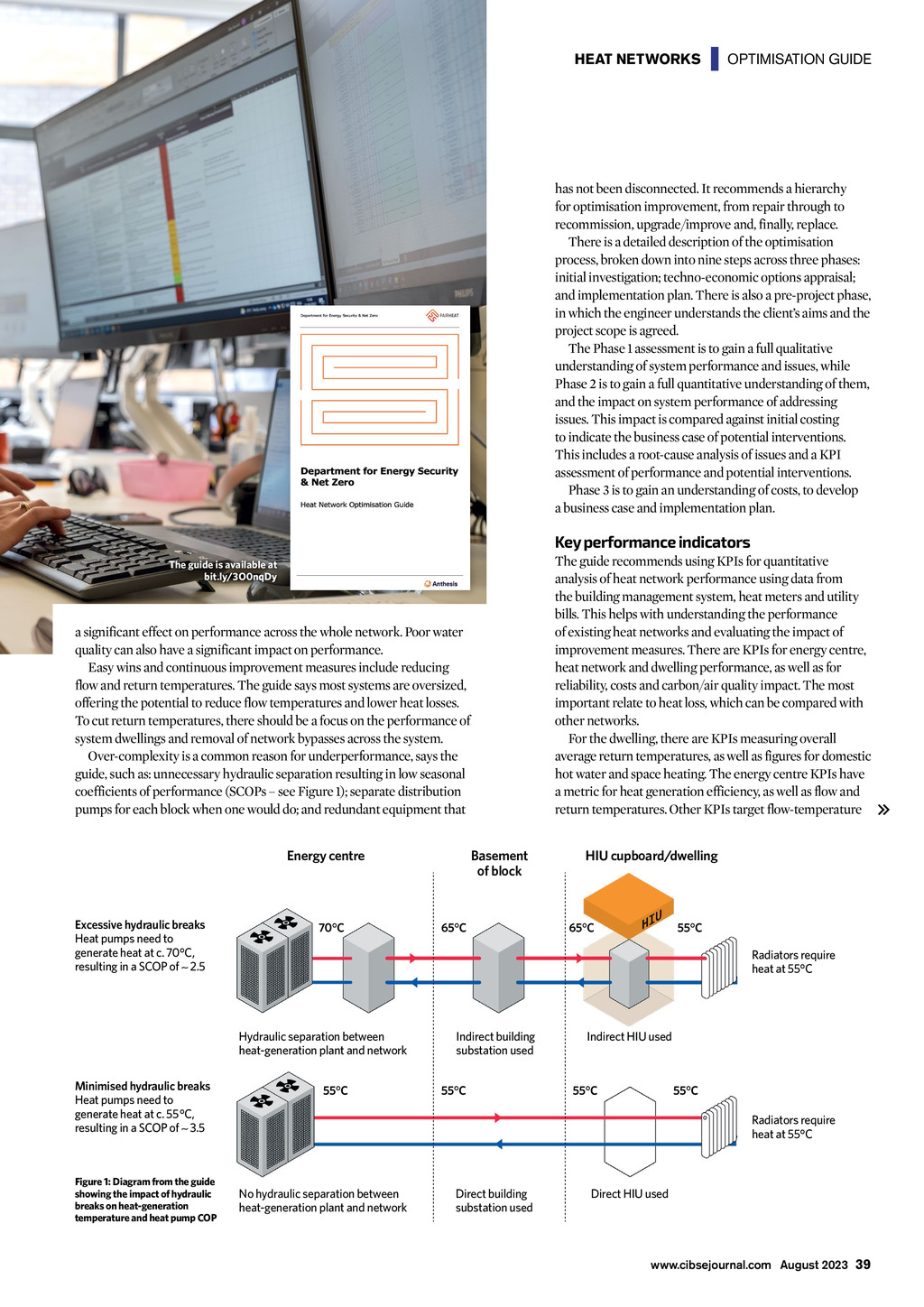

HEAT NETWORKS | OPTIMISATION GUIDE The governments new Heat Network Optimisation Guide aims to improve the performance of existing networks by rigorously analysing performance and making cost-effective interventions that maximise efficiency. Alex Smith reports PHASED APPROACH: OPTIMISING HEAT NETWORKS H eat networks are a key part of the governments strategy to decarbonise heat. While they currently only provide 2% of the heat used in buildings, the Climate Change Committee estimates that around 18% of UK heat could come from heat networks by 2050, to support cost-effective delivery of carbon targets. There are around 14,000 heat networks in the UK, but government-funded analysis over the past eight years has revealed a myriad of issues affecting performance that risk undermining the governments goal of providing affordable, low carbon heat. To address the situation, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero last month published a Heat Network Optimisation Guide. Targeted at consultants and specialists, it aims to standardise the performance of existing residential and mixed-use heat networks but the principles apply to all heat networks. The main purpose of this guide is to provide a standardised set of processes and approaches that anyone who is undertaking optimisation can use, with the aim of providing a standard minimum quality, says co-author and FairHeat lead engineer Tom Burton. The guide complements the Heat Networks Technical Assurance Scheme (HNTAS) guidance, which together with the CIBSE Heat Networks Code of Practice will legally oblige heat network operators to adhere to minimum technical standards from 2025. Its objective is to identify the root of suboptimal performance and outline business cases for improvements (see panel, 16 common reasons for failure). Burton urges the industry to get behind the guide: The more engineers and specialists there are providing operators with the information they need to improve customer experience and efficiency, then the closer we will 38 August 2023 www.cibsejournal.com be to providing low carbon, affordable heat to residents, and a reliable level of service. The guide is based on heat network investigations by FairHeat in two government programmes: Heat Network Optimisation Opportunities and the Heat Network Efficiency Scheme Demonstrator. Key performance indicators (KPIs) based on this analysis capture the underlying performance and resilience metrics of heat networks, and feature in the optimisation guide. They feed into both the cost and carbon intensity of heat, says Burton. Four-phase approach The guide recommends taking a four-stage phased approach: understand; stabilise; easy wins; and continuous improvement. Once root causes have been understood, the stabilisation of a heat network should take place to improve performance and reliability, it says. Easy wins can then be carried out that have short payback times but require more planning and design. The continuous improvement cycle is designed to enhance performance over a long period. It has four repeating stages measure, analyse, test, and implement. Consumer heating systems have the biggest impact on performance, followed by district/communal distribution systems and energy centres, says the guide. End users are at the top of the optimisation hierarchy because their requirements dictate the minimum flow temperature at which the network can operate. Minimising flow and return system temperatures results in the lowest possible heat losses across the entire heat network. As the minimum flow and return temperatures are largely set by dwelling equipment, they are the most important element to optimise, states the guide, which describes typical measures to stabilise the network, and lays out easy wins and continual improvements. Of key importance is stopping uncontrolled network flowrates, which can result in high pump energy consumption and higher heat losses. The three main actions to get network flow under control are: removal of network bypasses; elimination of end user bypasses; and control and/or replacement of pumps. Often, a small proportion of dwellings are responsible for most of the flow on the network, which means it only takes a few bypassing units to have