Imagine a workplace with a combination of quiet space, meeting rooms and ad-hoc community areas. Now imagine going to work and choosing a place to sit that suits the activity you need to do that day.

The philosophy behind this nomadic employment style, known as agile – or activity-based – working, is that, when people are able to choose where to sit, they structure their days more productively. Unlike ‘hoteling’ – where workers can reserve workstations in advance – or ‘hot desking’, where they can sit at any available desk, agile working is not necessarily a space-saving solution.

‘If you employ agile working, you can avoid having empty desks, but it does not mean you have less space – you just use it more efficiently,’ says Elinor Huggett, sustainability adviser at the UK Green Building Council (UK-GBC). ‘Agile working isn’t for every organisation, but – where it does work – we believe it has a positive impact.’A gleaming example of this is Sky Central’s new HQ, in London, where building services have been designed to agile working principles by engineer Arup.

In its recent report, Wellbeing lab: offices – a compendium of experience, the UK-GBC highlighted office layout and better control as factors that influence human health and environmental sustainability.

Over the past eight months, the UK-GBC canvassed its members – including Max Fordham and BuroHappold Engineering – on the ‘quick wins’ they have made as a result of the Wellbeing Lab programme. They suggested: zoning space, to allow for quiet areas and collaborative areas; creating new types of workspaces, to reduce time spent at individual desks; and including recommendations in fit-out guides to help tenants maximise the effectiveness of their space.

Effective use of space – and giving people the autonomy to work how, and where, they want, can be beneficial for employees. But flexible spaces mean variable occupancies, so building services engineers have to ensure lighting, ventilation, cooling and heating are responsive, with excellent occupant control.

Agile pros

Arup associate Vasilis Maroulas says agile environments will work alongside wellbeing principles that are already gaining momentum in the industry.

‘Agile spaces ensure flexibility and cost-effectiveness because more people can be accommodated at fewer desks.’ he says. ‘This requires spaces that are easily adaptable, with responsive systems, which can create healthier environments through better control, suitable lighting levels, and better indoor environmental conditions.’

In addition to wellbeing and social benefits, Maroulas says the key advantage of agile working is the ability to adapt to individual needs and activity-based requirements.

‘Having a nice place to work increases productivity and adds spatial efficiencies, so spaces could be reprogrammed for other uses or translated into economic savings.’

Henry Pelly, sustainability consultant at Max Fordham, says a balance must be struck between agile working spaces and giving people their own territory. ‘If anyone can sit anywhere, their choice is reduced because – if the place they like to sit is gone – they are left with fewer options.’

He says a desk manages things you cannot hold in your head. ‘Reducing space – and, therefore, reducing cost – is a narrow way of looking at the financial implications of agile working. By removing desks, you remove personal territory, reducing staff motivation.’

Pelly adds that turnover and motivation are intrinsically linked, and taking away things that employees need might cost more in the long run. People do different tasks during the day, so employers should offer spaces for them to do that more efficiently, but they also need a base as an ‘extension of their memory’. He says the relationship between the work people do and the space available for them to do it can motivate staff to work.

