In the event of a fire, the largest contributor to deaths and injuries is smoke – not the fire itself. More than 60% of deaths occur as a result of being overcome by gas or smoke and, similarly, inhalation of smoke causes around 60% of injuries.

Controlling smoke plays a large part in reducing these statistics, as well as protecting the building. People specify and install smoke control systems both to protect escape routes and to assist fire fighters. Legislation, such as BS 9999 and 9991, focus on these objectives.

Smoke control systems can also protect stock and machinery, as well as reducing the risk of roof collapse. These aspects are not legislated for, but many building owners and occupiers will nevertheless specify smoke control for these reasons.

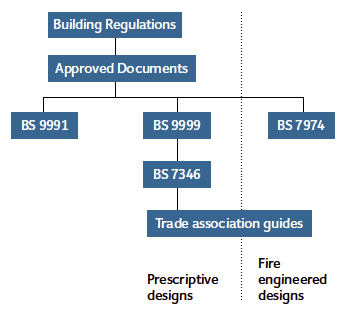

In the UK, smoke control systems are subject to an ever-evolving, complex network of standards and legislation. The standards represent a hierarchy (see Figure 1), with the most important documents at the top.

The process of updating these documents means there are some inconsistencies between them; it takes time for an update in one document to filter through to another that covers the same theme or one related to it.

Figure 1: Standards hierarchy

No recent changes have been made to legislation in England and Wales. The latest change was the repeal of fire protection provisions in the Local Acts in 2013. This rationalised the requirements across England and Wales, but reduced the level of fire protection in large buildings, where provisions previously existed.

On the horizon – but not before 2017 – is the next revision of Approved Document B (ADB), since the existing one is now 10 years old and showing its age.

In residential buildings, BS 9991: 2015 Fire safety in the design, management and use of residential buildings code of practice is a welcome update to the 2011 edition and is supported by the Smoke Control Association (SCA) document referred to below.

The contentious recommendation for pressurisation of escape stairs in all buildings with a floor higher than 30m has been replaced with a recommendation for either mechanical shaft ventilation or more sensible pressurisation. Mechanical shaft ventilation is less costly and less complicated than pressurisation, and could be the only option if travel distances are to be extended. It adds guidance for mechanical shaft ventilation, either as a direct alternative to a natural shaft, or for extended dead-end travel distances. This is useful because ADB is too outdated to include mechanical shaft ventilation.

For natural – and mechanical – shaft systems, the standard builds on the guidance in ADB, including a recommendation to:

- Limit shaft leakage to 3.8 m3·h-1·m-2 at 50 Pa

- Exclude non-shaft-related services, such as pipework or cabling from the smoke shaft, which could otherwise cause system failure

- Locate the shaft remote from the stair, enabling the whole corridor to be ventilated.

The new BS 7346-8: 2013 Components for smoke control systems. Code of practice for planning, design, installation, commissioning and maintenance offers both technical and procedural guidance, including useful pro-forma for certificates for all stages. It is referred to in BS 9991.

The second edition of BS 9999 DPC: Fire safety in the design, management and use of buildings code of practice has been issued as a draft for public comment, and is likely to be published in 2017. It covers all buildings apart from residential, which are dealt with in BS 9991 (as described above). The update will bring consistency with BS 9991 and regularise good practice that had been poorly defined.

It mirrors BS 9991 in recommending mechanical shaft ventilation or pressurisation of fire-fighting cores in buildings with a floor higher than 30m, and adds guidance on mechanical shaft systems. For natural shaft systems, this standard builds on the guidance in BRE report 79204: Smoke shafts protecting fire-fighting shafts: their performance and design, relating to shafts for fire-fighting stairs, including recommendations for:

- Shaft ventilators

- Excluding non-fire related services from smoke shafts, as with BS 9991

- Locating shaft terminations in negative pressure areas.

Last October, the SCA published a revision to its guidance on Smoke Control to Common Escape Routes in Apartment Buildings (Flats and Maisonettes), which is available free at www.feta.co.uk/smokecontrol It is a reference point for those involved with the design and approval process of such systems, bringing together all the relevant details and giving recommendations not previously covered.

This revision expands on BS 9991:2015, and offers helpful design information, including design fire sizes, tenability criteria and suggested timelines for the design process. It also gives guidance on the standard of ventilation and controls equipment to be used, along with guidance on installation, commissioning and maintenance.

The Runcorn site of the Ineos ChlorVinyls waste-to-energy plant, where Colt designed and installed labyrinth natural ventilators, adhered to ISO9001: 2008

The guidance is particularly helpful when extended travel distances are proposed. It contains the first piece of published guidance recommending a maximum dead-end travel distance in an extended corridor protected by a suitable mechanical shaft ventilation system of 30m – as measured from the stair, not from a protected lobby door.

It has useful diagrams showing how to measure the free area of a ventilator for several common practical applications – extending the guidance of Diagram C7 in ADB – and gives illustrative design tenability conditions for firefighters.

It also reflects changes in architectural practice. For example, there is often a limitation of the space available at the top of the staircase in many small single-stair apartment buildings. This can make it difficult to incorporate a natural ventilator – which had previously been proscribed – so a mechanical solution is often adopted to save space. This guidance sets out helpful performance criteria for designing such a system.

It provides useful guidance on the layout and ventilation of exit routes from the stairs at the final exit level, the purpose of which is to avoid smoke logging in this area.

Although going through final stages of preparation, the EU EcoDesign Energy Efficiency Regulation for fans raises some issues. But in its drive for efficiency, there is concern that dual-purpose systems – commonly used in car parks – could be adversely affected. The high temperature smoke extract fans and jet fans cannot meet the efficiency requirements that have been initially proposed. This could significantly affect installed cost and space requirements, and might make the systems less efficient.

Harmonised standards for EN12101

European standard EN 12101 Smoke and heat control systems covers products and systems in the field of smoke control. Its first part – of a planned 13 – was published in 2003. Currently, six parts have been published as harmonised standards:

- EN 12101-1: Specification for smoke barriers

- EN 12101-2: Specification for natural smoke and heat exhaust ventilators

- EN 12101-3: Specification for powered smoke and heat exhaust ventilators

- EN 12101-7: Smoke duct sections

- EN 12101-8: Smoke control dampers

- EN 12101-10: Power supplies.

- EN 12101-6: Specification for pressure differential system. Kits is also harmonised but, as written, it is impossible to test to this standard so a new edition is being produced.

Part nine, covering control equipment, is the only harmonised part of EN 12101 that is not yet published. The other parts of the 12101 series cover design and installation and will not be harmonised. It is not clear whether any of these will be implemented in the UK, although the existing ones have not been.

Since 2013, the Construction Products Regulations (CPR) have required all products covered by a harmonised standard under the Regulations to be CE marked.

For smoke control products, independent testing and certification to the relevant part of EN 12101 are required, leading to manufacturer application of the CE mark. While this was already a requirement across most of Europe, it did not previously apply in the UK (see panel, left).

These standards are being gradually revised, with the aim of improving the standard of testing. A helpful change to EN 12101-3 – which now permits testing with variable speed drives (inverters) and includes jet fans – was published in 2015.