The Well standard stipulates that 30% of the staff should be able to eat together

For many years, workers have been treated like machines – not people with different subtleties as to what makes them comfortable. Consideration of building users’ health and comfort has been fundamental to the role of services engineers, and now developers are becoming more aware of the importance – not least because healthy buildings could potentially attract higher rents.

The emergence of the Well Building Standard has been one reason for the higher profile of workplace comfort. It is an accreditation system that attempts to measure how building features impact on health and wellbeing. The first European project to receive the Well Building Standard accreditation is the London office of multi-disciplinary engineer Cundall. Being engineers the company was in the perfect position to assess the standard’s scientific credentials.

Compliance requirements for the standard fit into seven key areas: air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, comfort and mind. Each category is scored out of 10 and, depending on the total achieved, silver, gold or platinum certification is awarded.

After attaining the preconditions – 36 out of 102 features for fit-out – the Cundall office at One Carter Lane, opposite St Paul’s Cathedral, aimed for silver certification through additional credits (called optimisations), including monitoring and testing of air and water quality on a quarterly basis. However, after tallying up its provisional scores, gold appears to be within reach. The team – including architect Studio Ben Allen – now awaits formal certification, which Cundall believes will help it to retain and attract staff, as well as make them more productive.

The consultancy is tracking use and absenteeism with a view to identifying whether a healthier environment leads to higher staff productivity. It doesn’t yet have evidence, but others are attempting to make the link.

A web-based energy efficiency company has devised a way of calculating productivity losses as a result of uncomfortable temperatures in offices. Demand Logic’s ‘comfort tracker’ is already monitoring 100 buildings and, according to its creators, offers order of magnitude data about potential problems. The firm also hopes to plot Well Building Standard criteria as more research becomes available.

Material selection

Natural materials are used in Cundall’s 1,400m2 ground-floor office, including solid oak cupboard doors and desk edging, birch ply desks, and a recycled, woven-nylon carpet from a Swedish manufacturer. The plastic floor covering is easy to clean, so Cundall was able to select a lighter shade. As a result, natural light is drawn deeper into the floorplate by bouncing off the reflective material, allowing 30% more daylight into the space.

Alan Fogarty, sustainability partner at Cundall, says: ‘We are now looking at reconfiguring our lighting strategy.

‘We have daylight dimming on the first row of lights, but we’re going to see how many more rows we can dim. It could be as much as 30-40% of the lights on the floorplate, which could be significant in terms of energy reduction.’

Attention to detail makes all the difference. In the kitchen, a brass worktop was chosen for its antimicrobial qualities, while the depth of the sink bowl – and its distance from the tap – were carefully considered to help prevent the spread of germs.

One such test showed that Cundall was almost at three-times the level of VOCs allowed, leaving the team members scratching their heads. It transpired that the building had been cleaned the night before with cleaning fluids that had a high VOC content.

Fogarty says: ‘If the whole operation of the building isn’t considered, it doesn’t matter what you specify in terms of VOCs. You’ll only know what’s happening if you are monitoring and testing the environment.

‘With other rating tools, you produce a piece of paper at the end that says certain materials are low in VOCs. With Well, it doesn’t matter how many pieces of paper you produce – if you fail your test, you fail.’

Air quality

Cundall’s Shanghai office has developed a monitor that measures all aspects of air quality, including VOCs, formaldehyde, carbon monoxide, NOx, ozone, CO2, temperature and relative humidity. It connects to the internet and sends a reading every 15 seconds.

In high-density areas, such as meeting rooms, Well specifies that a maximum of 800 parts per million of CO2 must be achieved. Cundall’s ventilation system controls CO2 levels by distributing air on a demand basis. So if CO2 levels get high in one room, the system draws in fresh air from another to compensate. Cundall’s green lab is normally the first to lose its air because it has plants to compensate for the deficit. The south-facing meeting room – with a mossy wall – gets natural light, so the plants are even more active and, according to Cundall’s research, are able to reduce ventilation requirements by around 10% (see Cundall’s full study).

