Students at Parrs Wood High

Parrs Wood High is a thriving, state-maintained comprehensive school in Manchester, with an extraordinary story to tell. Over the past eight years, successive members of the student sustainability team have worked tirelessly to cut annual carbon emissions by 543tC02e, resulting in annual savings of £106,000 and an improvement of two Display Energy Certificate (DEC) bands for each of the three main buildings.

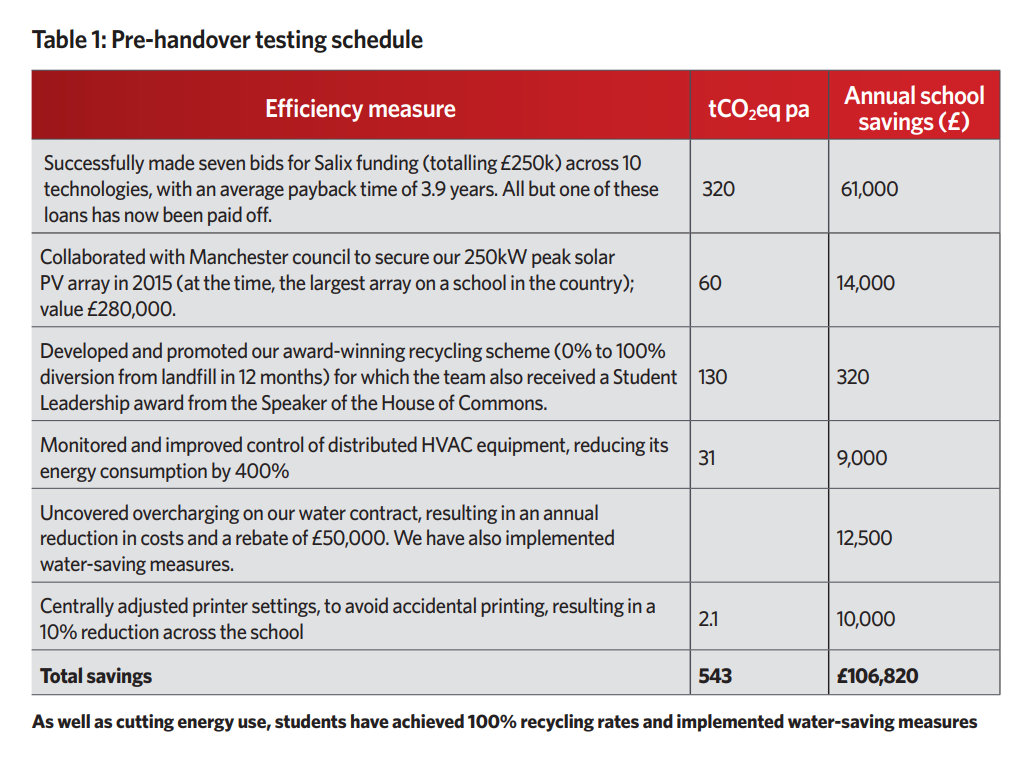

In that time, they have identified areas for improvement, calculated payback periods, selected contractors, secured funding, and project-managed the majority of the work. As well as cutting energy use, the students have achieved 100% recycling rates and introduced water-saving measures (their key achievements are shown in Table 1).

Recently, students completed a full appraisal and costing for an LED lighting upgrade in preparation for a Salix funding bid later this year. They are currently working to eradicate single-use plastic bottles in school, with a potential reduction of 100,000 bottles per year.

The school is used by Salix Finance and the Department for Education (DfE) as a national role model, and the students have given advice to the DfE, finance officers, site managers and students from other schools.

Parrs Wood High has a mix of buildings, ranging in origin from the 18th to the 20th centuries, as well as a small amount of new build. The majority of schools in the UK have a similar mix of building stock. Work to upgrade and retrofit equipment at the school has been achieved with limited funding and limited technical knowledge at the outset.

How Parrs Wood delivered

The huge reductions in carbon have been achieved by a group of sixth-form students – the CO2 team – who meet at least twice a week and employ the help of younger students. They draw on the knowledge gained in lessons and through their relationships with staff.

One of Parrs Wood’s strengths is its extremely diverse mix of students, and this is reflected in the CO2 team; its members’ broad range of backgrounds and interests means they approach tasks from a variety of perspectives.

