Hoare Lea’s socially distanced desks are arranged to suit the air distribution

After the recent rise in Covid-19 cases in the UK, the government has recommended office workers who can work effectively from home should do so over the winter and only those that are unable to work from home should go to the office. The work undertaken to our office means that we can welcome back staff into a COVID secure environment if they need to come in.

Foremost in our minds when making our office Covid-secure was creating a calm, reassuring space that was productive. We wanted the office experience to be as close to that of the pre-Covid workplace, while being as safe as possible.

The first step was a survey to discover how people felt about returning and how they were working at home. This information was invaluable, leading us to conclude that any return to work should be on a phased basis, with only those struggling to work from home – because of IT issues, home conditions, and so on – invited back in our first phase.

The distance dilemma

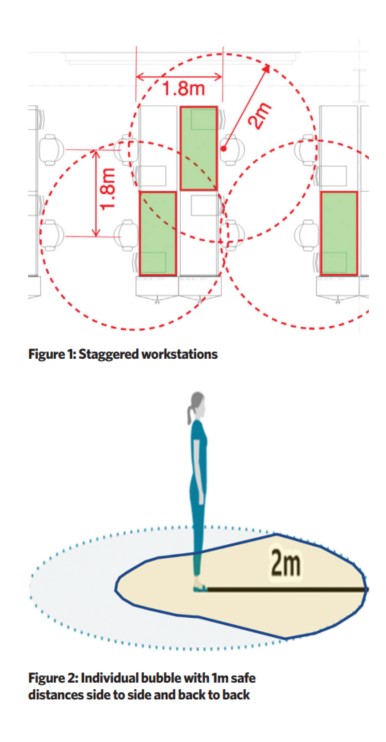

Most modern offices, including our London one, use straight workstations, where employees sit about 1.8m apart, opposite each other, face to face. The government guidance emphasises 2m social distancing or 1m with risk mitigation where 2m is not viable. Not wanting to install a vast array of Perspex screens, we have used a staggered, diagonal, active workstation arrangement to comply with the 2m social distancing guidance (see Figure 1).

This, obviously, places capacity limitations on the reoccupation permitted. The government’s mantra is ‘follow the science’, so I was curious to read the supporting documentation behind the 2m guidance. The evidence is in a paper prepared by the Environmental and Modelling Group and published by SAGE in June 2020.

This paper does indeed detail ‘face to face’ safe distances of 2m where prolonged periods are necessary. However, it also details that the risk of 1m side to side or back to back carries the same risk as 2m face to face. This is not mentioned within the government’s guidance. If adopted within the guidance, the resulting planning bubble around an office employee would, I believe, be along the lines of Figure 2.

It is no surprise that following government guidance leads to office occupancies of around 30-45% without further intervention measures. If the government’s guidance was to fully adopt the ‘scientific evidence’, occupancies could increase – perhaps, up to 50%. Also, if the government was bold enough to lower the face-to-face distance to 1.8m, office planning occupancy levels may well rise above 75%. A dilemma, indeed, if we are to see numbers return to their office workplace.

Dilution

There is clear scientific evidence that dilution of indoor air with the introduction of outside air plays a crucial role in minimising the risk of airborne viral transmission.

Like most modern workplaces, our London office’s façades and roof do not have any opening windows or vents, relying upon a mechanical air supply system to condition the space and introduce outside air for ventilation. The office is environmentally conditioned using two dedicated air handling units (AHUs) that serve underfloor variable air volume (VAV) boxes to independently controlled zones over two floors.

Installed in 2012, the AHUs use a recirculation air cross-connection between supply and exhaust to recover energy from the office while maintaining a design minimum outside air supply of 1.32L.s-1·m-2 during times of very high or very low external enthalpy. They include mixing dampers to regulate and provide free cooling/heating at times when the outside air permits.

Air supplied through floor grilles varies between 15L.s-1 and 40L.s-1

Air is supplied into the space, via underfloor plenums, through floor grilles. Each grille can vary in volume between 15L.s-1 and 40L.s-1. Given the injection of air at floor level, the desks are arranged to suit the air distribution and ensure comfort. The configuration was tested before CAT A design.

