When it comes to energy efficiency, we demand more than ever before from our buildings. This does not, however, necessitate the one-size-fits-all approach of sealed spaces with air conditioning. A new generation of buildings can give occupants freedom of control over their environment and a connection to the outdoors. The need to meet stringent energy targets should be an opportunity for engineers to develop novel solutions, specific to each site and tailored to the building users.

An example of these principles in practice is Arup’s recent work on the Simon Sainsbury Centre, part of the University of Cambridge Judge Business School. The 5,506m2 new development will allow the school to operate more efficiently and provide space for its growth.

Arup has been able to offer the client guidance on space flexibility, allowing the building to adapt in the future

The site was located between an existing building and a busy one-way road into the city centre. A shallow plan gave the designers the opportunity to cross-ventilate spaces, but the noisy road meant they could not always rely on occupants to manually open the windows on warm days. The answer was to integrate 60 heat recovery units into the façade to draw fresh air into the building even on the hottest of days. It was the first time this had been done in the UK at this scale.

A concrete structure gave designers the opportunity to use thermal mass to cool the building and, after extensive modelling to minimise solar gain, Arup came up with a services strategy that required minimal air conditioning.

The Cambridge Judge Business School embraced its ambitions to kick-start a site-wide masterplan and create a state-of-the art teaching facility.

An architectural vision to showcase the concrete structure of the building presented an opportunity for storing heat, while lowering energy consumption. A constrained and slender site has become an opportunity to move away from sealed, mechanically ventilated spaces towards a flexible and person-centric solution.

The school was founded more than 25 years ago, as part of the Grade II-listed, John Outram-redesigned Addenbrooke’s building in the historic centre of the city. While the existing buildings formed an important part of the school’s identity and character, they no longer offered sufficient space – or appropriate facilities – for its current and future needs.

A collaborative approach

Arup has a close working relationship with architects Stanton Williams, and was thrilled to be commissioned to enhance, consolidate and expand the school’s facilities on its existing site.

Arup led on the building services design for the Simon Sainsbury Centre, complementing a strong architectural vision for the extension, and ensuring a comfortable environment, minimal energy consumption, and flexibility.

The building is a striking collection of spaces – a testament to an architectural vision conceived and executed with attention to detail. It was completed in October 2017, with students and executive education delegates arriving in January 2018.

3D environmental modelling

Arup’s first priority was to optimise, within the constraints of the site, the building’s glazing, shading and fabric performance. Using a 3D model, it simulated the impact of solar gains on various façade options, and offered guidance on the position of solar panels, the benefit of shading elements, and the differing performance – G-values – of the glazing, depending on the orientation.

