Only 9% of UK engineers are women. This alarming shortfall is something that International Women in Engineering Day (Inwed), on 23 June, aims to tackle, by drawing attention to the amazing careers in engineering available to women, and by celebrating the achievements of outstanding female engineers.

Building services consultancy ChapmanBDSP is one of the sponsors of this year’s Inwed, organised by the Women’s Engineering Society (WES). The firm recognises it has some way to go to achieve a 50:50 male/female split in its workforce and graduate intake. However, it has a plan of action, including going into schools as a science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) ambassador, offering more work placements to female students, and being involved with WES.

‘As part of Inwed, we will be inviting former work experience people and interns to our offices to meet our engineers and look at some demonstrations and presentations taken from our current projects,’ says Kathryn Cox, HR director at ChapmanBDSP. ‘Staff will also be able to bring a female school/college-level relative to work on that day, to participate.’

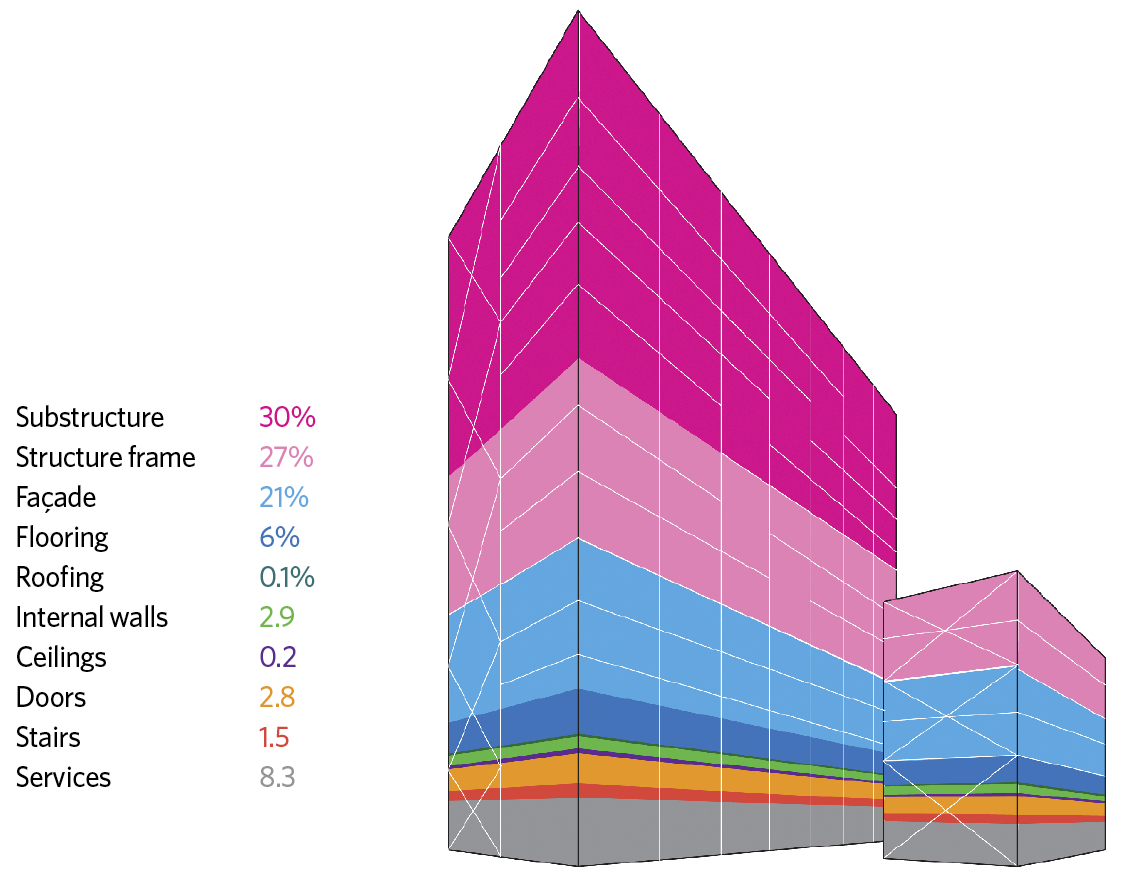

Embodied carbon as per building elements (%)

One project that will be profiled is the £120m Centre Buildings Redevelopment (CBR) for the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), which ChapmanBDSP has worked on with architect Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. This involves the demolition of four existing buildings on LSE’s Aldwych campus, to be replaced with a state-of-the-art, flexible and highly sustainable academic and teaching building. (See panel, ‘LSE’s centre point’.)