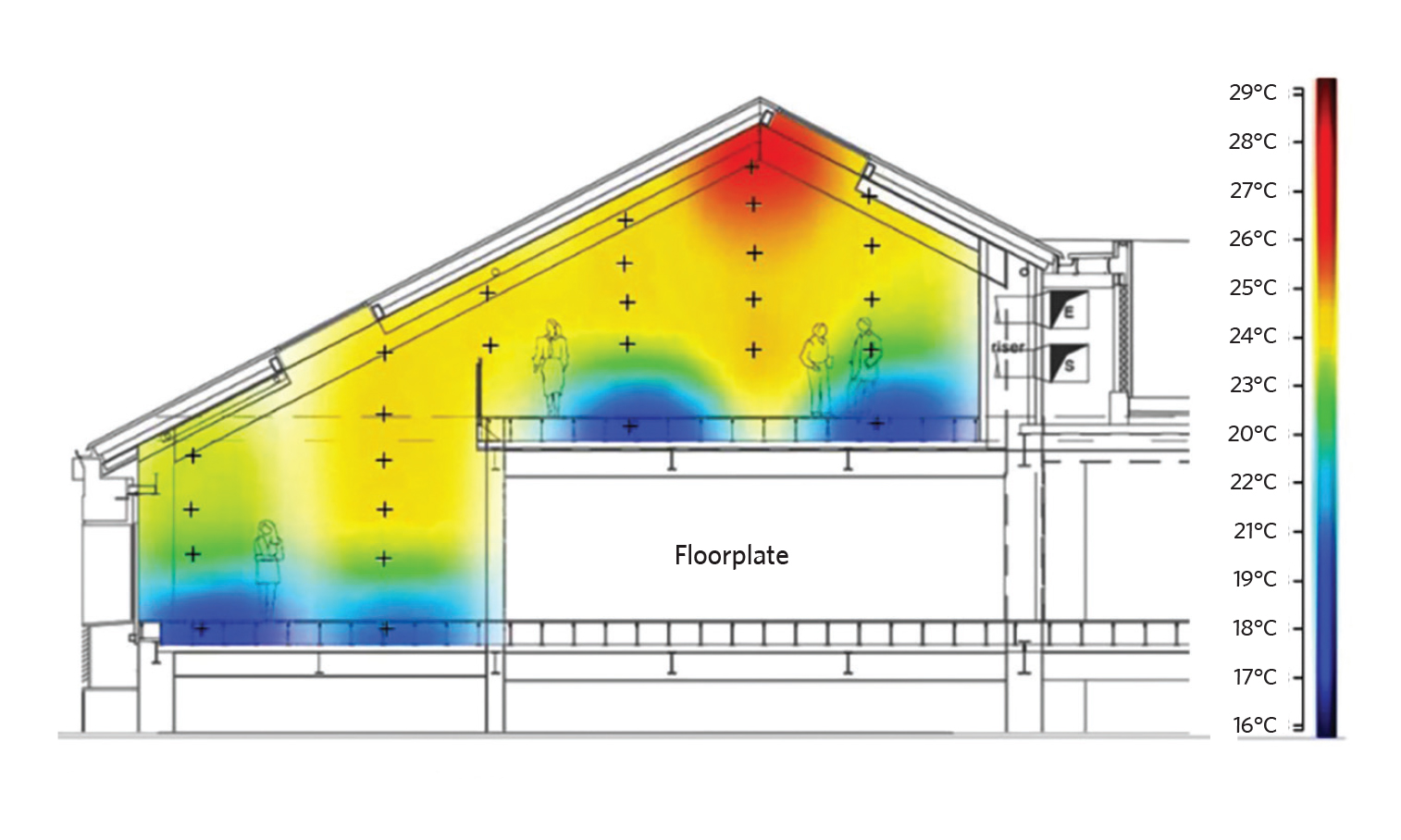

The characteristic performance of the diffusers means that, at 15L.s-1, the air injected into the space acts in a manner similar to that of a displacement air supply system. At 40L.s-1, the air is thrown vertically and mixes with the surrounding air, providing comfort conditions up to 2m height, with temperature then rising with height above 2m.

To prove the system in operation, we installed vertical arrays of temperature sensors located at the desk spines. A time slice of the space, taken at midday during high solar gain, can be seen in Figure 3, demonstrating the conditions achieved within the occupied zone.

Figure 3: Internal temperatures during occupation in August

As a firm, we have been monitoring industry reoccupation guidance closely and have our own Covid-19 technical support team. It offers advice to our clients who are looking to ‘re-energise, reoccupy and rethink’ their premises.

