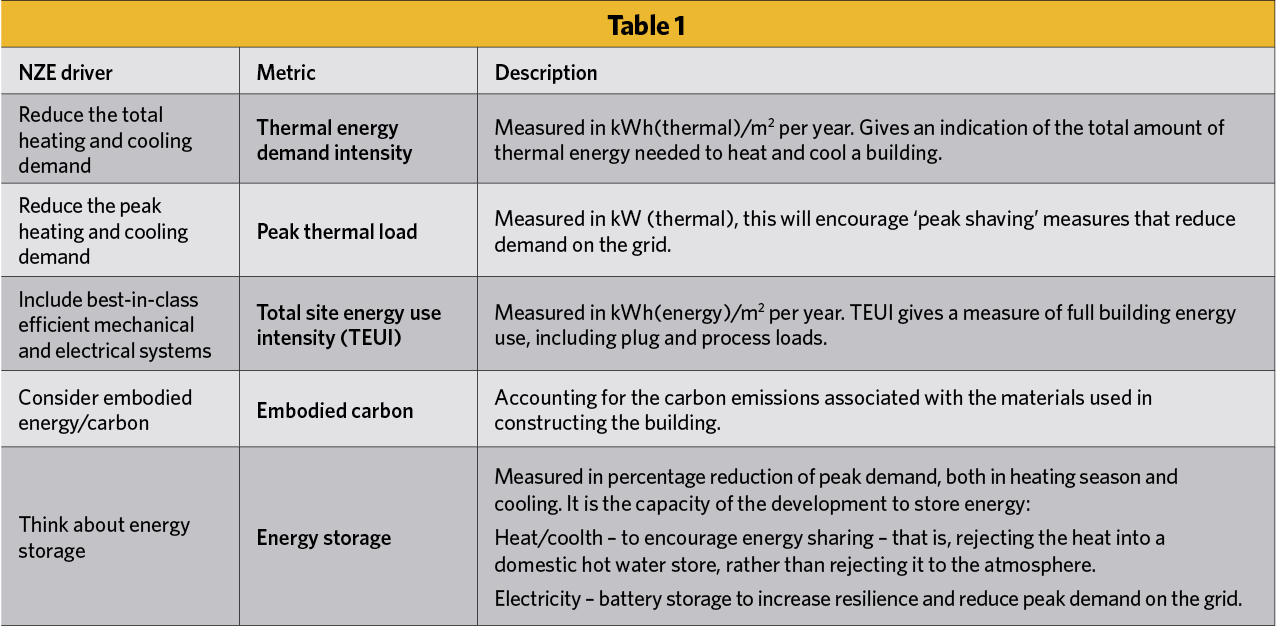

To drive NZE design, policy needs to be based on broader performance metrics, as shown in Table 1. Currently, the only metric that is used is CO2/m2 using out-of-date emissions factors. On its own, this doesn’t always direct us to effective design choices.

For buildings to reach zero emissions, we also need investment in renewables to supply 100% of their energy. It is not essential that all buildings achieve this today, but it is fundamental that energy demand is reduced in line with NZE metrics (see Table 1). When the grid becomes further decarbonised, the energy that is consumed will eventually be emissions free. Investment in renewables and grid storage is therefore a prerequisite for success.

All new developments and district heating schemes need to be ‘zero emissions ready’, with a plan showing how to achieve combustion-free NZE buildings (regulated and unregulated) without costly retrofitting of building fabrics and services.

The C40 cities’ report (Urban Efficiency II)3 highlighted that ‘policy mixes’ and the use of complementary strategies and incentives across various programmes are crucial to achieving required targets. To drive an actual reduction in carbon emissions, widespread post-occupancy evaluation, increased research and education into NZE performance, and incentives to drive change are also required.

The NZE framework is honest because: it includes all energy (regulated and unregulated); works with integrity, being based on actual measured performance; and is rigorous, as ‘zero means zero’. It is fully aligned with the ethical principles of the Royal Academy of Engineering, and with the CIBSE code of conduct, which seeks to ‘promote the principles of sustainability and to prevent the avoidable, adverse impact on the environment and society’.

We have an opportunity to make the UK a centre of excellence for NZE design and construction, and building services engineers must be at the forefront of this seismic shift in thinking.

- The Rising Star Award, launched in 2013, promotes people who have made a difference to the sustainability agenda

References:

- WorldGBC launches groundbreaking project to ensure all buildings are ‘net zero’ by 2050. (5 March, 2017).

- International Living Future Institute, Living Building Challenge: A visionary path to a regenerative future

- Urban Efficiency II: Seven innovative city programs for existing building energy efficiency, a report by C40 Cities

- Integral Group and Pinna Sustainability and British Columbia Office of Housing and Construction Standards (2016), Stretch Code Implementation Working Group: Energy step code implementation recommendations

- The London Assembly Environment committee, Cutting carbon in London – 2015 Update

Clara Bagenal George is an environmental design engineer at Elementa Consulting.