What’s interesting about this building is that there has been an unusually high proportion of women on the design team. To find out how this has affected collaboration, problem-solving and the often adversarial attitudes found on construction projects, we talked to three members of the team.

Lucy Vereenooghe, director at ChapmanBDSP

Lucy Vereenooghe

Lucy Vereenooghe heads up the ChapmanBDSP team responsible for MEP, environmental and lighting design at LSE CBR. A director at the firm, she switched to services consultancy after studying civil engineering at the University of Leeds.

‘Like many, I sort of fell into it,’ says Vereenooghe. ‘I was good at maths and physics at school, and my maths tutor suggested I consider engineering. Yes, it was male-dominated – more so than now – but I didn’t see that as an obstacle.’

‘I’m lucky that I got that push from my teacher, because I hadn’t thought about engineering at all and had no perception of it,’ says Lucy. ‘Once I looked into it, and saw how vocational it was, it appealed to me. I did consider mechanical engineering, but I’ve always been interested in architecture and the built environment, so that led me to civil engineering.’

Vereenooghe has always worked in building services and didn’t find the switch from civil engineering an obstacle. ‘I think as long as you are numerate, keen and willing to learn, that’s the main thing – there’s a lot more to it than just your exams and studies.’

As part of its diversity policy, ChapmanBDSP aims to increase the number of women in the firm through events, such as Inwed, and the wider support of WES. The firm’s workforce is 21% female, with 13% of fee earners being women. ‘A lot can be achieved through better role models for young women – and that includes getting more women on the board. Work also needs to be more flexible in terms of hours and part-time working, and the stigma around taking paternity leave needs to be removed, so men can share in the childcare.’

Vereenooghe describes the fact that so many women were involved in the design of CBR as nothing less than ‘extraordinary’ – and it had positive benefits. ‘There was a good team dynamic and women are quick to forge good relationships, which I think pushed people to try even harder. It was less adversarial, with discussions between the team smooth and open, and less formal. It’s certainly one of the most enjoyable projects I’ve worked on.’

Tamsin Tweddell, senior partner, Max Fordham

Tamsin Tweddell

Max Fordham is client adviser on soft landings and sustainability at CBR, led by senior partner Tamsin Tweddell. ‘The strong female representation was refreshing. The client reps were female and the tone of the working environment comes from them; it was collaborative right from the start,’ she says. ‘There was the space to throw in ideas, without them being dismissed, ridiculed or quashed; there was an ability to disagree with someone respectfully. There were strong-minded individuals, but discussions were less adversarial than usual, and very positive.’

Relationships were forged in an interesting teambuilding exercise – creating a model of the proposed CBR out of gingerbread. ‘This got the project and relationships off to a great start,’ says Tweddell.

Tweddell is currently the only female senior partner at Max Fordham and, last year, was elected as a one-year director. ‘Two such posts exist each year, in addition to our longer-serving directors, which is an excellent way to give people exposure to this role and to understand how the business is run in more detail.’

Of the firm’s 177 engineers, 24% are female – the proportion having increased steadily from 17% in 2012 – and the figure rises to 34% at graduate-engineer level. Engineering did not feature as a career option for Tweddell, either at school or after gaining a physics degree at the University of Cambridge. However, a spell at Sunseed – a practical centre for low-impact living and environmental education in southern Spain – ignited a passion for the possibilities in sustainability and low-energy building design. ‘It showed me the positive impact that engineering can have, and that sustainability went beyond animals, plants and conservation.’

Tweddell was crowned Woman of the Year at the 2016 Building Awards and believes getting female role models into schools to talk about engineering is the way forward.

Federica Ariu, associate director, AKTII

Federica Ariu

A passion for drawing led Federica Ariu to structural engineering, and has taken her from a small practice in Milan to renowned London-based firm AKTII. ‘I’ve always wished to move to this city, because of the high-profile projects here and the opportunity to work with leading architects.’

Ariu describes the LSE project as ‘quite unusual. I could really appreciate some differences. On this project women were able to easily find common ground and a way of problem solving. I think we all felt comfortable in a short time. It was a good experience.’

AKTII is active within Women in Science and Engineering (WiSE) and is seeking to increase the number of female engineers in the firm. Its initiatives include women engineers going into schools to explain the work being done on landmark projects such as the CBR. ‘Firms do need to address issues such as flexible working, and increase opportunities for male partners to help with the family.’ There are 52 female staff in AKTII – around 22% of the workforce.

