The updated methodology for calculating energy use in new residential developments is set to have a significant impact on the way consultants design heating systems for the purpose of Building Regulations compliance.

One of the biggest changes in the draft Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP 10), published in July, is to the lower carbon emissions factors for electricity, which reflects the rapid decarbonisation of the National Grid.

Other key updates include higher distribution loss factors in heat networks, and measures taken to reduce risks of overheating (see panel ‘Important changes in SAP 10’).

It is not known when SAP 10 will come into effect. The new methodology will only supersede SAP 2012 when the Building regulation conservation of fuel and power: Approved Document L, is next updated, which will be in 2019 or 2020.

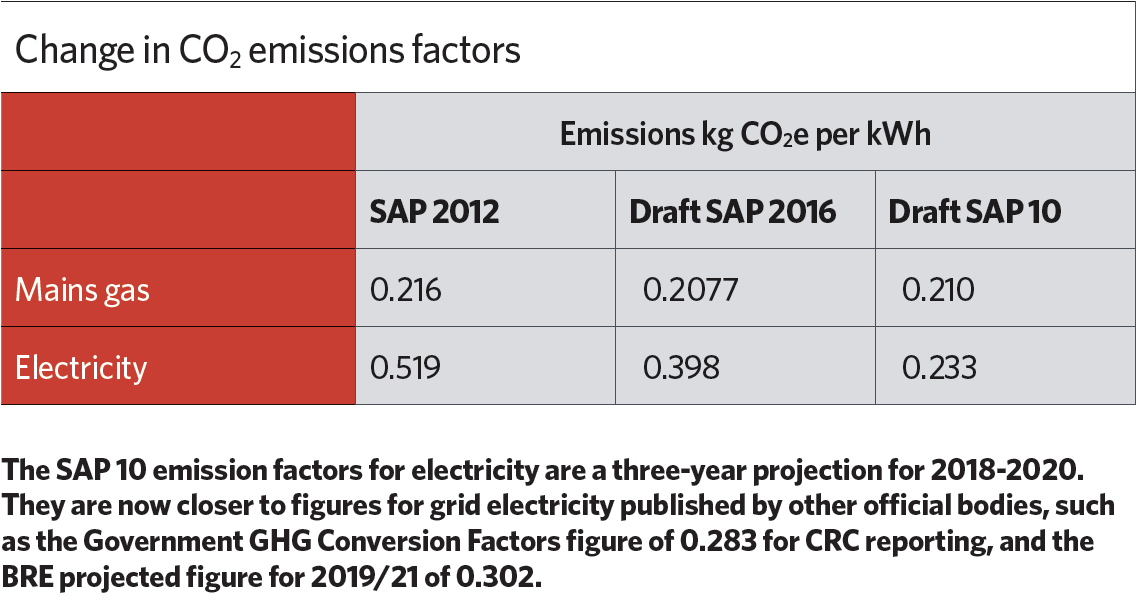

Many of the SAP changes were outlined in BEIS’ Proposed Changes to Government’s SAP (November 2016) and its response to the consultation a year later, but figures for CO2 emissions factors in SAP 10 are far lower for electricity than in 2016.

What is SAP?

The purpose of SAP is to assess the energy and environmental performance of new homes to ensure developments meet energy and environmental policy initiatives, as well as building regulations.

The assessment is based on standardised assumptions for occupancy and behaviour. This enables a like-for-like comparison of dwelling performance. Related factors, such as fuel costs and emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), can be determined from the assessment. These indicators of performance are based on estimates of annual energy consumption for the provision of space-heating, domestic hot water, lighting and ventilation.

SAP is used to assess energy use and carbon emissions for Building Regulation Approved Document L in domestic buildings, while SBEM is the equivalent tool for non-domestic buildings. Reduced data SAP (RdSAP) is used to produce Energy Performance Certificates.

Current SAP assumes that electricity used produces 2.4 times the carbon emissions of mains gas. The 55% reduction in the CO2 emissions factor for electricity means homes heated by direct electric systems will produce virtually the same CO2 emissions as gas, while heat pumps will produce even less. The SAP 10 factor is also far lower than the carbon factor proposed in 2016 (see table ‘Change in CO2 emissions factors’).

‘SAP 10 has aligned the carbon factors with reality,’ says Julie Godefroy, acting head of sustainability development at CIBSE. ‘The new carbon factors and distribution losses will change the appraisal of low carbon heating options.’

Phil Jones, past chair of the CIBSE CHP-DH group, carries out feasibility projects for CHP schemes. ‘CHP is still the most economic, but it is increasingly falling down on CO2 emissions, particularly where lower carbon factors for electricity are already being used.’ This is the case in schemes supported by the Heat Networks Delivery Unit, set up to administer government grants for heat networks, says Jones.

The lower carbon factors mean heat pumps only need a coefficient of performance (COP) of 1.1 to have carbon emissions lower than a gas boiler, says Elementa senior engineer Clara Bagenal George, MCIBSE.