Why pay for a carbon-literacy course when universities and businesses are keen to help for free, as part of their outreach programmes, and contractors are keen to give free surveys and quotes

Each year, the CO2 team tackles at least one large sustainability issue. For each issue, they apply 10 key principles. Projects must be applied to real-world problems and the model must be simple. The projects must be costed and quantified, and monitored afterwards to ensure any issues are rectified. Implementation has to be simple and we consider how real-life behaviour will affect the likelihood of success.

Students have access to financial accounts so they can see the consequences of their actions. We never pay for advice – outside organisations are willing to share knowledge and carry out surveys for free. (See panel, ‘Ten steps to success’).

How it started

The work was started in response to student demand. As young people become increasingly aware of the need to protect the environment, they not only want their schools to be more sustainable, but also want to be involved in making this happen.

The work gives students the opportunity to apply the knowledge and skills learned in their academic studies to the real world, and develops their ability to quantify issues to make informed decisions. Importantly, it makes them appreciate that, in the real world, with limited resources, finding solutions is often not clear-cut and involves difficult decisions between competing priorities.

As we have seen recently, protesting can be a valuable way of raising public awareness around environmental issues. However, it does not begin to find solutions to the problems. To make a real difference, large numbers of people need to be engaged in making achievable and permanent changes. Schools, and in particular their students, are ideally positioned to spread this practice beyond school, to their homes and future work environments. Ultimately, it’s about encouraging people to take responsibility for solving their problems, and not rely on someone else to do it for them.

Next steps

Having become experienced in tackling a range of sustainability issues, the school is now keen to share this knowledge.

As well as publishing articles, the students have been briefing relevant organisations on their work and how it can be better supported. The team is currently working with Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) to develop a package to encourage student leaders and staff in other schools.

A lack of time, technical knowledge and confidence that students and staff can tackle more complex issues involving technological solutions were all identified as barriers by other schools.

The CO2 team will be producing online resources this year, which will give clear technical guidance for other schools. It will have activities for students, and include links to the curriculum, as well as financial advice to enable them to access Salix and other funding. Above all, we want to convince students and teachers in other schools that they can initiate significant change, and that it’s not something that has to be left entirely to ‘experts’.

Finally, one thing other schools should definitely be made aware of is just how addictive this work is. While people often complain about getting out-of-hours emails, I get them from a diverse and motivated team of students telling me about their latest research and possible solutions to problems – which, for me, makes this the best job going.

10 Tips to Success

The following underlying principles have helped make each year’s team highly effective:

- The work is applied to real school issues, to develop the ability to find solutions that are viable and rooted in the real world.

- A simple model is used: identify issues/opportunities; assess the scale of the issue and potential savings/cost; shortlist alternative solutions; brief school management; secure funding; implement change; assess the impact.

- Quantify, so you are able to make informed decisions. While not all members of the team will be studying mathematical-based subjects, the group as a whole should be quantifying issues and developing this skill.

- Assess impacts: our experience shows that measures don’t always work as expected and initial snags need to be ironed out. A failure to monitor impact can result in unintended increases in energy consumption.

- Clear milestones: at the end of each of the above steps, a student presentation/report is produced. This gives a clear time-limited target and forms the starting point for the next stage.

- Keep it simple: while the initial assessment and solution may be complex, the implementation must be straightforward in operation or it will fail to deliver desired results. The best way to encourage a desired behaviour is to make it the easiest option1.

- Be realistic about behaviour change and what it can achieve: in large, busy shared spaces, a sign reading ‘please turn off the lights’ will have little impact, and a technological solution may be required.

- Openness: students should have access to relevant accounts to assess the financial impacts of measures.

- The site team is an invaluable source of information and our greatest ally for implementing effective change.

- We don’t pay for advice: why pay for a carbon-literacy course when universities, businesses and other experts are keen to help for free as part of their outreach programmes

About the author

Chris Baker is a science teacher and coordinator of the student C02 sustainability team. For further information, please contact c.baker@parrswood.manchester.sch.uk

The school is extremely grateful to Salix, the local authority, and other organisations for their willingness to engage with its students.

References

1 Behaviour change and energy use, The Behavioural Insights Team. (2011). London: Cabinet Office. bit.ly/CJApr20CS1