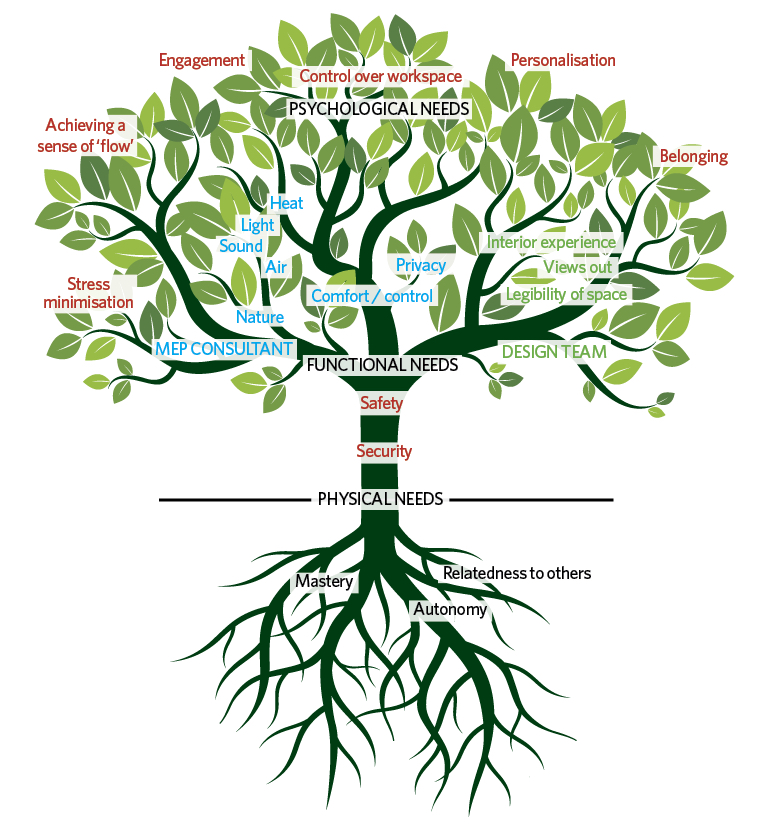

Pelly, an environmental psychologist, has helped develop an approach that allows space to stimulate work (see Figure 1). The tree roots are the fundamental attributes of intrinsically motivating work; if these aren’t cultivated, improving the physical environment won’t make work better, he says.

Figure 1: Organisational culture and job design

The trunk is the need for basic physical comfort, and the branches are the key factors in functional comfort – the elements that need to be addressed for a workplace to be physically optimised. ‘If all these factors are robust, you have the ingredients for psychological comfort that allow people to flourish at work,’ says Pelly.

Max Fordham, which has been refurbishing its London office over the past three years – including consultation – has incorporated a range of spaces to support the variety of work its staff do. This includes areas for collaboration, six solitary working desks, and a library on the third floor for doing cognitively difficult work.

The firm has reduced the amount of individual space, but it still gives most people their own desk, as well as a variety of additional areas to support other kinds of work. It is also switching desktop computers for laptops, so people can move around the office easily.

Trevor Keeling, senior engineer at BuroHappold Engineering, says different spaces – such as a whispery library or a lively breakout area – send contrasting signals to users, and prompt people to think in alternative ways. ‘A quiet space prompts focused work, while a conference environment is better for collaborative work, because it encourages different behaviours,’ he says.

All of these spaces have different requirements for environmental conditions, adds Maroulas. ‘An active brainstorming session will need good daylighting and infrastructure provision, but could have forgiving comfort conditions. If you’re on your own in a space, having the right indoor environment is critical. Lighting could be reduced in the ambient open-plan space, while meeting the lux requirements in the workplane, enhancing wellbeing and saving energy,’ he says.

A challenge

Designing a single system with the adaptability that flexible working environments require is a challenge. ‘Different activities require different lighting levels, temperatures and infrastructure support,’ says Maroulas, who adds that overloading systems and occupants with controls is not a panacea.

Another consideration is creating environments that can be adapted to accommodate future developments in technology. ‘The rate of change in our digital era is phenomenal – the meeting room of today is nowhere near the meeting room of tomorrow,’ says Maroulas. ‘The question is, how do we provide the infrastructure today, so that – in future – the same space would be able to accommodate advances in digital technology?’

This rate of advancement is the biggest challenge for creating flexible spaces, says Maroulas. Another issue is noise and distraction control.

Keeling says agile workspaces renegotiate the trade-off between interaction and privacy, improving both by offering a variety of spaces that can be used for either private work or collaborative endeavours.

This method of working makes it easy for employees to leave their desk to make phone calls and to have small meetings. Combined with specially designed furniture – such as booths with acoustic buffering – this results in less noise and disturbance for those who are working on their own. Agile spaces also offer somewhere else for people to go to work when required. ‘This not only allows people to avoid sources of distraction, but also sends a clear signal that they do not wish to be disturbed,’ says Keeling.

When comparing three office types – agile, open-plan and cellular – Keeling found that agile working combined the best parts of cellular (privacy) and open-plan offices (collaboration), giving the user the means to choose what’s best for them at any given time.’

When working at a static desk, staff can be easily distracted. ‘But if you have chosen to work on your own in a particular location, you are signalling that you don’t want to be disturbed. It is as much about sending that “do not disturb” message as having an environment that’s better for doing that work,’ says Keeling.

For BuroHappold, employing agile-working principles is a test bed. ‘We are monitoring things such as noise and air quality using sensors in different locations. People are responding about their preferences – whether it’s too noisy or too stuffy – and this could be used to identify areas that are naturally more or less noisy, so tailoring agile design to how the building already works.’

The Sky’s the limit

In practice, agile spaces take a lot of planning; the concept for the new Sky Central building, at Osterley, London, was mooted 10 years ago.

