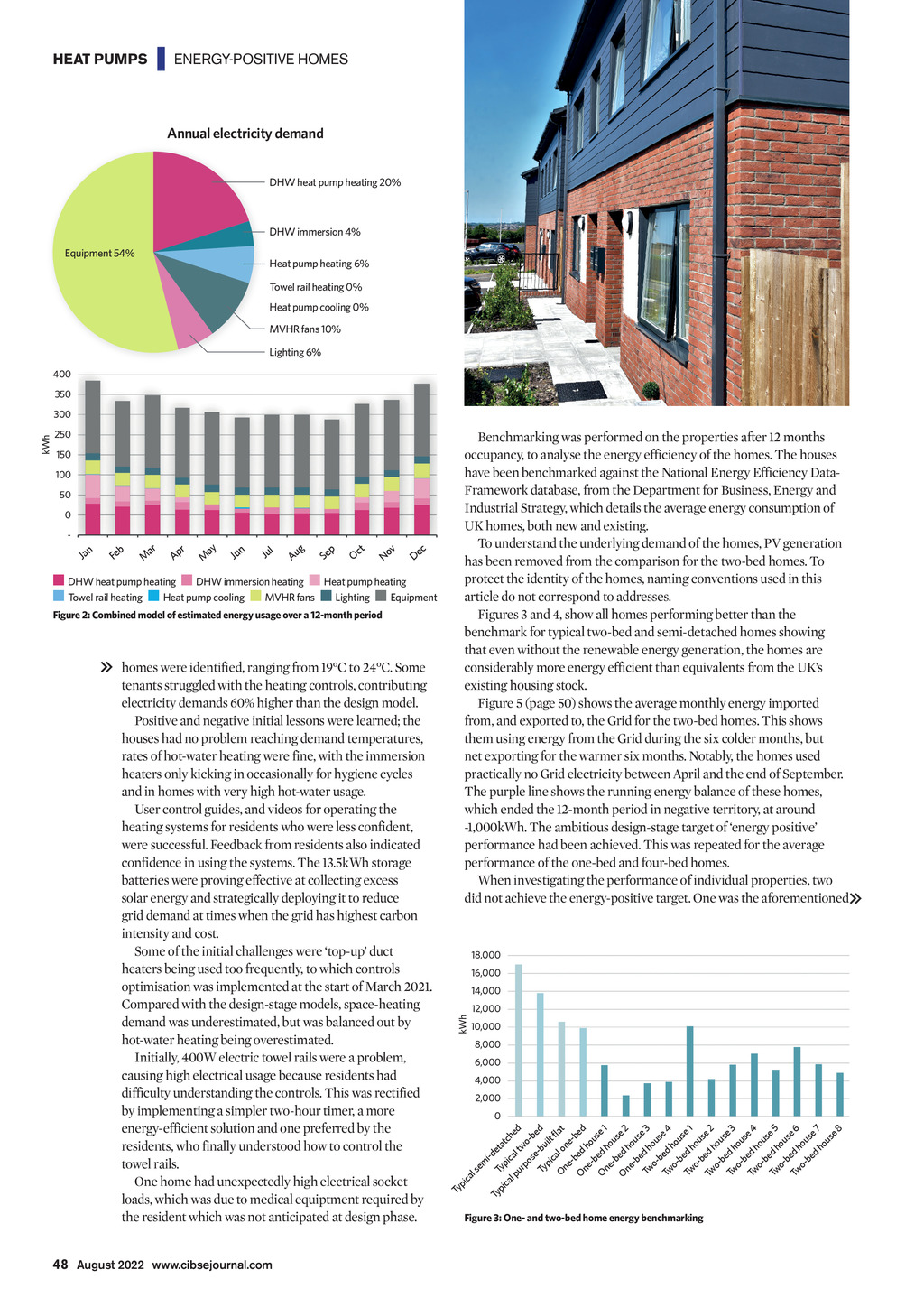

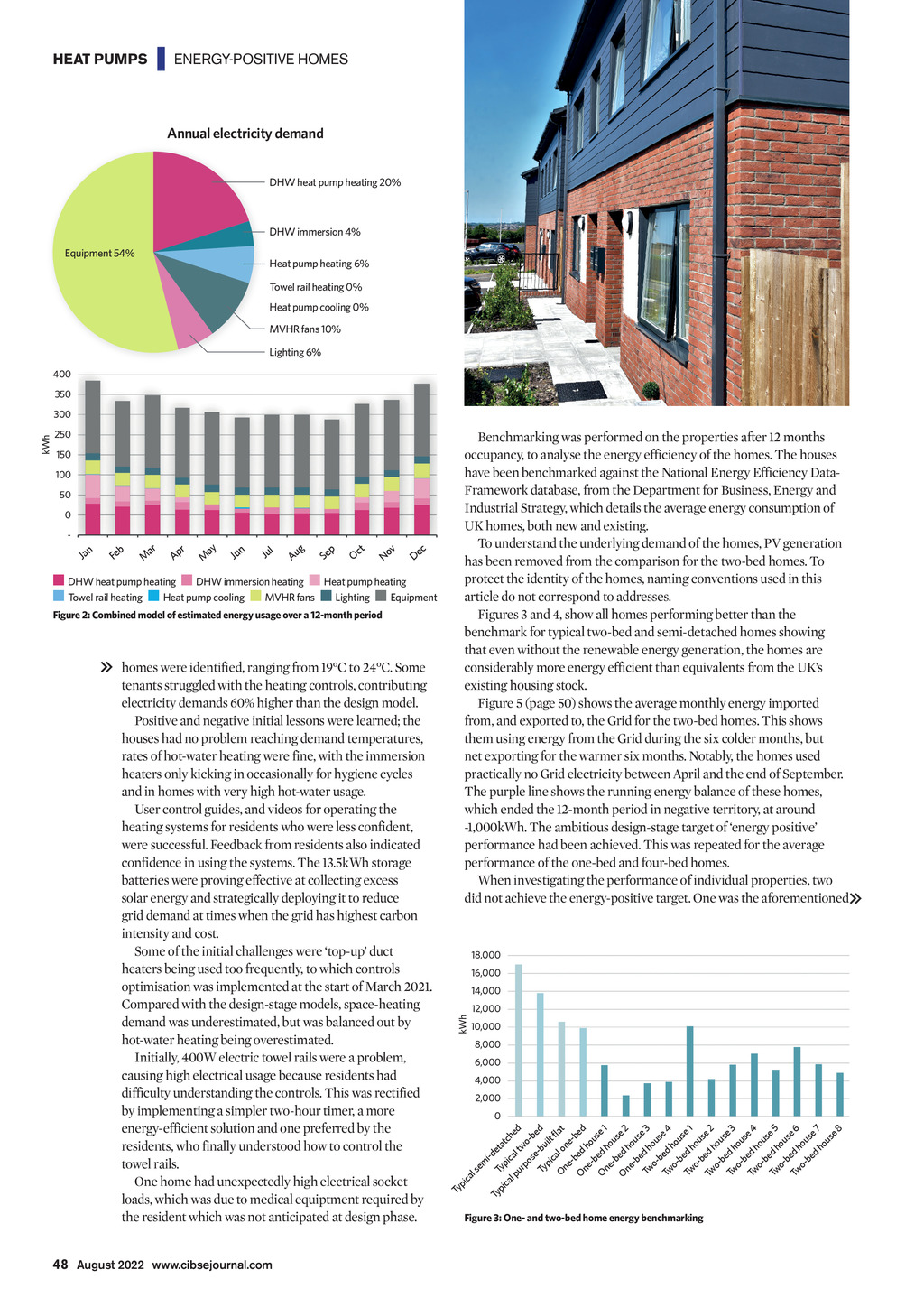

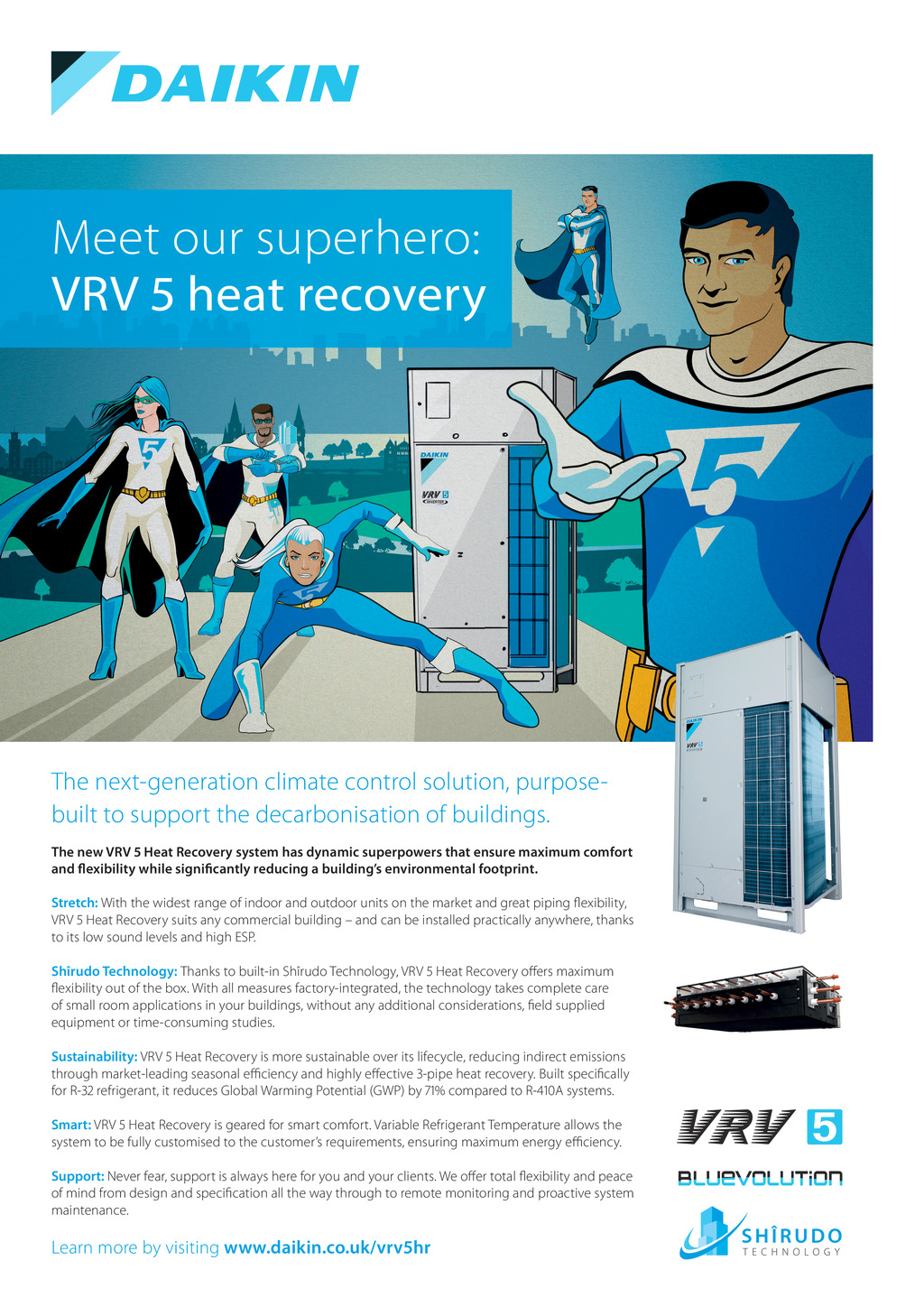

HEAT PUMPS | ENERGY-POSITIVE HOMES Annual electricity demand DHW heat pump heating 20% DHW immersion 4% Equipment 54% Heat pump heating 6% Towel rail heating 0% Heat pump cooling 0% MVHR fans 10% Lighting 6% 400 350 250 150 100 50 0 - n Ja b Fe ar M r Ap ay M n Ju l Ju g Au p Se t Oc v No c De DHW heat pump heating DHW immersion heating Heat pump heating Towel rail heating Heat pump cooling MVHR fans Lighting Equipment Figure 2: Combined model of estimated energy usage over a 12-month period homes were identified, ranging from 19C to 24C. Some tenants struggled with the heating controls, contributing electricity demands 60% higher than the design model. Positive and negative initial lessons were learned; the houses had no problem reaching demand temperatures, rates of hot-water heating were fine, with the immersion heaters only kicking in occasionally for hygiene cycles and in homes with very high hot-water usage. User control guides, and videos for operating the heating systems for residents who were less confident, were successful. Feedback from residents also indicated confidence in using the systems. The 13.5kWh storage batteries were proving effective at collecting excess solar energy and strategically deploying it to reduce grid demand at times when the grid has highest carbon intensity and cost. Some of the initial