Timber Square was the first project to be awarded a Nabers UK design target rating

The widespread disclosure of operational energy in UK buildings has taken a big step forward this year, with large commercial developers awarded Nabers UK ratings.

Landsec was the first in the country to achieve a design target rating for its proposed Timber Square office development in Southwark, which received a five-star rating in February, while Grosvenor’s 87,500ft2 Toronto Square building in Leeds has achieved the first Nabers UK rating for an existing office building. It was given 4.5 stars after 12 months of data was analysed by licensed assessor EP&T Global and independently certified by BRE.

Nabers measures and verifies the actual energy use of commercial buildings, and awards offices a star rating of between one and six. The scheme was imported from Australia, where it has been used for more than 20 years, and where a recent report found that buildings benefited from an average 42% reduction in base building energy intensity after the 14th Nabers rating.

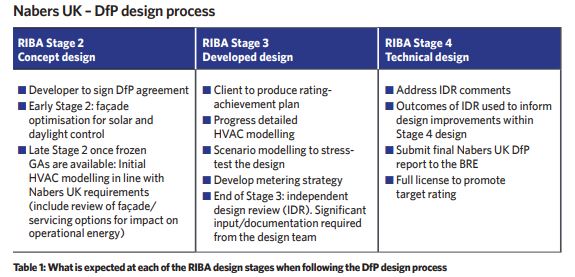

The two rating systems for new and existing buildings are called Nabers Design for Performance (DfP) and Nabers Energy respectively. Nabers recognises buildings at the design stage by awarding a target rating after an independent design review (IDR) (See panel, right). Since the start of 2022, seven developers have achieved design target ratings for their projects.

The DfP process commits owners to design, build and commission a new development, or major refurbishment, to achieve a specific Nabers UK energy rating (See panel, ‘Design for Performace process’).

Landsec’s Timber Square is an ambitious 335,000ft2 development comprising two office buildings plus ancillary retail/leisure uses. The scheme consists of the 15-storey new Ink Building and the 10-storey Print Building, which is a refurbishment and extension of an existing building.

Hoare Lea was involved from project inception and provided building services engineering and a range of other disciplines, including sustainability, acoustics and fire.

There was a clear brief from Landsec that Timber Square would use modern methods of construction and circular economy principles to minimise embodied carbon emissions, while also targeting ambitious levels of operational energy performance.

The response was to partially reuse the existing structure of the Print Building and implement a hybrid steel and cross laminated timber (CLT) structure, resulting in an embodied carbon intensity of about half that of a typical London office.

A report found that buildings [in Australia] benefited from an average 42% reduction in base building energy intensity after the 14th Nabers rating

A baseline energy performance target was established at the early stages to achieve the UKGBC’s whole building office energy consumption 2020-2025 target, but with an aspiration to meet the 2025-2030 target and achieve a Nabers UK 5-star rating.

Although Nabers UK had not been formally launched when the project started, Hoare Lea were ready to implement the process using experience gained on early pilot studies across the different RIBA stages (Table 1) as one of the very first DfP Delivery Partners. .

At RIBA Stage 2 Hoare Lea worked closely with architect Bennetts Associates to optimise the façade for solar and daylight control. Hoare Lea’s analysts carried out parametric simulation using in-house tools to determine the optimum glazing configuration for each 6m façade bay. Each bay consisted of a mixture of solid, translucent and clear glazed panels – which could be used in combination to limit cooling loads while still achieving good daylight levels (in line with the Well standard) across the floorplate.

THE IMPORTANCE OF AN INDEPEDNENT DESIGN REVIEW

The Design for Performance (DfP) process starts with developers signing a DfP agreement, which states the target energy rating their building is aspiring to achieve. The building is designed, and a model and simulation report is prepared for an independent design review (IDR).

Once the IDR has taken place, a report is submitted to the BRE. When the report is approved, the developer can promote its target rating. After completion, a Nabers-accredited assessor carries out an assessment based on 12 months of energy data, to demonstrate whether the target has been met.

The two most pioneering elements of the DfP process are the IDR and the detailed dynamic energy-simulation modelling, according to a report presented at the 2022 CIBSE Technical Symposium.

In Design for Performance: Lessons from the Nabers UK independent design review process, the authors say that the modelling of building services systems and controls is particularly important.

The IDR identifies whetehr the design for the base building is likely to meet its operational target. IDRs can be undertaken at multiple stages of the RIBA Plan of Works, though the DfP Guide recommends that an IDR be conducted during Stage 4, when there is sufficient design detail to produce simulation.

The authors recommend that the model be updated and revised in parallel as it progresses from Stages 2 to 5, and a feedback loop put in place from the model to the design team. At Stage 5, the focus of the simulation should be post-construction monitoring and tuning, they add.

Since the start of their review in 2020, the authors observed increasingly sophisticated building simulation models that were leading to more realistic models

During concept design Hoare Lea also carried out initial HVAC modelling to evaluate different design options, for example comparing fan coil units (FCUs) to active chilled beams, and mechanical ventilation to mixed-mode ventilation.