Broadcaster Sky wanted to create a unique, activity-based workplace that would be responsive, inspiring, intuitive and amenity-rich for 3,500 people, catering to Sky’s fast-paced way of working.

Architects Amanda Levete and PLP and building engineer Arup responded to the brief by creating a three-storey, deep-plan ‘horizontal tower’ that would maximise opportunities for colleagues to meet and interact, but avoid the constraints of traditional high-rises. In fact, if Sky Central was a standard city-centre tower block, it would be 40 storeys tall.

Agile lighting

Sky Central is the main building on the media company’s west London campus. With 30-40% glazing around its perimeter – which allows daylight to penetrate 7-8m into the perimeter of the floorplate – the building is predominantly top-lit.

An array of roof skylights bring light into the top floor, while several atria in key locations draw light into the ground and first floors. This ensures daylight is available throughout the building, enhanced by its tall, floor-to-ceiling heights, ranging from 4.5m at the ground and first floors to 5.5m on the top floor.

Employees have the choice to work in a space with more daylight – directly under the skylight – or in an area with more ambient, artificial light. The average ambient light levels across the floorplate are 300 lux, and occupants at workstations can boost levels to 400-500 lux using personal desk lamps. When there is sufficient daylighting, the artificial lighting switches off automatically.

Maroulas says: ‘Having better control of their surrounding working environment aids occupant wellbeing, and feeds into the agile and wellbeing design principles.’

Maroulas says getting design decisions about air and light correct at the beginning of the project was paramount. Arup’s approach was to bring in light from the top, and air from the floor of the 170x70m building.

The building – which is divided into 18 ventilation zones to serve multiple ‘neighbourhoods’ – was originally designed for 2,700, but had the flexibility to cater for more than 3,500 occupants. Comprising a wide variety of space types – from desks, booths with partitions to offer attenuation from the ambient indoor noise, and secluded spaces where people can retreat from chatter – the building supports the full range of activities that Sky staff engage in every day.

To ensure adequate – and responsive – ventilation, an underfloor displacement ventilation system was installed. Air is fed out of floor diffusers at relatively high supply air temperatures – 19-21oC – and low velocity to avoid discomfort and cold draughts, displacing the existing warm, contaminated air and entraining heat from surrounding heat sources. The floor diffusers, operating in displacement mode, are connected to a pressurised floor plenum, which is fed by six risers, strategically located in the floorplate.

To ensure the system is responsive to the constantly changing space, the building services managers can lift up any 600x600mm floor tile with an inbuilt grille and move it to another location. No ductwork is connected to the diffusers, so their layout can be altered easily to suit any modifications in furniture, meeting rooms or desk positioning.

Maroulas says this approach was tested five years ago on The Hub – a 7,000m2 building on the Sky Central site. ‘We had to run extensive CFD modelling and testing to ensure something like that could work effectively. When we were sure it could, we scaled up from a small prototype to a 46,000m2 building.’

Sensors throughout Sky Central ensure uniform temperature in the large floorplate. ‘We are very reliant on having a delta T of 3K and low velocities to ensure we do not have large variability in temperatures,’ says Maroulas. Within the first nine months of operation, Sky Central reached its peak occupancy of 3,500 people and, so far, no complaints of cold or hot spaces have been lodged, he adds.

With an 80% average desk occupancy over one week – and an average density of 8-9m2 per person – CO2 sensors help to control the amount of fresh air coming into the space. In free-cooling mode, during the mild season, fresh air is brought through the air handling units directly from outside, reducing the refrigeration required to cool the air.

Project team

Building concept: AL_A

Executive architect: PLP

Engineer: Arup

Contractor: Mace

Workplace design: Hassell

The tall, floor-to-ceiling heights mean a reservoir of ‘used’, warmer air at higher-than-occupant level rises – via the process of stratification – through the atria to the top floor, and is removed via extract points integrated into six infrastructure cores. Typically, the stale air is extracted naturally from March to June, and from September to November, almost halving the energy consumption of the ventilation system during those periods.

Although productivity is yet to be measured at Sky Central, Maroulas believes the responsive services designed around agile working are creating better indoor environmental conditions for occupants.

Even placing staircases in prominent locations – and hiding lifts away from entrances – fosters a more agile and collaborative environment, while promoting a healthier lifestyle, he says.

‘As engineers, we are in the perfect position to instigate wellbeing choices through our designs.’