Plants are integral to maintaining air quality

The Well Building Standard puts a big emphasis on biophilia – the belief that there is a bond between human beings and other living systems – and Cundall’s research into the restorative effects of plants on human wellbeing has resulted in the installation of a second ‘active’ green wall in the office.

According to Cundall, the richest oxygenation benefits of plants are found in the roots, not the leaves. So the office’s innovative structure is built on a wall that incorporates fans in the plenum, behind the plants, to pull air from the office through the roots, before recirculating it back into the room. Fogarty says: ‘It is fundamental that air is drawn through the root system, where the microbes break down particulate matter.’

Water

Cundall has committed to testing its water quality on a regular basis, including inspections of filters and coils. Because of the high nickel content – and other contaminant – in its water, Well insists on the installation of a filtration system to meet its standards. ‘But because the industrial water filters are not WRAS [Water Regulations Advisory Scheme] approved, Thames Water won’t let us connect them,’ says Fogarty. Equally, Thames Water does not recognise the French standard to which the filter has been tested.

Nabers Indoor Environment tool

The Australian Nabers Indoor Environment (IE) tool measures and benchmarks indoor environment performance of offices.

It offers three rating types – base building, whole building and tenancy – each with a different set of parameters to be assessed.

The tool has a 12-month rating period, and uses quantitative space measurements – as well as results from an occupant satisfaction survey – to assess the quality of comfort conditions. Tested factors are: thermal services, including temperature, humidity and air speed; indoor air quality, including ventilation and levels of pollutants; lighting to maximise daylight and minimise glare and heat; acoustic comfort, including external and internal noise reduction; and office layout, including arrangements of partitions, furniture and equipment in relation to fixed elements such as windows, heating, ventilation and air conditioning.

The team is proposing to get smaller domestic-scale filters, which will be more expensive to run.

Fogarty says: ‘If we are filtering the water to such a high level, what happens when we get home in the evenings and at weekends? It has made some employees question what they are drinking from the tap and whether they should be doing this test at home.’

Lifestyle

Staff consultation resulted in Cundall implementing a strong hierarchy of spaces – including desks, meeting and break-out areas. The Well standard required that there be space for at least 30% of the staff to eat lunch together.

At One Carter Lane, a series of tables and benches have been installed in the foyer, next to the kitchen. This set-up keeps food and work areas separate, and encourages healthy eating.

‘You get people away from their desks so they can switch off and socialise. Part of this is positive peer pressure – people tend to go for healthier food choices when their colleagues can see them eating,’ says Fogarty.

Cundall also provides bowls of fruit for their workers, who walk past intermittently and reach for apples or bananas.

Another Well component is fitness. To comply with its requirements, Cundall funds gym memberships, encourages staff to join running or cycling clubs, and even hosts yoga sessions. ‘We do not force people to exercise – we incentivise them,’ says Fogarty. ‘We have excellent shower and changing facilities so staff that want to work out at lunch, or commute by bike, can freshen up.’

For Cundall, the cost per head to complete Well was £200. While this is a manageable sum for a fit-out, a new-build would have a much bigger price tag.

Fogarty says: ‘The certification fees are calculated per square metre, so it becomes a very big fee for a very big building – even though the activity associated with the Well certification doesn’t expand in the same ratio. I think that’s a mistake, which will deter people from going for certification. But they can get most – if not all – of the benefits of a better working environment by just applying the standard.’

He maintains that Cundall will reap the benefits of its Well certification. ‘Without doubt it will increase productivity – if you give people a better environment, they’re going to be more productive because they are going to enjoy coming to work.

‘That’s a minimum standard – everywhere should be a decent place to work, because you have to earn your living, so you might as well enjoy your workplace.’

Having the Well standard will also help Cundall in the jobs market, Fogarty believes. ‘If we have a certificate to prove that this is healthier than the average office, it should make recruitment easier and help us keep staff for longer. As far as I’m concerned, it’s already paid for itself. There’s such a war going on for staff – firms are looking for anything to give them a differentiator. Also, people are spending a lot more time at work, so the idea that your office is keeping you healthy is a key benefit.’

