A LEV system prevents fumes from entering a worker’s breathing zone

Every year, around 12,000 people in the UK die from occupational lung disease, according to the HSE, and there are around 18,000 new cases of individuals with breathing and lung problems.

HSE investigations reveal the human cost of exposure to hazardous substances – in the form of dusts, mists and fumes – which can lead to respiratory illnesses, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. One school cook developed breathing problems after working with flour in a school kitchen that was small and had no ventilation or controls for the dust flour. The 46-year-old retired early with severe asthma and was awarded £200,000 damages .

Another worker developed occupational asthma after inhaling solder fumes at a company in Gloucester. The company failed to install fume-extraction equipment to remove dangerous rosin-based fumes from the workroom air and, as a result, was fined £100,000 with £30,000 costs. The employers were prosecuted under Control of Substances Hazardous to Health 2002 (COSHH), which requires employers to control substances that are hazardous to health.

Many cases of occupational illness could have been avoided if proper measures had been taken to reduce workers’ exposure to hazardous substances. Local exhaust ventilation (LEV) equipment is designed to reduce the exposure of workers to these deadly hazards, which can accumulate in the body for many years before an illness is diagnosed.

Best practice guidance

To ensure best practice in the design, installation, operation and maintenance of LEV systems, BESA and the Institute of Local Exhaust Ventilation Engineers (ILEVE) – a division of CIBSE – have produced TR40: A guide to good practice for local exhaust ventilation.

TR40 is aimed at everyone in the supply chain involved in the design, installation, operation and maintenance of local exhaust ventilation systems. These include employers, designers, suppliers, project managers, LEV commissioning engineers, employer-appointed LEV responsible people, LEV trainers and all other employees who design, commission, operate and maintain LEV systems.

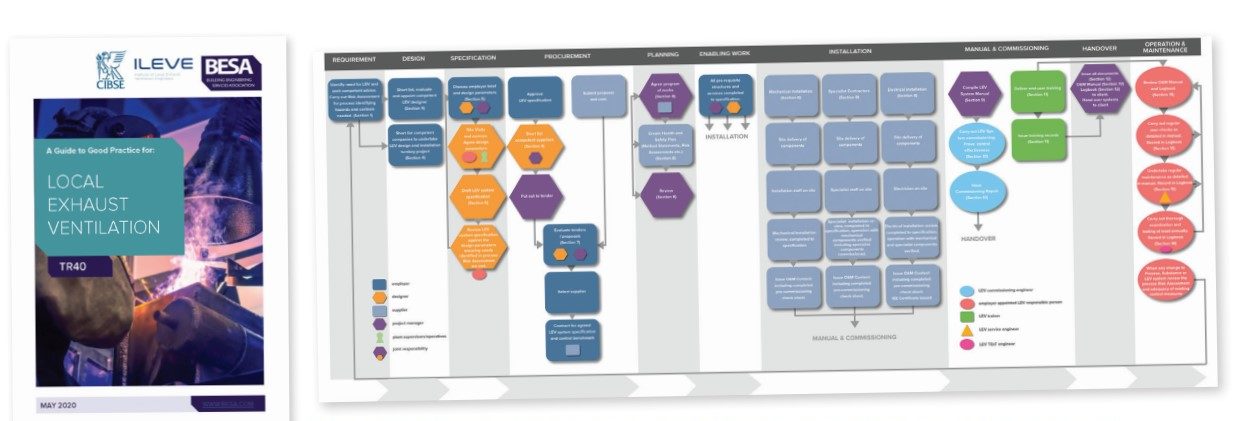

There is information on the various LEV roles and associated legal and statutory responsibilities. The document outlines what people should do and when they should do it, to ensure the LEV process – from start to finish – provides effective solutions to control exposure to hazardous substances. Roles and responsibilities are detailed in a diagrammatic form at the start of TR40 (Figure 1).

The guide describes the components of a LEV system, which includes hoods, ducting, filters, air mover and a discharger. LEV systems all work in the same way; airflow into hoods carries the dust or fumes away to a filter, which removes them. They may be portable or fixed, and include microbiological safety cabinets, dust-extraction units, spray booths, fume extraction, fume cupboards, down-draught tables, and on-tool extraction units.