However, she warns of an unintended consequence of a lower carbon factor – higher energy bills. ‘Electricity is more expensive than gas, so to be running cost neutral, the COP of a heat pump would need to be four. Hence, further guidance will need to be introduced to protect a building’s occupants from increased energy bills.’

The shift in carbon factors will change how design teams prioritise carbon reduction measures, she says, because the relative cost/carbon tonnes of different measures has changed. For instance, CO2 emissions from grid electricity falling by 55% means the relative cost per carbon tonne of PVs increases substantially.

‘It is still important to install PV on buildings to help to continue reducing the carbon emissions of the UK grid,’ she says. ‘Further incentives or metrics may be needed to ensure this.’

Jones says the lower carbon factors are overdue, and should be used now in making SAP calculations. ‘I’m very concerned about carbon factors in the SAP proposals. I welcome the much lower electricity grid factor of 0.233, but we are close to this already. Why do we need to wait until 2020? Are we still going to be assessing heat pumps at 0.519 then?’

This view is supported by Bean Beanland, vice-chair of the Ground Source Heat Pump Association. ‘If the carbon factor in SAP and Part L is not changed soon, we will be faced with buildings still going up in 2022 that have been designed on false principles. Significant damage is being done to the heat pump sector every day that this situation is allowed to perpetuate.’

Hanaé Chauvaud de Rochefort, senior policy research manager at the Association for Decentralised Energy, says: ‘The changes to the grid electricity emission factor are appropriate. However, it is problematic for all power generation as the grid emissions are a blend of all sources of generation on the system.’

‘Gas CHP – even at very low grid emission factors – continues to displace higher emission generation, such as gas engines and turbines without heat recovery.’

Remeha CHP’s general manager, Mike Hefford, says carbon factors change depending on the season. ‘The concern is that the current approach is based on an overly simplified annual average intensity figure for grid electricity. This approach is flawed when dealing with heating as it fails to take into account the fact that the grid is cleaner in summer than winter,’ he says.

Consequently, technology using electricity supplies for heating will appear significantly lower carbon than its real-world operation, says Hefford. ‘We would therefore urge the government to adopt a more accurate monthly average intensity figure for grid electricity.’

Important changes in SAP 10

- CO2 emission factors, primary energy factors and fuel prices, have been updated

- Default distribution loss factors associated with heat networks have been increased

- The assumed heating pattern has been changed to a consistent daily pattern for all days of the week

- The assessment of summer internal temperatures has been refined

- Additional design flow (heat emitter) temperature options have been provided for heat pumps and condensing boilers, which affect their efficiencies

- Default heat pump efficiencies have been updated

- The calculation of lighting energy has been updated to allow recognition of new lighting types with higher efficacy

- The options for entering heat losses from thermal bridges have been revised

- The calculation of hot water consumption has been adjusted to account for shower flow rate

- Battery storage is now accounted for in calculations for PV panels

- The impact of PV diverters is now taken into account

- The overshading factor used for the PV calculation can be taken from Microgeneration Certification Scheme data

The BEIS 2017 consultation response said it would assess the technical feasibility and impact of changing the carbon emission factor calculation to a monthly method.

(It stressed that this did not mean the target for new buildings would vary month to month.)

It also said gas emission factors would be updated again at the time of the Building Regulations change, when regulatory impact would be assessed.

SAP 10 assumes higher heat losses from heat networks than SAP 2012, unless the performance data has been entered into a product characteristics database (PCDB), where a distribution loss factor is calculated and recorded for use in SAP.

If heat networks are not in the PCDB, the distribution loss factors (DLF) are 1.5, if they are designed to the CIBSE Heat Networks: Code of Practice for the UK (CP1). If the code is not followed, a DLF of two must be used. In other words, SAP 10 assumes that half of the heat generated by the system is lost in the network.

There are lower DLFs for new buildings connecting into existing heat networks. These range from 1.2 for pre-1900 dwellings to 1.5 for those installed in 2007.

Jones welcomes the fact that compliance with CP1 gives a better DLF in SAP proposals, but asks how a designer proves compliance and who has the competence to sign this off.

Jones says CP1 will be updated in the autumn to include more checklists against key outputs, so each stage can be signed off by the client and its technical advisers. He says the approach to DLF in SAP 10 should also be used in SBEM – the calculation for energy use in non-domestic buildings.

Overheating

SAP 10 has been changed to tackle the causes of overheating in homes. It has reduced the amount of ventilation designers can assume is being gained from opening windows. ‘SAP 2012 was too optimistic about how much heat gain could be removed from ventilation. Even assuming the windows are open, the removal of heat gain has been halved,’ says Godefroy.

‘The changes make a big difference. As you will get as much benefit from ventilation gains, designers will have to reduce heat gains in other areas, such as less glazing,’ says Godefroy.

She is pleased that SAP software will also prompt designers with questions about the suitability of using opening windows, such as: is there a local source of noise likely to prevent windows from being left open for a long period; and is there a security risk if windows are left open unattended?

The BRE has invited anyone with comments on the draft document to email SAP-help@bre.co.uk