Fogarty says Well is not about producing a piece of paper, but about delivering a result. Cundall’s score can go up if it implements more features, and – equally – it can go down if the company is not fulfilling its commitments. ‘It constantly encourages you to do more,’ he says.

Project team

Client: Cundall

Architect: Studio Ben Allen

MEP engineer: Cundall

Contractor: QOB Group

Project manager: HUSH

Quantity surveyor: Bigham Anderson Partnership

Comfortably productive

The best way of getting a landlord, developer or property manager to look at staff or tenant wellbeing is to present them with a figure showing how much money they are wasting.

Tom Randall, director and development manager at online data analytics company Demand Logic, says there is a way of measuring loss of productivity.

The firm’s web-based platform – which extracts and analyses data from building management systems – now has an added function called the ‘comfort tracker’. This records space temperature, identifying areas that are too hot or too cold, before calculating productivity loss.

Randall says: ‘People’s productivity can be affected by a whole lot of issues – such as getting out of bed on the wrong side in the morning – which complicates the matter, but it doesn’t detract from the fact that temperature will affect productivity.

‘We’re not saying this number is an absolute, but – used appropriately – it is an indication of the scale of the problem.’

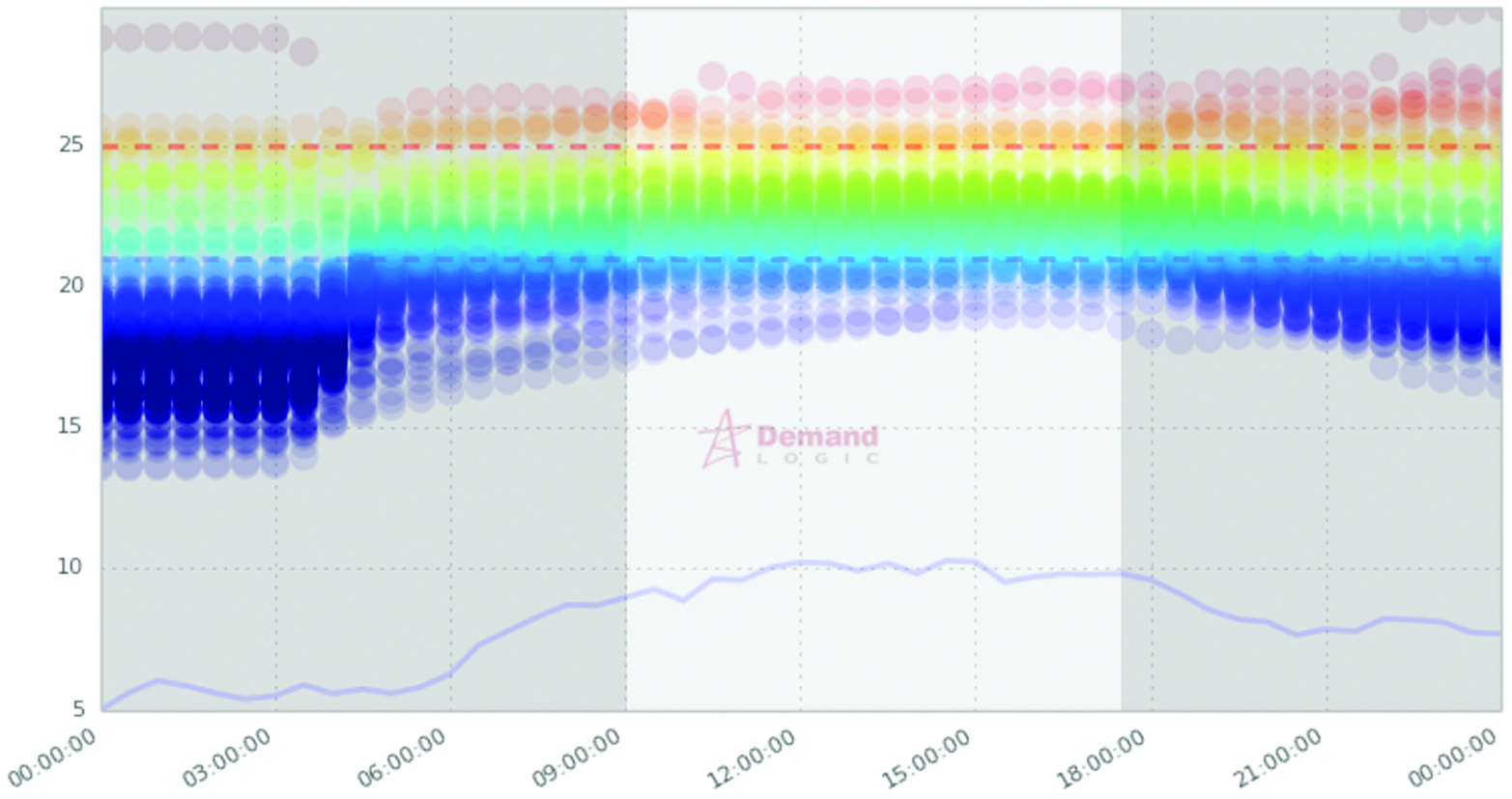

Its method for calculating productivity losses is based on research by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which conducted a ‘meta-study’ of nine studies into how temperature affects productivity. It established the upper and lower temperature thresholds – 21°C and 25°C – within which there is no assumed effect on productivity as a result of temperature.

According to these studies, there is a 2% decrease in productivity when temperatures exceed 25°C, and a 4.7% decrease when temperatures fall below 21°C.

After collecting the sensor data, the algorithm asks to what extent space temperature is outside the productive band of 21-25°C, and for how long. This is then multiplied by the productivity loss percentages, giving the average productivity impact per sensor per occupied period per day.

