Building information modelling (BIM) – and especially BIM Level 2 – has been the catchphrase for new and more efficient ways of working in construction since the government mandate started in 2011. It was referred to as a BIM ‘level’ because the idea was to carry on making the process better and more efficient.

The BIM acronym, however, has taken on a bit of a specialised meaning in recent years. As a result, the work going on to define what the next iteration will be has dropped the moniker and, instead, is using the phrase Digital Built Britain (DBB).

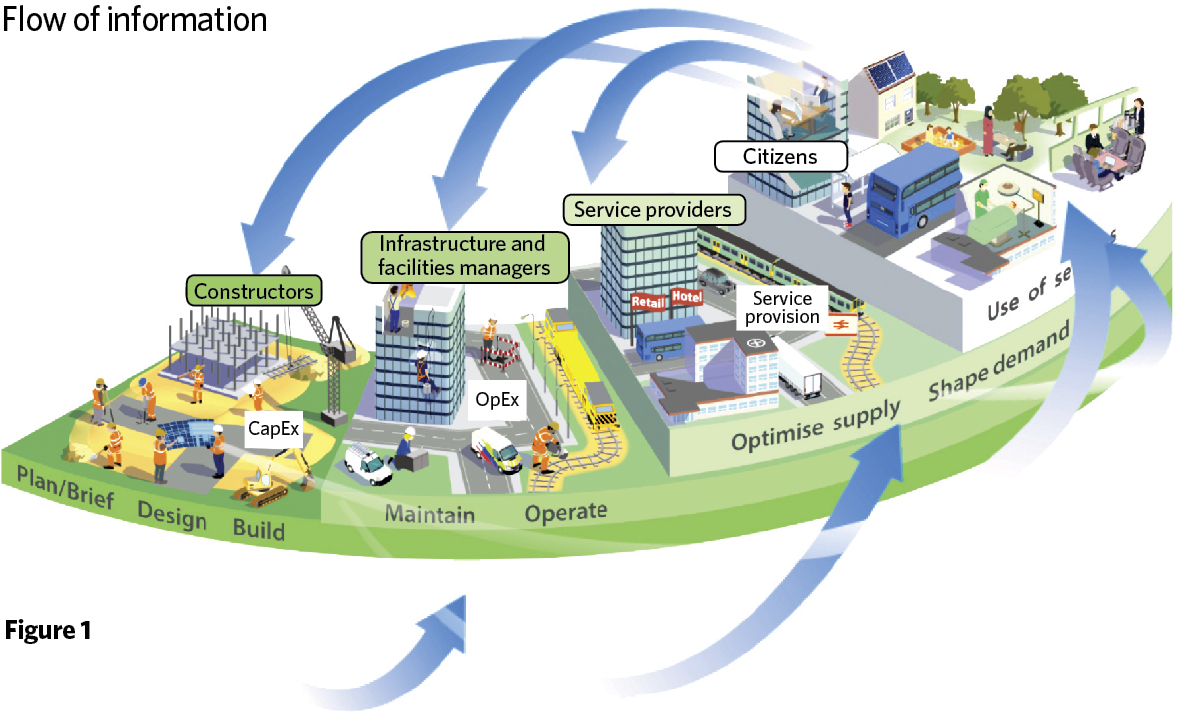

That’s all well and good, but what does DBB mean to people who work in construction? Right now, no-one knows the exact answer to that question – the processes are still being defined – but the basic concepts can be seen in Figure 1. Let’s have a look at what that might mean for us in building services.

Generally speaking, BIM Level 2 focuses on design and construction processes, standardising the approach and levelling the playing field for allcomers. It is the starting block for what will come next, which will have a much wider remit and look more closely at built assets in operation – how they interact with people and offer them digital services.

A workshop, hosted by the University of Cambridge in early April, invited practitioners and academics to start fleshing out what processes and projects could be run to make the ambitions of DBB a reality. It was an exhausting two days of intense thought and information exchange – and from these discussions came a bewildering array of possible projects and research ideas. We rationalised these into functional groups and voted for the ones we thought would best serve our industry.

High on the list of topics discussed was harnessing sensors to offer far more than building controls. What would happen, for example, if we made data available from a multitude of built assets – about how they are functioning, where people are, what energy they are using and what energy they could be harvesting? Could we start to understand what triggers are causing spikes in energy demand, and ramp up other energy sources to balance the loads? What would be the security implications of doing that? Who would look after the data and how do we democratise it?

Our challenge is to offer the spine through which data can travel into and out of projects

All big questions, but some of the answers are even bigger. We could employ built assets as energy stores, to mitigate spikes in demand. We could use the batteries of parked electric cars to flatten out the load requirement; let unoccupied spaces get a little warmer or cooler to save on air conditioning and heating loads; use sensors in light fittings to find out where – and when –people go in buildings with uncertain occupancy profiles, such as museums, hospitals or schools. We can understand the flow of people through a supermarket to help us better comprehend behaviour and, in real time, make changes that benefit the customer, as well as the store.

We already have presence detectors at train stations to modulate the volume of announcements – but, if we store and democratise that data, we could let rail companies understand, in real time, how many carriages are required. Taxi companies could predict how much custom they might get from each train – and how late they are going to be. If the connecting bus is already full, more taxis will be needed; this information can help that. The possibilities are endless, limited only by our imaginations; but the point is, without generating data – and, from that data, meaningful information – none of this will be possible.

A lot of the data from building assets will be generated by the building services systems. We design into them all sorts of sensors already and these can provide the data infrastructure that will fuel Digital Built Britain.

Our challenge is to offer not only the building services, but the spine through which data can travel into and out of our projects. This must happen securely, in real time, and in a format that is consumable by the apps that will turn it from noise into meaningful insight. How will we do this? I have no idea, but it sounds cool.

■ Carl Collins is a digital engineering consultant at CIBSE