With the climate and energy emergencies high on everyone’s agenda and an uncertain winter ahead, our attitude to buildings and their energy usage has altered significantly over the past few years.

We can no longer maintain a business-as-usual attitude to our existing building stock. With potentially crippling energy costs, it is important that these buildings work as efficiently as possible, and that all investments and efficiency recommendations are considered thoroughly and recognised.

The majority of our existing commercial building stock runs poorly. The pandemic showed that empty buildings could not be ‘turned off’, and it highlighted the need to make them more flexible and efficient.

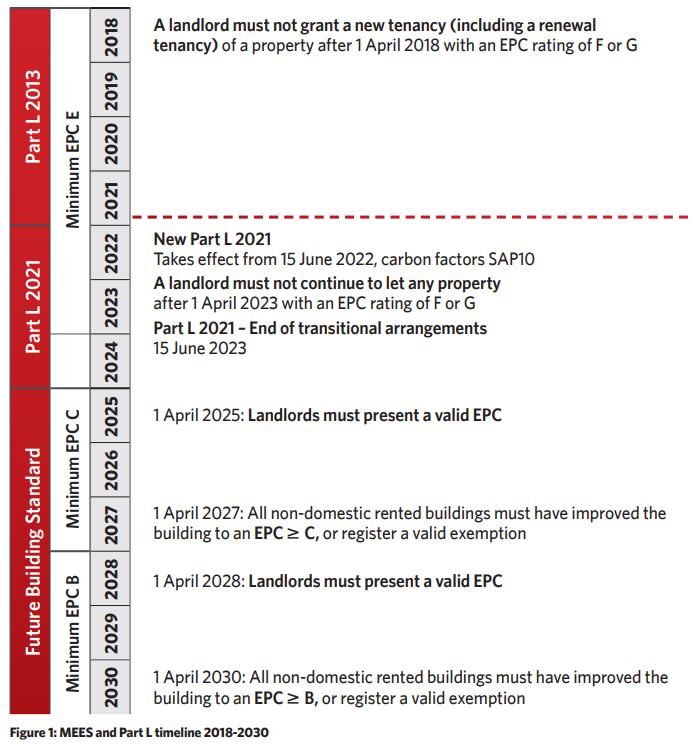

In the UK, there is a legal obligation for commercial buildings to achieve various grades for their energy performance certificates (EPCs) in order to be rented. In the 2020 Energy White Paper, the UK government established the trajectory of the minimum energy efficiency standard of all non-domestic buildings to achieve an EPC B by 2030.

The majority of our commercial building stock runs poorly. The pandemic showed that empty buildings could not be ‘turned off’

This improvement is estimated to apply to 85% of the current non-domestic building stock. A summary of the current EPC requirement trajectory is shown in Figure 1. Should the buildings not reach these targets, they will no longer be able to be tenanted. With large investments readily agreed by building stock owners to meet environmental, social and governance goals it is important that this money is put into the building in the correct places.

To understand this impact on the hotel sector, a study was completed on the effect of energy improvements on the hotel stock for both EPC ratings and actual energy and carbon improvements. This study looked at 120 hotels in a portfolio built since the 1980s.

The National Calculation Methodology (NCM) is used to calculate the EPC rating for building types. It is based on benchmark data and is not supposed to reflect actual operation of the buildings. The NCM has set inputs that cannot be altered, such as domestic hot-water flowrates, occupancy and so on. (See panel, ‘Set NCM inputs’ for the important details for the hotel type that cannot be changed from the NCM.)

Set NCM inputs

- Domestic hot-water flowrate 31.68 L.h-1

- The domestic hot water follows the occupancy schedule; in other words, it is expected that hot water will be used at peak flowrate from 11pm to 7am

- Full load hours daily for domestic hot-water usage = 10.25

- Occupancy = 1 person/20m2 = 0.9 people

- Hot water used per day per room = 292 litres

- The fresh air for the EPC is set at 0.932 l.s-1.m-2; the exterior wall area is 10.76m2

- The total outdoor air entering the bedrooms is 16 l.s-1 person

- The heating setpoint temperature is a steady 20°C, 24 hours a day, year round

When the portfolio of hotels’ actual, metered electricity, gas and domestic hot-water use was assessed and compared against these benchmarks, it showed clearly that the EPC benchmarks were overestimating domestic hot-water usage by 5-10 times their actual usage – which, from the metered data, we worked out to be approximately 30 litres per day on average.

The estimated carbon emissions for the 120 hotels by the EPCs was 32,000 tCO2 a year, whereas for the metered data it showed actual total carbon emissions of 6,000 tCO2. This difference meant that the strategy for reducing actual carbon in the buildings in real life was different from the strategy needed to achieve an EPC rating of a B.

To understand the effect of different energy efficiency measures (EEMs) on the hotels, detailed models were produced in energy modelling software for a set of prototype buildings, broken down by location – city centre or roadside – age and type of HVAC systems installed, to represent the larger building stock.

The study showed that we must find out much more about our buildings before rushing in and installing the latest fad technology

The energy usage of the prototype building models was calibrated with metered data from the actual buildings to validate the energy model. These efficiency measures were then trialled on these calibrated models and the EPC models.

