This year’s UK summer has, so far, generally offered respite from the soaring temperatures seen in recent years. Last month’s mini-heatwave, however, is more like the hot summers that experts believe will be the norm in the near future.

Nine in 10 existing UK homes will be at risk of overheating if worldwide temperatures rise to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, which is baked in by 2050 if global warming continues on its current trajectory, according to a report published by Arup two years ago. The Climate Change Committee has said that nearly one-fifth of UK homes already overheat, even during cool summers. A warming climate is largely behind this, but the problem is often exacerbated by the way buildings are being made more energy efficient, by installing more insulation and making them airtight. ‘This issue isn’t going to go away; overheating is only going to get worse,’ says Jason Bennett, indoor air quality specialist at indoor climate solutions provider Zehnder.

To look into this growing issue, Zehnder and CIBSE Journal conduct research to get a better view of the understanding across the building industry when it comes to overheating. The majority of respondents were consultants (70%), followed by contractors (12%).

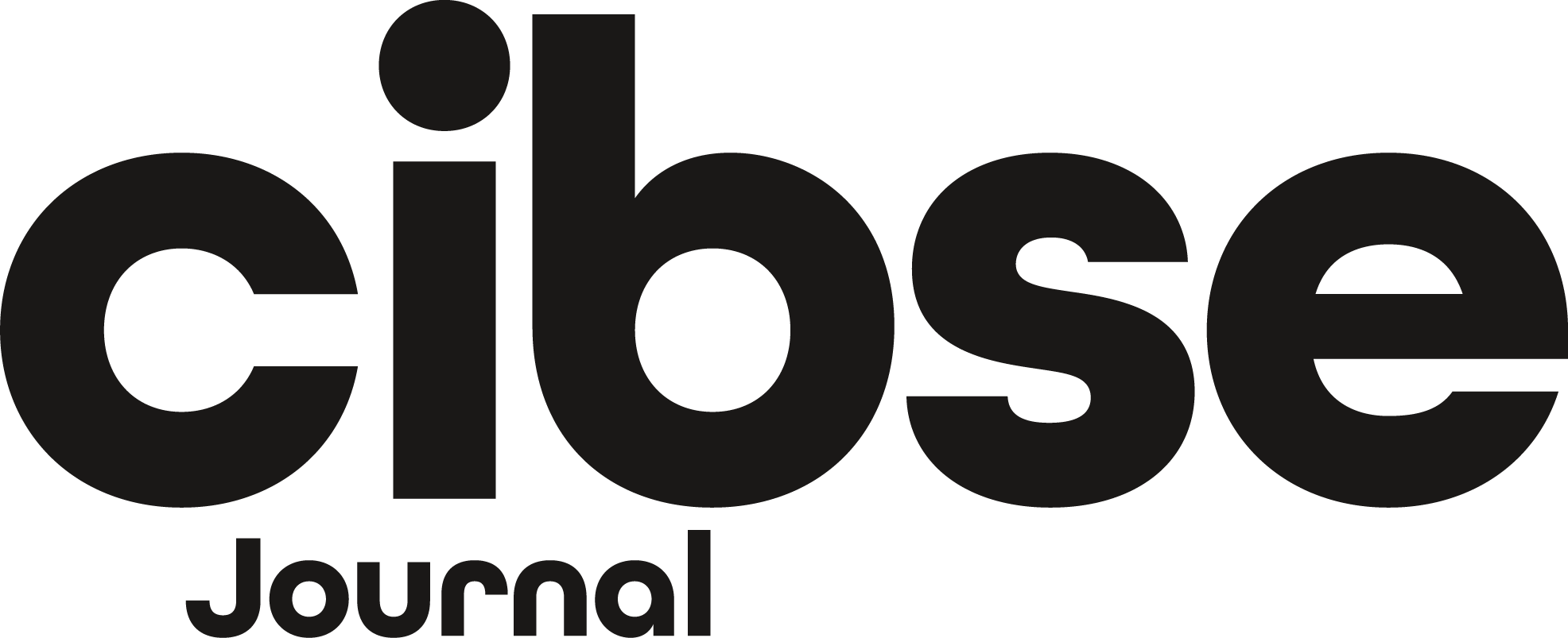

The findings show that, despite emerging evidence of overheating causing problems, the topic ranked relatively low on the respondents’ list of concerns. Asked to identify their priorities when getting involved in a new building project, they ranked design top, followed by quality, Building Regulations and energy efficiency. Modelling against the risks of overheating ranked eighth.