There is a detailed section in TR40 on identifying competency, which explains what skills, experience and knowledge and training to look for. It also highlights the importance of keeping records and makes clear what to ask when evaluating LEV tenders and quotations. It explains that the employer must ensure their advisers, and those they employ for specific roles to undertake works associated with LEV systems, are competent.

Figure 1: The TR40 guidance has a clear, diagrammatic description of the roles and responsibilities of those involved in delivering LEV

The guidance outlines the competencies required for LEV designers suppliers, commissioning engineers, maintenance engineers, installation contractors (mechanical, electrical and specialist), and the thorough examination and test engineer. For example, the designer should be able to demonstrate competence in designing effective LEV systems. They should be a member of a relevant professional body and have proven competencies in the fields of occupational hygiene and LEV engineering design.

It also explains the role of the occupational hygienist if a risk assessment is deemed necessary to monitor employees’ exposure to hazards and evaluate the performance of control measures in place.

There are questions employers should ask members of the supply chain. For example, how did the designer show that the LEV provided adequate control, and have there been any operational issues since installation.

Section 4 features the employer brief and design parameters. The brief for the designer contains the requirements for the system. The designer should visit the site to observe the operation of the process if possible and this may influence the control options available.

Section 5 features a checklist for the LEV system specification. There are 26 items, including: details of the processes and hazardous substances to be controlled; the agreed controlled benchmark to be achieved, with the relevant occupational exposure limits; and information about hoods, ductwork, test points, filter, air mover and motor, controls, make-up air and maintenance access.

The designer should have proven competencies in the fields of occupational hygiene and LEV engineering design

Evaluating LEV tenders and quotations is in section 6. The key guarantee required is that the LEV will adequately control the hazardous substance to an agreed benchmark. Other areas to check are the competency of the LEV supplier, specification and installation compliance, essential documentation, and whole-life system costs.

There are sections on installing, commissioning and maintenance, and TR40 explains how LEV commissioning differs from normal plant commissioning, as it has to ensure the operator’s safe use of the system.

Section 7 describes the installation programme, and states that an outline project programme should be developed to identify key tasks, critical dates and milestones.

Best practice for an operations and maintenance manual is described in Section 8, while Section 9 focuses on how commissioning should be carried out. It says the report should include measured exposures from the breathing zone of the operator to identify whether the LEV: is controlling exposure to the hazardous substance adequately; is matching the specification; has been correctly installed; and is being used correctly. The final four sections discuss training, the log book, handover documents and thorough examination and testing.

TR40 should be read in conjunction with the HSE publication HSG258 – Controlling airborne contaminants at work – A guide to local exhaust ventilation, which offers employers further guidance on the design of new local exhaust ventilation (LEV) equipment.

TR40: A guide to good practice for local exhaust ventilation is available from the CIBSE Knowledge Portal.

TR40 expert panel: Jane Barstow, Rob Mackay, Adrian Sims and Phillipe de Wilde

People die if you don't get the design right

Adrian Sims is passionate about raising the profile of local exhaust ventilation. As an expert witness in HSE prosecutions, he has seen the devastating effects on people’s

health when organisations fail to provide adequate protection from the inhalation of hazardous substances.

In a recent case, a former soldier inhaled oil mist while at work on one occasion, resulting in a serious respiratory condition that led to him losing his flat and girlfriend.

‘That’s how serious this is – it destroys lives,’ says Sims.

TR40 is designed for people in the LEV contract chain. HSE already has a guidance document, HSG258, aimed at the owner of the system; TR40 looks at how designers,

installers and commissioning engineers protect the person at risk.

‘When you look at occupational exposures and who gets hurt, it tends to be the low-skilled worker, who doesn’t know that wood dust gives you cancer,’ says Sims. ‘A huge education piece has to be done, from top to bottom. It needs to be treated with care. If we don’t get the design right, people die.’

Sims says he is asked by contractors to design LEV systems without being told exactly. what is having to be extracted from the space. ‘They say it’s just an extraction system, just get on with it. They don’t appreciate the issues. Wood dust gives people cancer – it’s an asthmagen and a carcinogen.’

■ Adrian Sims is managing director at Vent-Tech and director at WorkSafe Design.