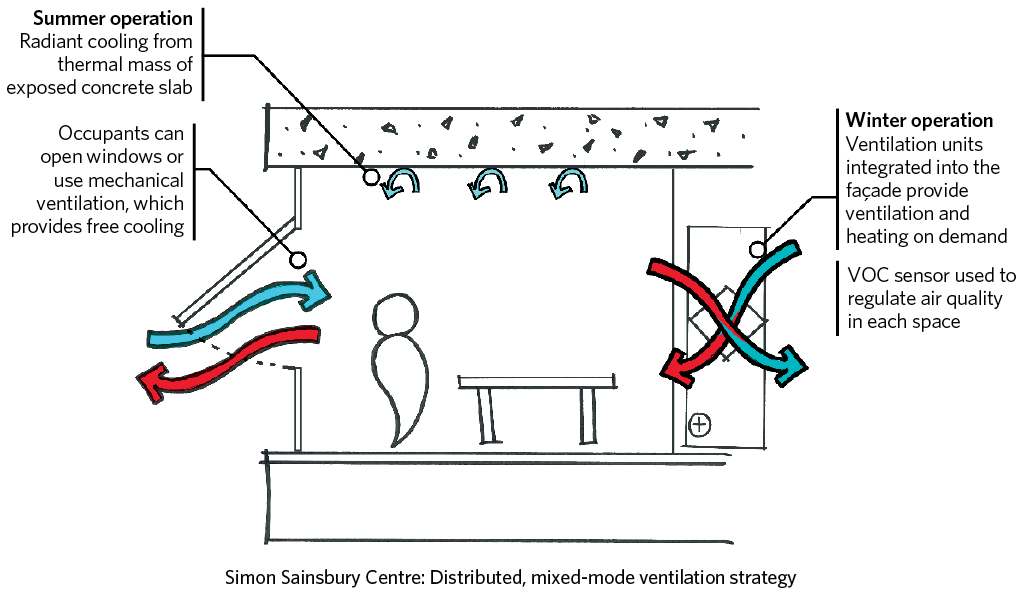

Limiting the solar gains into the offices was the first step in ensuring all spaces operate without the need for active cooling. Arup modelled the building’s performance in various climate-change scenarios against the university’s comfort criteria and the industry standard TM52, to estimate the risk of overheating. The thermal mass of the exposed concrete soffits is used to full effect, together with a night purge. During the warmer summer months, the ventilation system cools the structure during the night. This regulates the temperature throughout the day, reducing the peak temperature experienced by the occupants.

Arup also simulated the effect of partially covering the concrete soffit, and considered using phase change materials to introduce additional thermal mass to reduce the need for air conditioning. However, detailed computer modelling and liaison with a manufacturer determined that the materials available on the market would not regulate the temperature of the building on the hottest of days. 3D modelling at this early stage in the design process and throughout the project allowed for clearer coordination of services.

The dining area has seating for 200 people

Low energy, natural ventilation

The client wanted to avoid active cooling – or air conditioning – wherever possible. With its long-form, shallow floorplan and double-aspect spaces, the site was suited to a natural ventilation strategy. However, it sits adjacent to Tennis Court Road, a one-way street that can become noisy, so relying solely on natural ventilation could have proved disruptive at certain times. The teaching spaces are more intensively used, so these are actively cooled and mechanically ventilated. These spaces are on the ground floor, next to the plantrooms. For the remainder of the building, Arup’s response was to design a mixed-mode building, capable of being ventilated mechanically or naturally. In the summer, users can open the windows. But if it is too cold or noisy, closing the windows automatically enables the room’s heat recovery devices.

The Simon Sainsbury Centre is the first building in the UK to employ the Schoolair low energy ventilation system, designed by Trox Germany, with more than 60 heat recovery units integrated into the façade throughout the building. It uses 10 times less fan energy than a conventional ducted system and, by omitting any high-level ducts, Arup could preserve the clean aesthetic of the building’s exposed concrete soffits. This approach reduces the in-use energy consumption and has allowed the building to exceed the energy requirements of Part L 2013 by more than 25%.

Arup was also the project’s sustainability consultant, and driving down the building’s energy demand was central to achieving a Breeam Excellent rating. The consultancy ensured all office spaces in the building were able to operate without mechanical cooling.

Creating flexible spaces

The building is designed to respond to the changing needs of Judge Business School, which comprises teaching spaces, as well as open-plan and cellular office space. There is also a commercial kitchen and dining area for 200 people. Such multifunctional spaces are an increasing trend; the way in which we use a building can – and should – change over its lifetime.

One advantage of the distributed ventilation system in use at the Simon Sainsbury Centre is that layouts can be changed with relative ease; cellular spaces can be repurposed to create an open-plan office, and the larger floorplates can be subdivided. Arup has been able to offer the client guidance on the opportunities of space flexibility, allowing the building to adapt in the future.

Multifunctional spaces are an increasing trend; the way we use a building should change over its lifetime

By employing an innovative approach to building services, Arup satisfied the multifaceted requirements of this project, despite new challenges emerging in an industry facing stringent regulations.

Its building services design not only preserved the centre’s dramatic and clean aesthetic, but went one step further to exploit the thermal mass of its structure and create an environment that optimises comfort, remains flexible, and uses significantly less energy than a traditional system.

■ Joshua Bird is a senior engineer at Arup