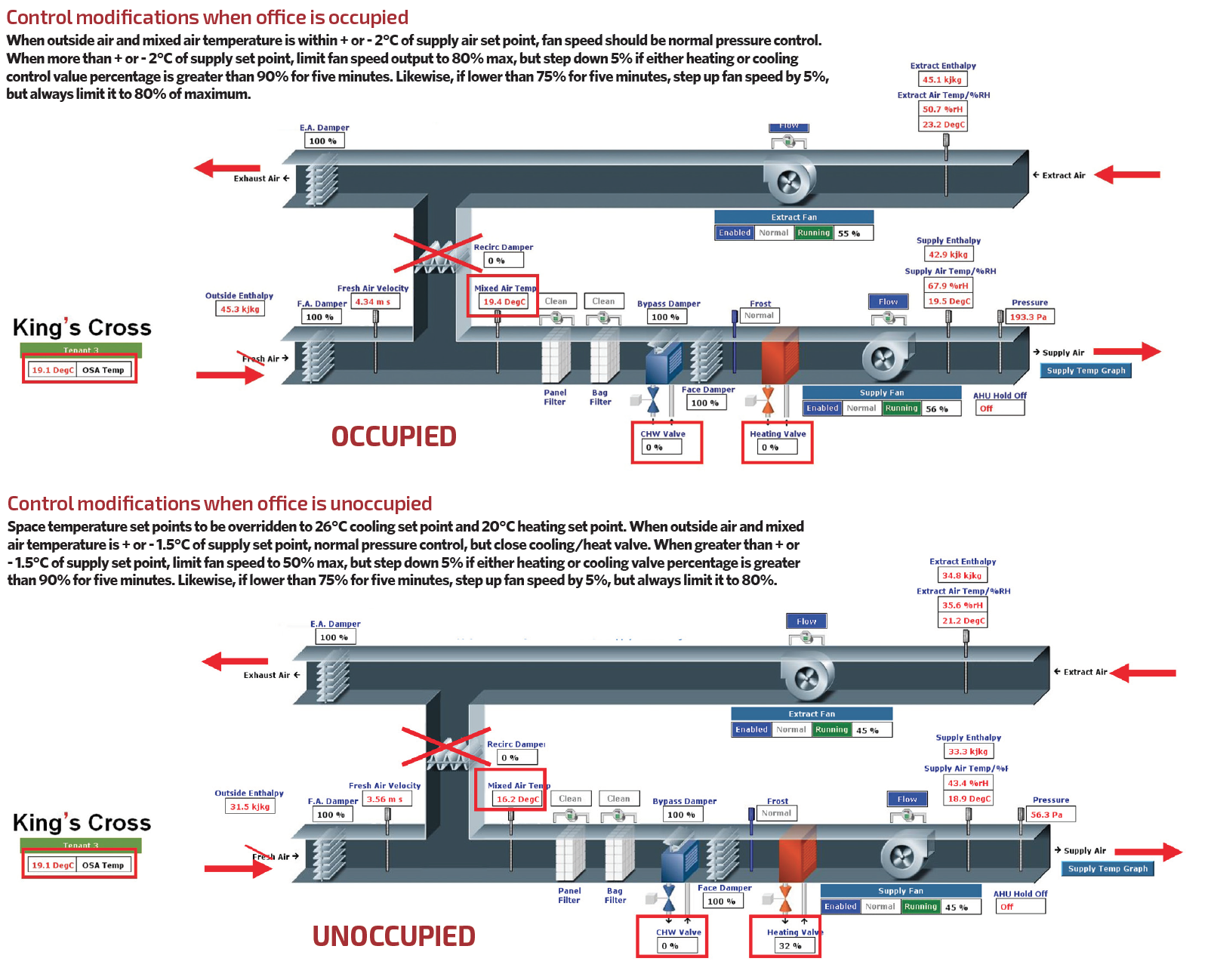

Following CIBSE and REHVA guidance, recirculation needs to be isolated and the ventilation is recommended to be run 24/7. This creates challenges in how the supply air could be controlled within the capacity limits of the heating and cooling coils.

The AHUs are owned, operated and maintained by our landlord. One of the fundamentals of any Covid-19 reoccupancy plan is to understand fully how ventilation air is supplied into your office and how much is delivered. Cooperation and liaison with the landlord is a must. Knowing our systems well, we knew that supplying an increased amount of outside air into the space was not an issue; it was more about how the supply air was to be maintained at around 19°C without the heating and cooling coils being overwhelmed.

The solution involved a series of control interventions that respond to outside air conditions, and whether the office was in occupation or not. The images on page 36 show the successful implementation of the controls modifications. As the AHUs operated on the demands of static pressure to satisfy the zonal VAV boxes, speed control of the fans had to be implemented to allow the coils to temper the air to the set temperature, recognising that the desired supply duct pressure may drop at very high or very low ambient air conditions.

During unoccupied periods, the controls interventions permitted a greater period of time when neither the heating nor cooling coil were energised, while also lowering the fan speed to lessen the amount of outside air being provided. The observed flowrates at night are above the normal minimum outside air supply design flowrate and around 20 times that recommended within the REHVA guidance of 0.15L.s-1·m-2 during unoccupied periods. Stable fan speed operations limit the minimum supplied volume.

As the AHUs operate under a variable air volume control, the units have outside air intake velocity measurements to ensure the desired minimum design outside air flowrate is maintained. This is reassuring to have, as it provides a means to monitor flowrates.

All the above is logical in principle, but how do you prove, in practice, that the office space is ventilated to a high level to reassure employees that the environment they occupy for long periods of time is of good quality? The answer lay with the installation of air-quality monitoring within the space. CO2 monitoring is known to be a very good indicator of how well indoor air is diluted with outside air. Since 2016, we have used our office as a ‘Living Lab’ to demonstrate and test bed new technology, to continually evaluate the post-occupancy performance of our spaces. As part of this, we have multiple sensors around the office, including for air quality.

The air-quality sensors’ data are collected constantly and reported via our in-house app, which displays trend logs of the conditions. At the time of commissioning the new AHU control interventions, the app showed a climb in CO2 when the supply air was interrupted to the space. The sensitivity and response to ventilation being cut is very quick and is a cost-effective way of reassuring employees of the ventilation rates within the space.

Reopening offices to employees following government guidance is not as easy as one would think. The airborne transmission route of Covid-19 is by far the greatest challenge to understand and to minimise, especially with the ever growing prevalence of those who are asymptomatic.

At this moment in time, the ventilation of indoor spaces has never been so important to understand, control and monitor.

About the author

Steve Wisby is a partner at Hoare Lea