CIBSE’s 2022 Building Performance Champion, the Library and Study Centre at St John’s College, Oxford University

Last year, following a review of past award submissions, CIBSE introduced new data entry forms for its 2022 awards. The aim was to offer more clarity for applicants on the essential information needed, and to provide a clearer and fairer basis on which judges could assess the entries.

The changes were also intended to make the awards of more value to the industry, as the building performance data can more easily contribute to the CIBSE energy database (if the entrants agree).

We have reviewed this year’s awards to identify any improvements that could be made to the entry forms. We wanted to assess the quality of the data and identify any trends in building performance among the entries.

Quality of data

Last year’s changes introduced a quantitative data entry form, alongside the usual more qualitative and descriptive form. The data was grouped in three categories: essential; recommended, but not essential; and optional.

‘Essential’ is basic information on the project, approach to in-use evaluation and disclosure, and the simplest level of information about the building’s energy use and supply systems. For projects only connected to the gas and electricity grids, this tab was enough to obtain the total energy use, but not if onsite systems were present.

‘Recommended, but not essential’ is the contribution from onsite energy generation systems. In the review, this section was filled in by all entrants.

‘Optional’ is information such as air permeability, the project delivery process – for example, whether Soft Landings was followed, or energy performance modelling carried out – breakdown into energy uses, and peak demand. All entrants completed at least some of this section, with many filling in the majority.

The review of 2022 entries shows that the large majority went far beyond providing only the essential information.

The new forms have also removed a lot of the ambiguity in past submissions – for example, whether the declared energy use included that from onsite systems; what type of floor-area measurement was being used; and the time period covered by the data and whether it represented normal occupancy. All of these could lead to significant uncertainty when trying to get a picture of data quality and the building’s performance.

The quality of data received from the majority of entries is encouraging, particularly given the effect of the pandemic on access to data and resources available. For this year’s awards, the following changes will, therefore, be introduced.

There will be only two categories of data entries – ‘essential’ and ‘optional’. Most of the information previously ‘recommended’ will become ‘essential’. This covers onsite energy systems, so that ‘all projects will now have to submit enough data to assess the project’s total energy use, including grid as well as onsite supplies’.

Air permeability is also to become an ‘essential’ entry; this recognises its importance as a key building performance parameter, and the fact that a test is carried out on new buildings and some retrofits anyway.

As previously, the new forms will allow entrants to respond ‘not sure’ or ‘not available’, where necessary.

What the data says about building performance

Last year, one of the aims of the data review was to identify best-performing projects and where they sat against RIBA 2030 Challenge and LETI One-pager targets for offices, schools and homes. The data from this year will feed into similar analysis for further sectors, as part of the ‘bottom up’ approach to developing targets that are not only compatible with the UK’s net zero carbon budgets, but also achievable.