At RIBA Stage 3, detailed HVAC modelling was carried out using IES thermal modelling software and the ApacheHVAC module, including scenario modelling to ‘stress test’ and refine the design.

The sophistication of the software meant that Hoare Lea could model a large number of variables such as ventilation airflow rates and supply temperatures, fan and pump efficiency curves, ductwork heat losses and gains, demand control ventilation, FCU operation (variable temperature and flow), air source heat pump (ASHP) temperature and load dependant performance, plant sequencing and heat recovery to align with the engineering design.

The richness of the data enabled a level of outcome-focused decision making that would not have been possible otherwise. For example, the HVAC analysis informed the decision to have three heat pumps per building rather than two. Having two would have led to one of the heat pumps running for longer periods at low loads, which would have affected plant efficiency and energy consumption.

Two on-floor climate control options – fan coil units (FCUs) and active chilled beams – were also modelled, says Henry Burrows, lead mechanical engineer for the project.

‘As the active chilled beams rely on central ventilation to meet the cooling load, we couldn’t utilise the full benefit of demand control ventilation with this solution, which is a key benefit in a post-Covid environment. The FCUs would not conflict with the demand control ventilation, so they were the preferred option,’ he says.

In a Part L or TM54 model, you have an estimation. With Nabers you have a huge amount of data, and its granularity means you have more information to evaluate

Modelling influenced the DHW strategy for the office WCs, leading to the selection of electric point-of-use water heaters after they were compared to a central hot water system connected to the ASHPs.

While incredibly powerful, the modelling required is complex. ‘With Nabers quality advanced simulation you have information on every level, and every change affects everything.’ says Owen Boswell, Nabers UK assessor and simulation lead for the project.

‘In a Part L or TM54 model, you have an estimation. Nabers is now the gold standard. You have a huge amount of data, and its granularity means you have so much more information to evaluate.’

However, Boswell says there is an acute skills shortage in this level of modelling in the UK, which Hoare Lea has been tackling through training and global knowledge sharing, as part of its net zero strategy.

A firm-wide working group made up of representative of all disciplines ensures that lessons learned across Nabers projects are translated to every project in the firm through guidance and specification updates.

‘There haven’t been the industry drivers to implement this level of modelling at scale in the UK over the last decade. Nabers UK

and the drive towards net zero is the prompt to upskill. The talent and enthusiasm is there, but it’s a steep learning curve initially,’ says Boswell.

CIBSE provides training courses on Advanced Simulation Modelling for Design for Performance. For more details visit bit.ly/CJAug22Nab1

Technical risks:

The authors of a paper on Nabers independent design reviews1 have identified technical risks that could affect target operational ratings – and have offered potential solutions

Heat-recovery variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system Zonal thermal diversity tends to favour heat-recovery VRF systems. With smaller VRF buildings delivered as a shell-and-core base building design, stress test poor design by the tenant by removing the diversified internal zone loads.

Water-to-air heat pumps Unless enforced via tenant leases or a CAT-A HVAC design, any condenser water valves for the compressor units are likely to be open for long durations. This will lead to the pumping system acting as a constant flow, instead of variable flow, system. This risk is mitigated if continuously modulating condenser water valves linked to compressor load is specified.

Air-to-air heat pumps Where a single heat pump serves interior and perimeter zones with terminal reheats, the high efficiencies of heat pumps in heating mode is not capitalised, and reheat energy will be high. This is because the heat pumps will operate to satisfy the warmest zones, leaving any colder zones to be reheated using terminal reheats. Where this result is not observed in the simulation results, revisit how the air transfer between HVAC thermal zones is modelled by the simulation software engine, or consider adding internal partition walls to ensure this is modelled correctly. From a mechanical design perspective, this system should be designed with separate perimeter and interior zone heat pumps.

Centralised cooling and heating plant Standard designs seem wedded to the use of plate heat exchangers at each tenancy for hydraulic separation. This practice is advantageous to enable tenant fit-outs without affecting the broader hydronic network and pseudomonas risk management.

However, this is at the expense of pressure losses across the heat exchanger (typically between 10kPa and 40kPa) and, more notably, restricts execution of temperature resets that increases chiller and heating plant efficiency during building partial loading. As a result, the system regresses to operating as a constant temperature system, which can perpetuate the ‘low delta T’ syndrome. While uncommon, some projects did specify a design without plate heat exchangers, suggesting that the alternative configuration without them, the Australian norm, is possible in the UK.

Related to the above issue is the practice of domestic hot water (DHW) calorifiers and space heating sharing the same LTHW plant. Space heating demand is seasonal, while DHW demand is steady-state across the year. The common issue observed was domestic water temperature requirements restricting the ability for the LTHW temperature to be reset downwards when space heating demand is low. Designs should consider the ability to service the DHW load separately from the centralised plant (for example, via a separate hydraulic connection to a dedicated heat pump) or, at minimum, a separate hydraulic riser for DHW, so it is not on a riser shared with space heating.

References:

- Design for Performance: Lessons from the NABERS UK independent design review process, Foo, Bannister, Cohen, CIBSE Technical Symposium, April 22 Download the paper at bit.ly/CJAug22Nab2