‘My message to young women considering a career in engineering is this: if you really like something, then go for it. Don’t be put off by it being male-dominated.’

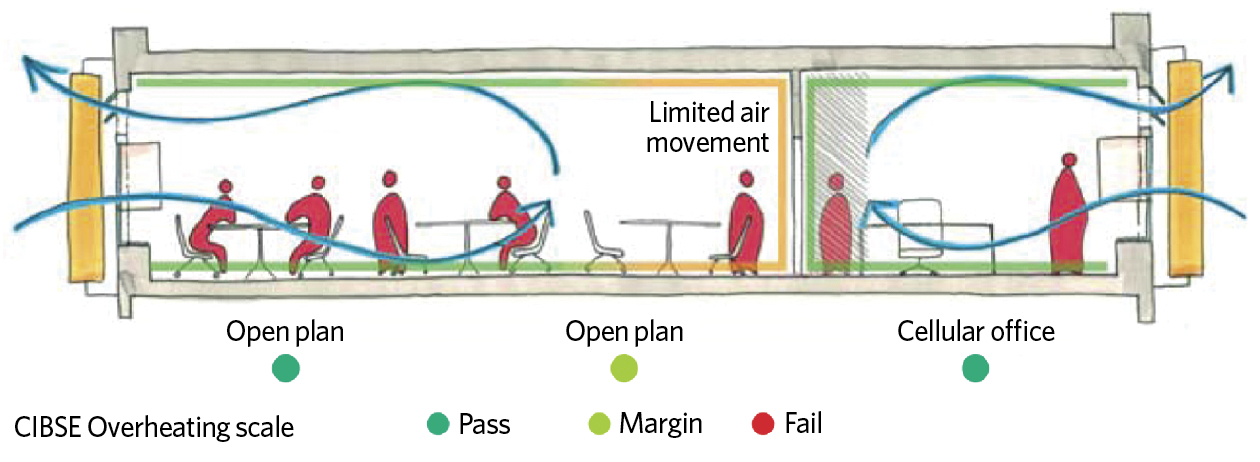

Section showing spatial arrangement (open plan or cellular) and effect of natural ventilation

LSE's centre point

The LSE’s CBR will replace four Aldwych campus properties: East Building, Clare Market, the Anchorage and the eastern part of St Clement’s. These were no longer fit for purpose and the decision was made to demolish the buildings to make way for a new, efficient development, with more space.

The new building will increase the gross internal floor area of the centre buildings from 12,000m2 to nearly 15,508m2, allowing for growth in the school. In addition, there will be a new landscaped public square at the north end of Houghton Street.

One of the main objectives of the LSE’s estates strategy is for the quality of the buildings to be commensurate with its international academic reputation.

The CBR will be a statement, landmark building and boast strong environmental credentials. It aspires to be a highly carbon-efficient building, achieving Breeam Excellent in design to create a better environment for its occupants. The services strategy aims to minimise demand for energy, while opting for an efficient, low-carbon supply that includes biofuel combined heat and power (CHP) and solar photovoltaic (PV).

The new building will accommodate teaching and learning spaces of various sizes on the lower-ground, ground, first and second floors, a teaching and learning commons on the ground floor, and academic departments on floors three to 12.

‘A simple and robust design combines the best elements of passive design with innovative and inventive MEP plant and controls, making it easy for users to adapt their individual environment on academic floors,’ explains Lucy Vereenooghe, director at ChapmanBDSP.

The result is a predominantly naturally ventilated building. ‘The success of the natural ventilation strategies to ensure comfort will rely on factors such as understanding of the controls, occupant interaction with controls, acceptance of noise levels from outside, fresh-air quality, achieving acceptable levels of air movement, and avoiding excessive air movement,’ adds Vereenooghe.

Interiors have exposed thermal mass in the ceiling to stabilise diurnal temperature variations through night-time flushing of heat absorbed during the day. It is proposed that the top windows be triple glazed and supply daylight into deeper areas. They are openable and motorised, allowing for exhaust of hot air from spaces, and are controlled by the building management system (BMS) to enable overheating control and night-time ventilation for heat purge from the thermal mass.

Demolition of existing buildings started in June 2015 and was completed in December 2016. The new building is expected to be finished by summer 2019. Handover will be followed by a two-year soft landings period, led by Max Fordham.

Project details

Client: London School of Economics

Architect: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

MEP, environmental and lighting consultant: ChapmanBDSP

Soft landings and sustainability: Max Fordham

Structural engineer: AKTII

Project manager: Deloitte

Main contractor: Mace