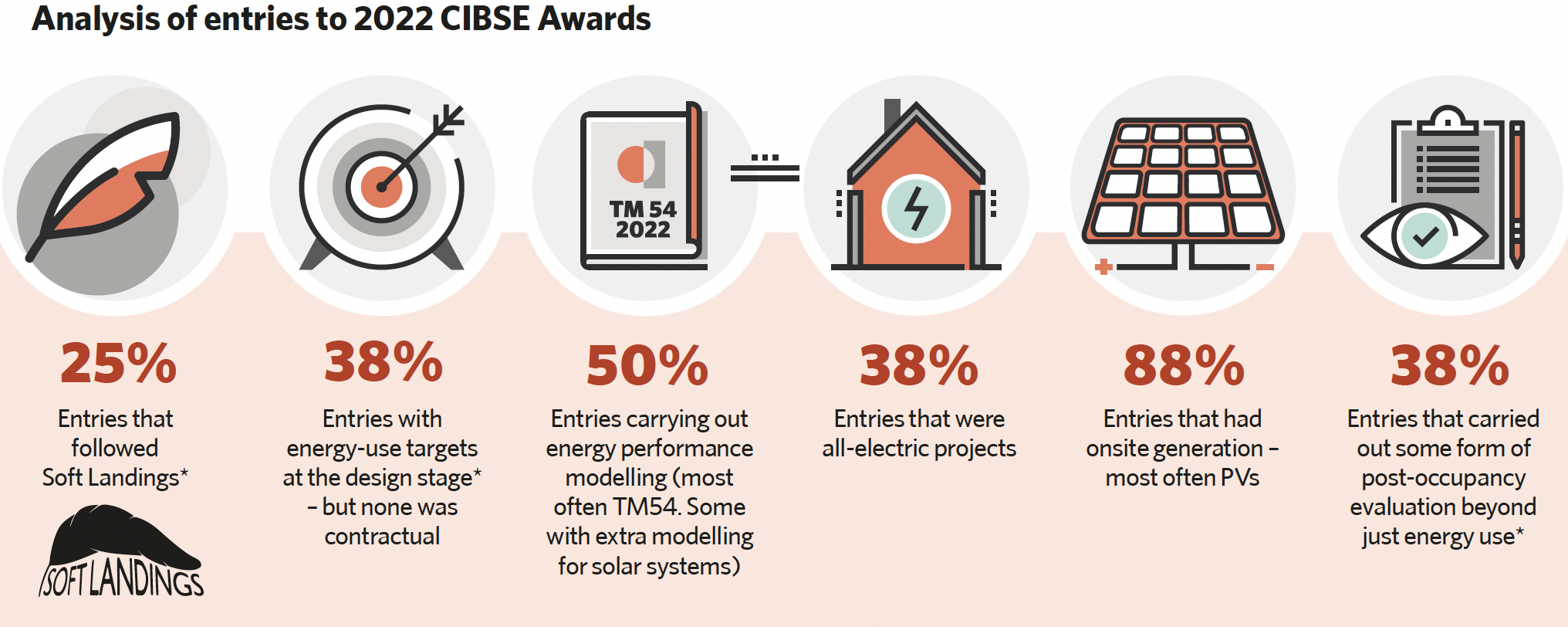

This year’s data shows trends in delivery processes and design solutions, illustrated below. As expected, projects paid attention (probably more than average) to setting energy targets beyond regulatory compliance at the design stage, following Soft Landings, and carrying out energy performance modelling. The large majority of projects have some sort of onsite generation systems.

The Library and Study Centre at St John’s College, Oxford University was this year’s overall Building Performance Champion, and epitomises these trends. The scheme followed Soft Landings, and TM54 modelling was carried out to inform energy-use targets and to aid the assessment of in-use performance.

* Sometimes, the information was not provided in the submissions. For example, it is possible that more projects had energy-use targets at the design stage, but that the entrant did not fill in this question on the entry form

Currently in its third year of occupation, the project is still subject to fine-tuning and analysis of its energy performance, including monthly, end-use breakdown, and key systems, such as the heat pump.

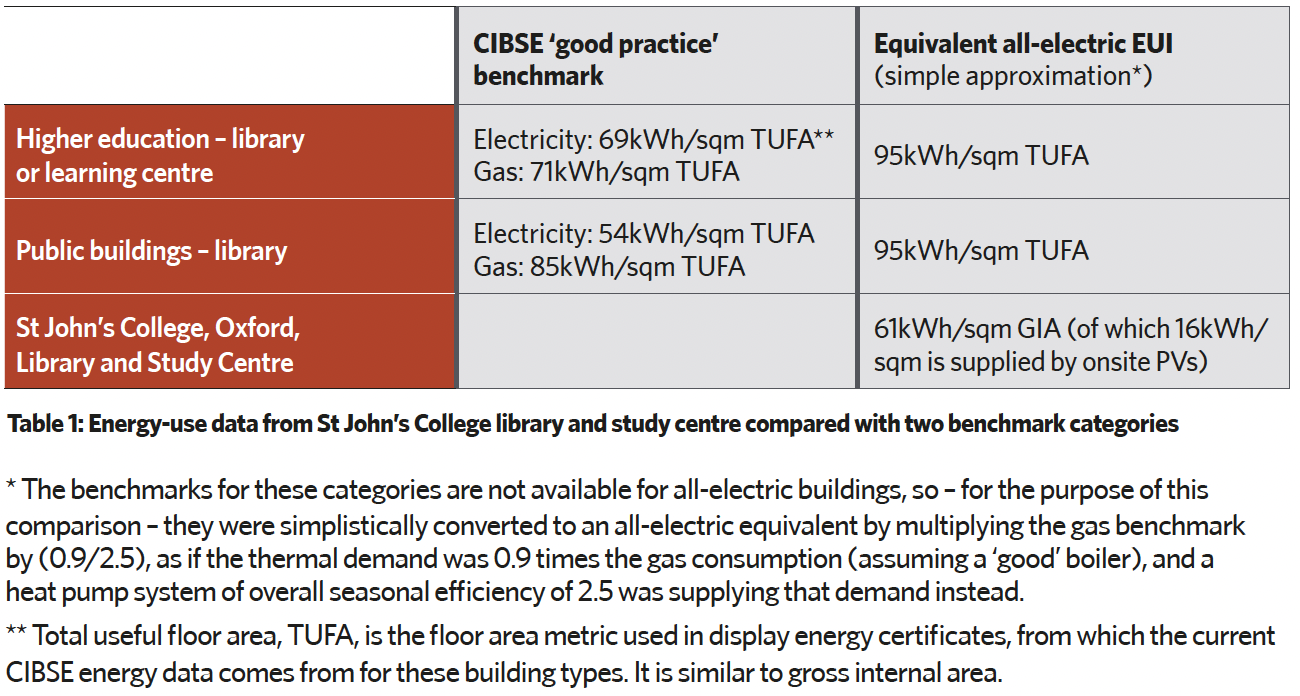

The energy-use data should still be viewed with caution, as occupancy patterns are likely to have been affected by the pandemic, but it compares well with benchmarks (see summary, compared with two possible benchmark categories, in Table 1).

Entries for the 2023 awards open this month (June). Do contact the CIBSE technical team if you have any questions or comments about the entry forms, or would like to contribute project exemplars to inform industry net zero targets.

Key changes for entries to 2023 Awards

- Contribution from onsite systems to become ‘essential’ information, providing the project’s total energy use

- Air permeability to become ‘essential’

Entrants will still be able to state if information is available.