Asked what worried them most when planning a new building project, the top three concerns were, in descending order, design, cost and quality. Modelling against the risk of overheating ranked sixth in this list.

Bennett acknowledges that improved energy efficiency must continue to be a priority when designing new buildings, but ‘the future is about cooling’, he adds, pointing out that people’s sleep starts to be affected at temperatures of 24°C and above.

‘We create these really [energy] efficient homes and then spend a lot of money trying to reduce the temperature within those properties. We are creating hot boxes,’ he says.

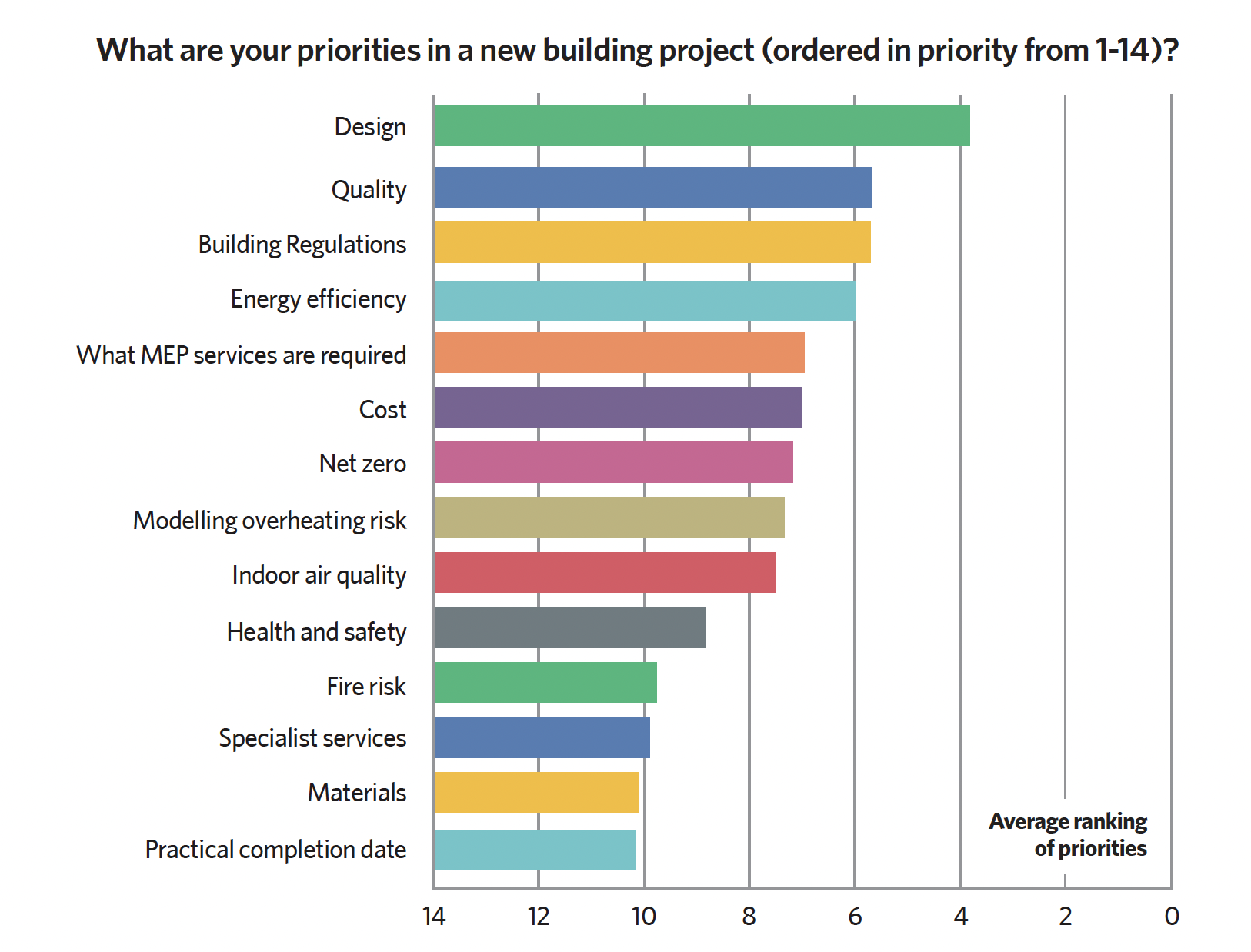

Insufficient awareness about the problem may be a reason why overheating is not higher up the industry’s list of concerns, the survey indicates. A third (34%) of respondents said they are familiar with Approved Document Part O of the UK Building Regulations, which addresses overheating in buildings, while 46% said they are ‘somewhat familiar’. However, a worrying 20% said they are not familiar with it.

Just more than one-third of the survey’s respondents said they know the Approved Document ‘inside out’, while 46% professed to understand the theory behind Part O, but were ‘unsure how to put it into practice’, and 19% said they ‘don’t understand it at all’.

This lack of understanding is ‘a worry’, says Bennett, who adds that the 19% may include contractors who tend not to get involved with specifying overheating measures, but will include others that do. ‘I would expect the consultants, developers, specifiers and architects to know about Part O,’ he says.

These groups of professionals should be ‘very familiar’ with Part O, which suggests that overheating should be more firmly embedded within the sector’s education curriculum. ‘It’s education, education, education,’ Bennett says, noting that Zehnder runs a programme of continuing professional development.

While the level of understanding about Part O could be better, Bennett says it is reassuring how the younger generation of engineers are more aware of its importance.