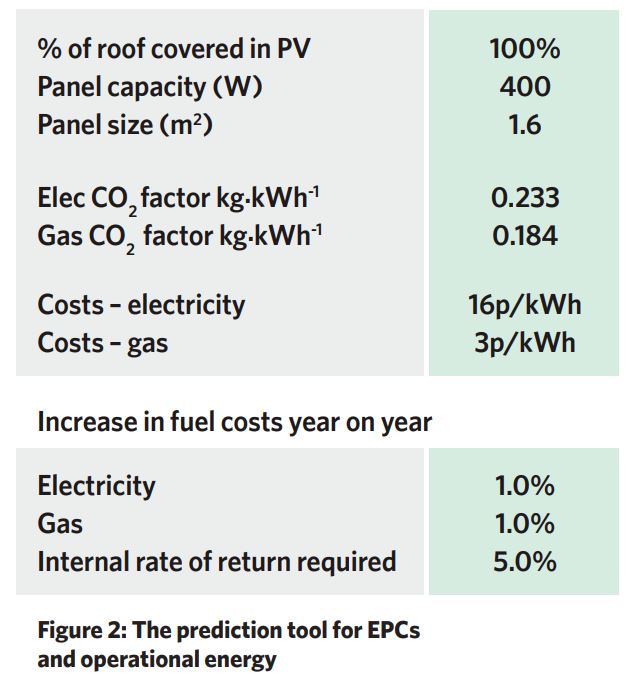

The measures included: installation of LED lighting throughout the building; transferring the domestic hot-water systems from instantaneous electric or gas to heat pumps; improved envelope double glazing; exterior wall insulation and roof insulation; and the installation of PV panels to the hotels’ roofs and car parks. A tool was then created to look at each of the hotels individually and understand what EEMs can be added to the building. Its outputs included the old 2013 EPC prediction, the current (2021) EPC prediction, and the actual operation prediction (see Figure 2).

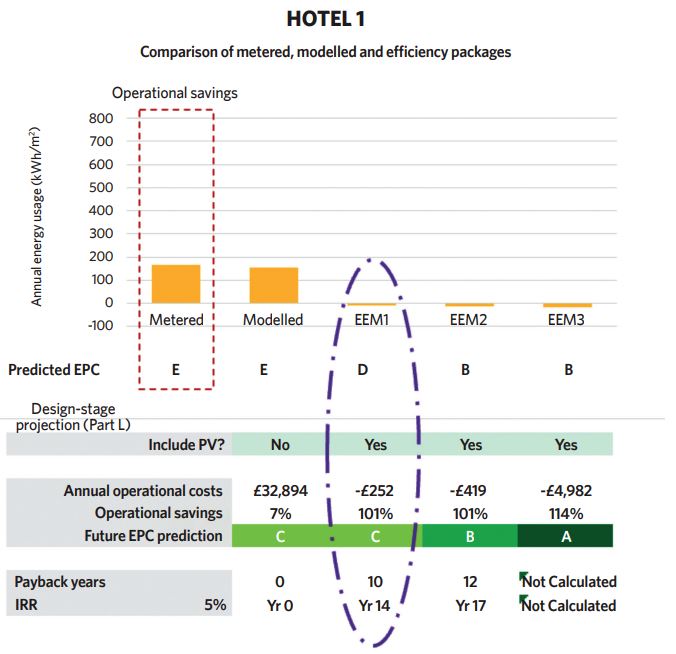

EEM1 is the addition of LED lighting, EEM2 is replacement of the hot water and heating system with a heat pump, and EEM3 represents fabric improvements. There is a button to include PV or exclude it for each option.

The purple dashed line around the EEM1 solution for this hotel shows that the operational energy here is predicted to be negative – this shows a 10 year payback on the LED lighting and PV installation.

The predicted EPC, using current regulations, is a D and using the future carbon factors it is predicted to be a C.

To achieve the required B, a heat pump needs to be installed; however, this is unnecessary as the hotel would already be operating at net zero carbon emissions, so the EPC improves but the payback increases, and the energy savings don’t change. This was the case for multiple hotels and can be seen in the wider analysis paper presented at the CIBSE Technical Symposium 2022.

From this study, it became clear that the database for the NCM needs to be reviewed and updated especially in relation to:

- Domestic hot water for all categories (similar issues have been found for student accommodation and high-density apartment buildings).

- Creating different categories for hotel buildings, as roadside hotels operate and are built very differently from city centre ones.

It is my suggestion that an alternative compliance path should be created for existing buildings. In this case, a building owner can prove their year-on-year savings with actual metered and reported data.

The study also showed that we must find out much more about our buildings before rushing in and installing the latest fad technology. We need to step back and look at the whole building, measure it, analyse it, and improve it from there.

About the author

Dr Annie Marston is chief product officer at REsustain. This work was undertaken with Finlay Milliner, while she worked at Hydrock as technical director leading the building physics team.

For more information

The full paper can be read in the CIBSE Technical Symposium 2022 paper bit.ly/CJOct22AM