challenges were top-up duct heaters being used too frequently, to which controls optimisation was implemented at the start of March 2021. Compared with the design-stage models, space-heating demand was underestimated, but was balanced out by hot-water heating being overestimated. Initially, 400W electric towel rails were a problem, causing high electrical usage because residents had difficulty understanding the controls. This was rectified by implementing a simpler two-hour timer, a more energy-efficient solution and one preferred by the residents, who finally understood how to control the towel rails. One home had unexpectedly high electrical socket loads, which was due to medical equiptment required by the resident which was not anticipated at design phase. 48 August 2022 www.cibsejournal.com Benchmarking was performed on the properties after 12 months occupancy, to analyse the energy efficiency of the homes. The houses have been benchmarked against the National Energy Efficiency DataFramework database, from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, which details the average energy consumption of UK homes, both new and existing. To understand the underlying demand of the homes, PV generation has been removed from the comparison for the two-bed homes. To protect the identity of the homes, naming conventions used in this article do not correspond to addresses. Figures 3 and 4, show all homes performing better than the benchmark for typical two-bed and semi-detached homes showing that even without the renewable energy generation, the homes are considerably more energy efficient than equivalents from the UKs existing housing stock. Figure 5 (page 50) shows the average monthly energy imported from, and exported to, the Grid for the two-bed homes. This shows them using energy from the Grid during the six colder months, but net exporting for the warmer six months. Notably, the homes used practically no Grid electricity between April and the end of September. The purple line shows the running energy balance of these homes, which ended the 12-month period in negative territory, at around -1,000kWh. The ambitious design-stage target of energy positive performance had been achieved. This was repeated for the average performance of the one-bed and four-bed homes. When investigating the performance of individual properties, two did not achieve the energy-positive target. One was the aforementioned 18,000 16,000 14,000 12,000 kWh kWh 300 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,000 0 t 1 1 d 3 3 5 7 2 2 d d 6 8 4 4 he -be lt fla -be use use use use use use use use use use use use tc i ta two -bu one d ho ho ho ho d ho ho ho ho ho ho ho ho e l l d d d d d d d d i-d ica ose ica -be be -be bed -be be -be bed -be be be be em Typ urp Typ ne ne- ne ne- wo wo- wo wo- wo wo- wo- woT ls O T T T T T T O T O O p a l c ca pi pi Ty Ty Figure 3: One- and two-bed home energy benchmarking