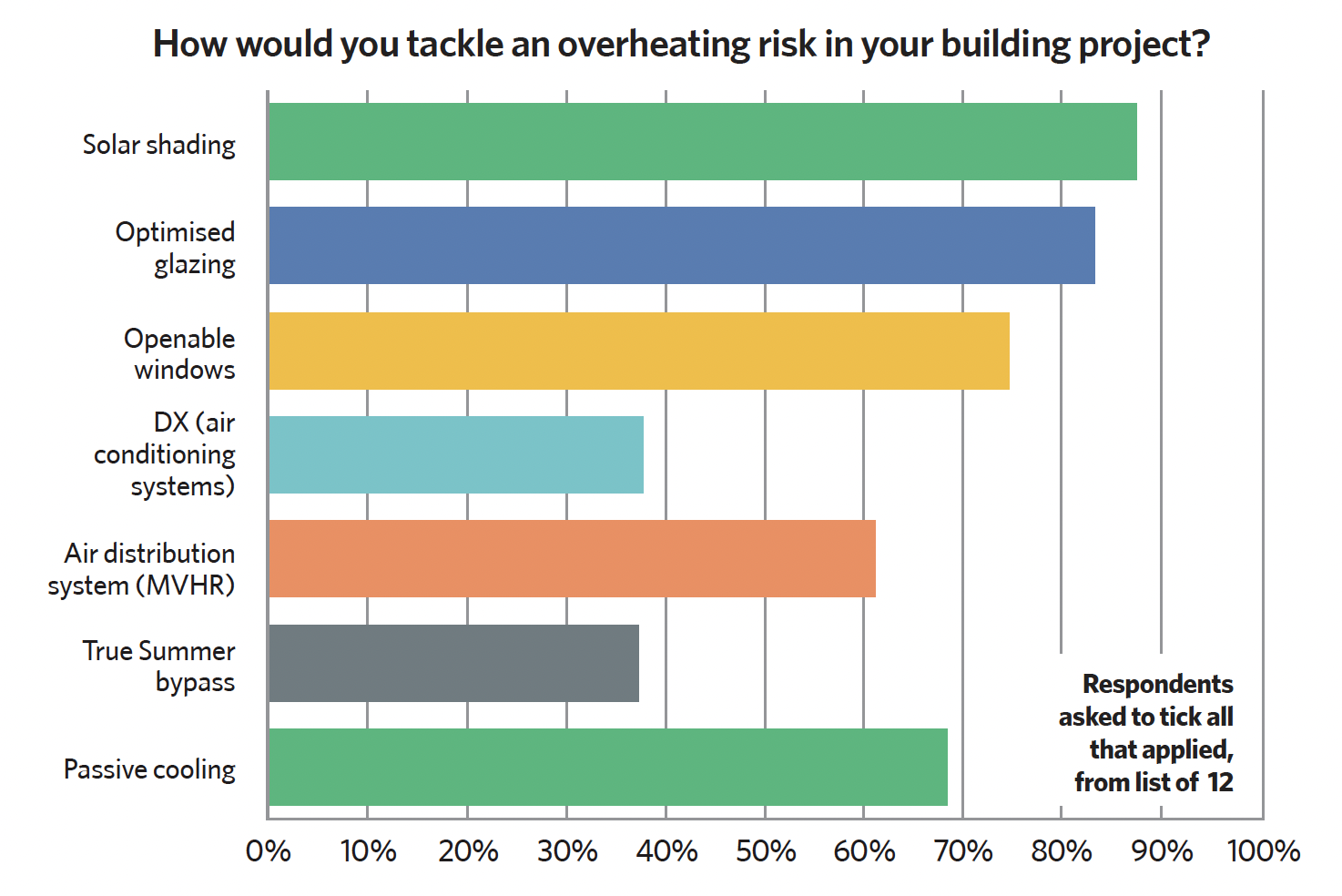

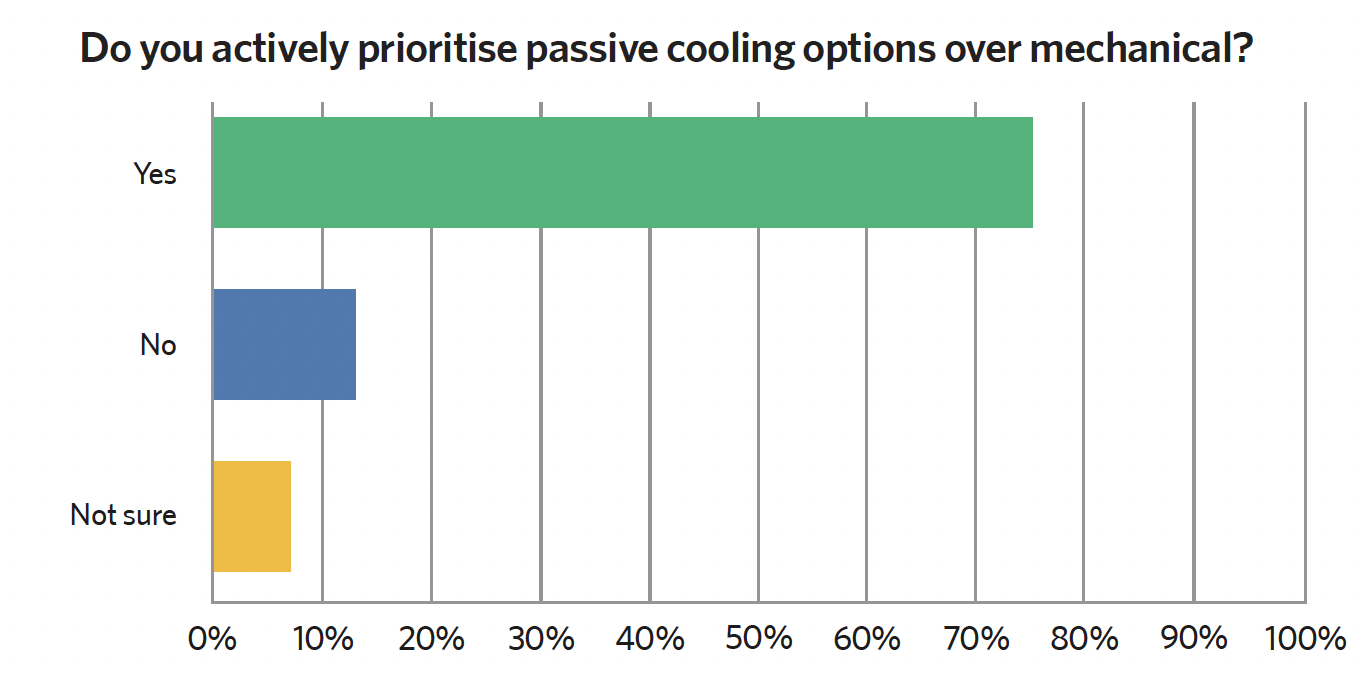

Nearly eight in 10 (78%) of the survey’s respondents said they actively prioritise passive cooling options over mechanical ones, with just 14% opting for the latter, reflecting the approach laid out in Part O.

Growing awareness of overheating

Dr Anastasia Mylona, technical director of CIBSE, isn’t too surprised that one-fifth of the survey respondents lack awareness of Approved Document O.

Many building services consultants and engineers also don’t come across overheating because of the specialised nature of their roles, says Mylona: ‘If you’re not doing overheating assessments, then you will not know a lot about Part O and how to comply with it.’

Engineers and consultants working in smaller teams are more likely to carry out Part O compliance calculations, says Mylona, who represented CIBSE on an advisory board that advised the government on the formulation of the regulation.

She says it must be looked at in the context of the much lower level of awareness about overheating just a few years ago: ‘Five or 10 years ago, nobody thought about it: That is a massive improvement that Part O has brought.’

One respondent said mechanical cooling should not be used as ‘a means of avoiding good design’, with another noting that, even if it is required, putting in passive measures first will reduce the need for such interventions. Bennett responds that ventilation and ‘air tempering’ systems, such as MVHR, will work in the background without the need for ‘much input’ from homeowners. He said mechanical cooling can be acheived with air conditioning, but this method simply circulates stale and dirty air. A better solution is to incorporate air temperation into an effective ventilation strategy. The difference is fresh, clean air supply all year round with heat recovery in the winter and cooling in the hotter months – promoting better, healthy indoor air quality (IAQ). Zehnder can help by providing relevant information, he says, adding ‘There’s lots of great resource in regard to educating the homeowner on our website.’

Another respondent noted that mechanical cooling is ‘more predictable and dependable’, and another said, it is not always possible to rely on passive measures due to boundary constraints. For example, in highly urbanised areas such as central London, where noise and air pollution prevent window opening, recourse to mechanical ventilation and cooling is ‘nearly inevitable’, they say.