To work out the monetary annual productivity impact, the platform uses three assumptions, which can be adjusted according to an individual project. In the example below, these assumptions are that:

- There are three people to one sensor

- The average London annual salary is £41,000

- The average combined tax and office overhead is 50%

Multiplying these three assumptions produces the assumed annual staff spend, and this figure is then multiplied by the productivity impact.

Randall says: ‘This gives a reasonable starting assumption that can be adjusted according to more specific data from the client.’

He adds that a single financial figure attracts the attention of landlords or commercial property owners. ‘Asset managers do not want to get bogged down with tables, looking at kilowatt-hours – they want fast, meaningful order of magnitude data. But – as we tell all our clients – this figure must be approached with caution. It is simply a useful indication of issues worth addressing. Comfort tracking provides evidence that can become part of developers’ marketing material and key performance indicators, while paving the way to more targeted condition-based maintenance.’

Future trends

Demand Logic’s platform is currently employed at 60 sites, covering 100 buildings.

One of these is the Financial Times HQ, at 1 Southwark Bridge, London, which has reported that comfort complaints have halved since installation of the platform.

The data analytics company now plans to develop functions to indicate performance against Well Building Standard comfort criteria, including air quality and humidity. But Demand Logic is yet to look at research into the effect on productivity when recommended CO2 or relative humidity (RH) levels are exceeded. ‘But at the very least, we can plot how sensors are performing against the threshold,’ says Randall.

He says further insight can be gained from cross-referencing space temperature data with absence rates, building user survey (BUS) results, and hot and cold complaints. ‘Ultimately, productivity goes hand in hand with comfort. And with the added pressure of tenant satisfaction, retention and landlord reputation, this issue is only going to get bigger.’

Example

Demand Logic applied the ‘comfort tracker’ to a fully occupied, nine-storey, 9,000m², Grade A, 2004 office, in which chillers and boilers serve fan coil units, with four air handling units.