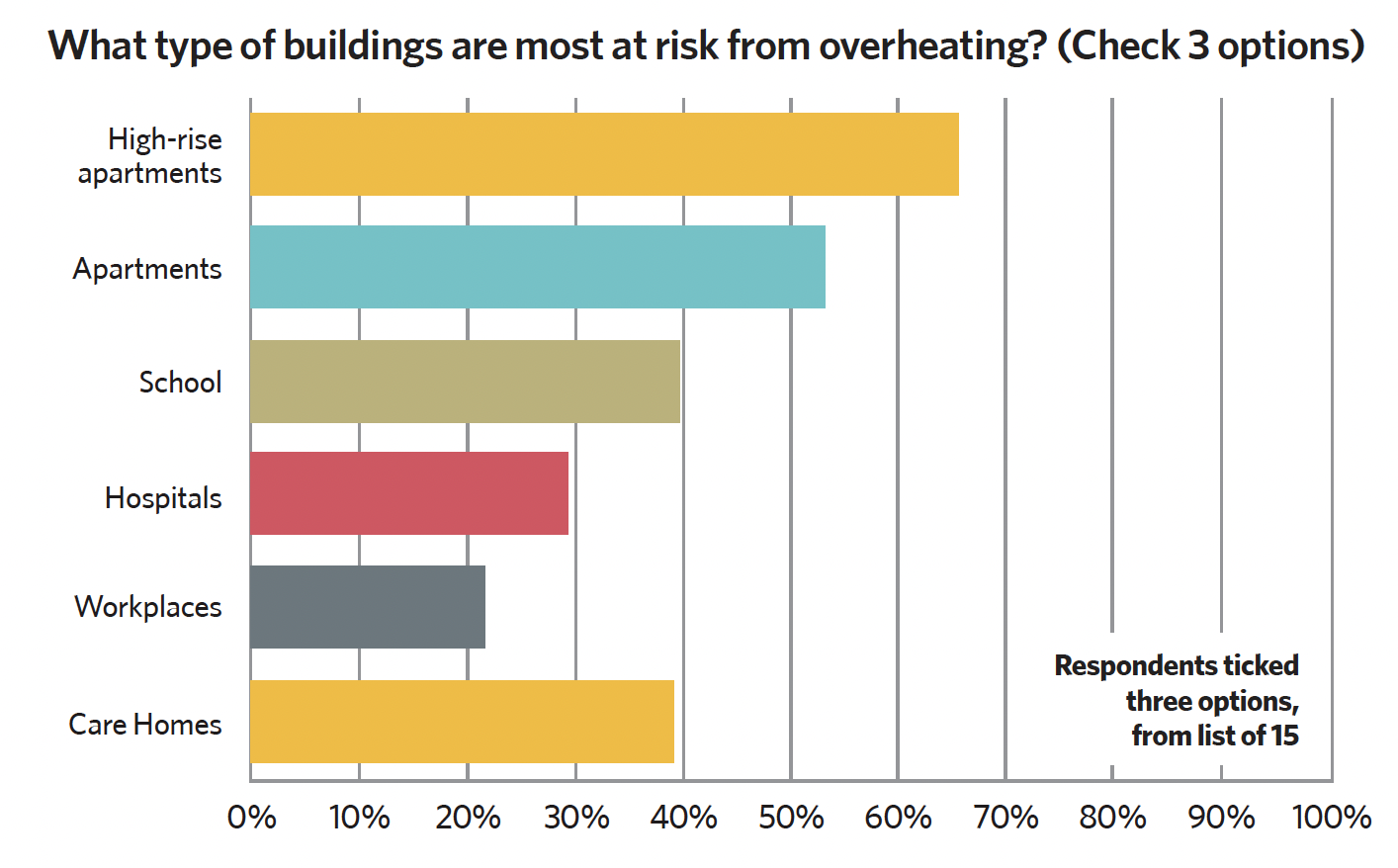

High-rise apartments were identified by 65% of respondents as the type of building most at risk from overheating. However, a significant proportion raised concerns about schools (40%), care homes (39%) and hospitals (30%). All of these building types cater for children and the elderly, who are among the most vulnerable in society.