The model assumes that, for each degree above 25°C, productivity decreases by 2%, and for each degree below 21°C, it decreases by 4.7%. By analysing average half-hourly temperatures for each zone (discounting unoccupied times), and using the above model, the calculated total effect on productivity of being outside the thermally comfortable zone is 0.24%. Assuming there are 999 staff members, that the average salary is £41,000, and the average combined tax and office overhead is 50% (factor of 1.5), the approximate annual staff spend is: 999 x £41,000 x 1.5 = £61,438,500

So the estimated total annual loss because of temperature-related discomfort is: 0.0024 x £61,438,500 = £146,000

Thermal profile over time

The dark red and blue circles above or below the dotted lines indicate uncomfortable temperature

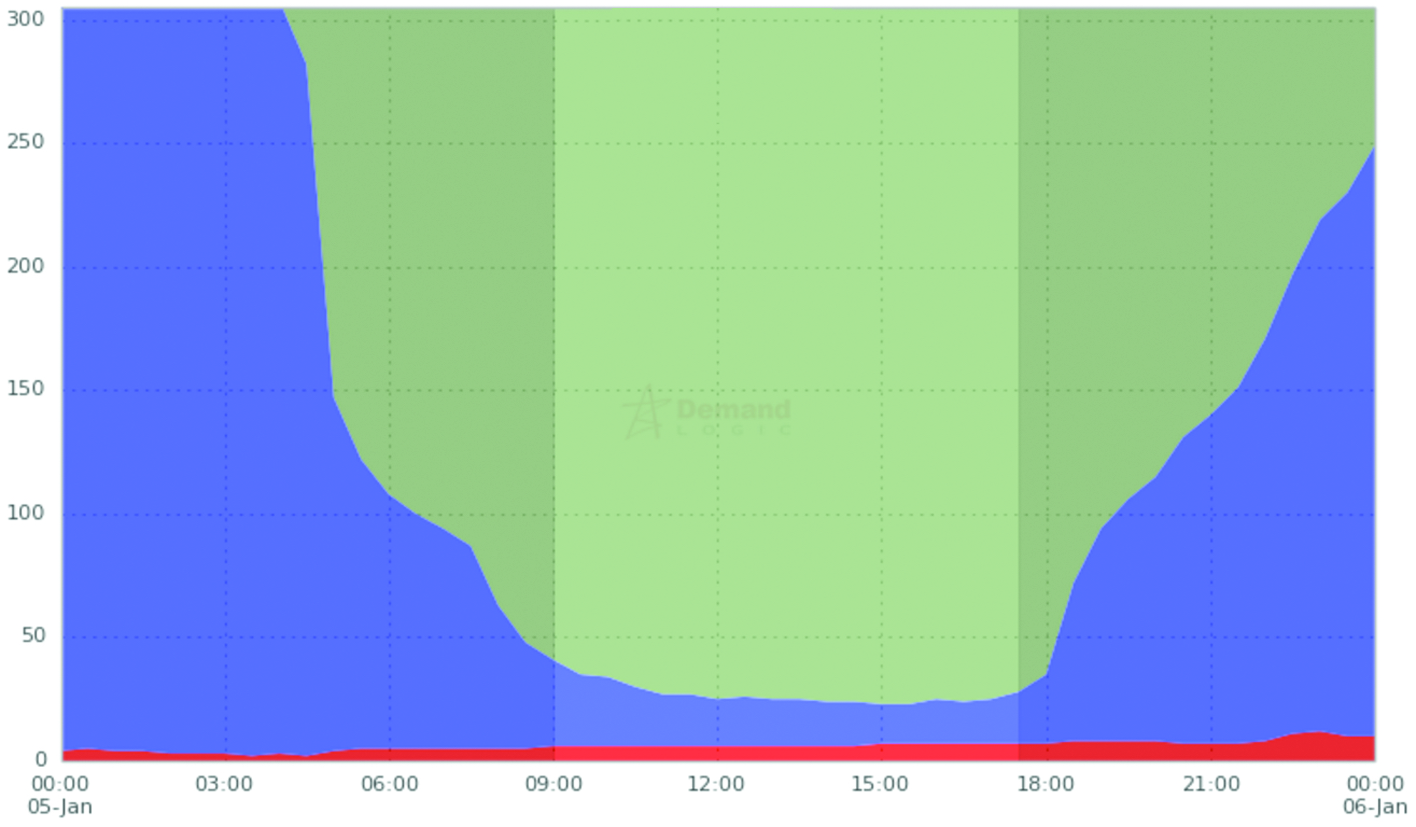

How many spaces were uncomfortable throughout the day?

The red area shows how many spaces were too hot, and the purple shows how many were too cold