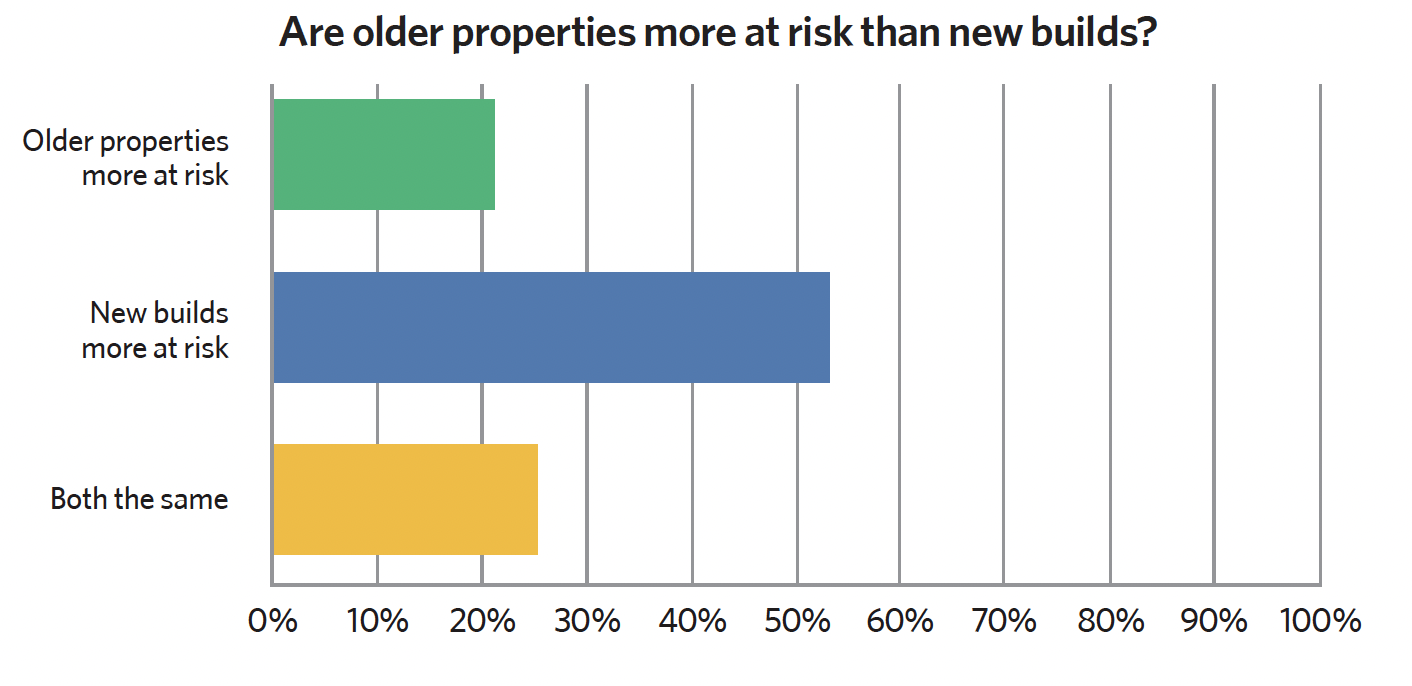

There were few concerns, though, about non-apartment type housing, such as terraced and detached homes. More than half of those surveyed (53%) said that new properties pose a higher overheating risk than older ones (21%). Respondents’ concerns about new buildings included lack of comfort for occupants, high glazing-to-wall ratios, non-openable windows, highly insulated properties and many flats being single-sided.

One respondent said: ‘Overheating in new buildings is a growing concern because of modern construction practices and climate change. The use of extensive glazing and high insulation for energy efficiency can trap heat, leading to uncomfortable and potentially hazardous indoor conditions. This problem is exacerbated by rising global temperatures and heatwaves.’

Many raised concerns about new-build properties’ lightweight structures and lack of thermal mass, with one respondent highlighting the ‘greenhouse levels of glass’ in some developments.

The top three solutions identified for tackling overheating were identified as solar shading, optimised glazing and openable windows. MVHR was identified as the fifth most popular solution, just behind passive cooling.

Several raised concerns about security, with one pointing to the risks of ground-floor openings. Bennett says, ‘the security risks, particularly on ground-floor apartments, mean that you can’t open your windows and doors at night-time when you would do normally and this is where a ventilation-based cooling approach is beneficial for the occupant.’

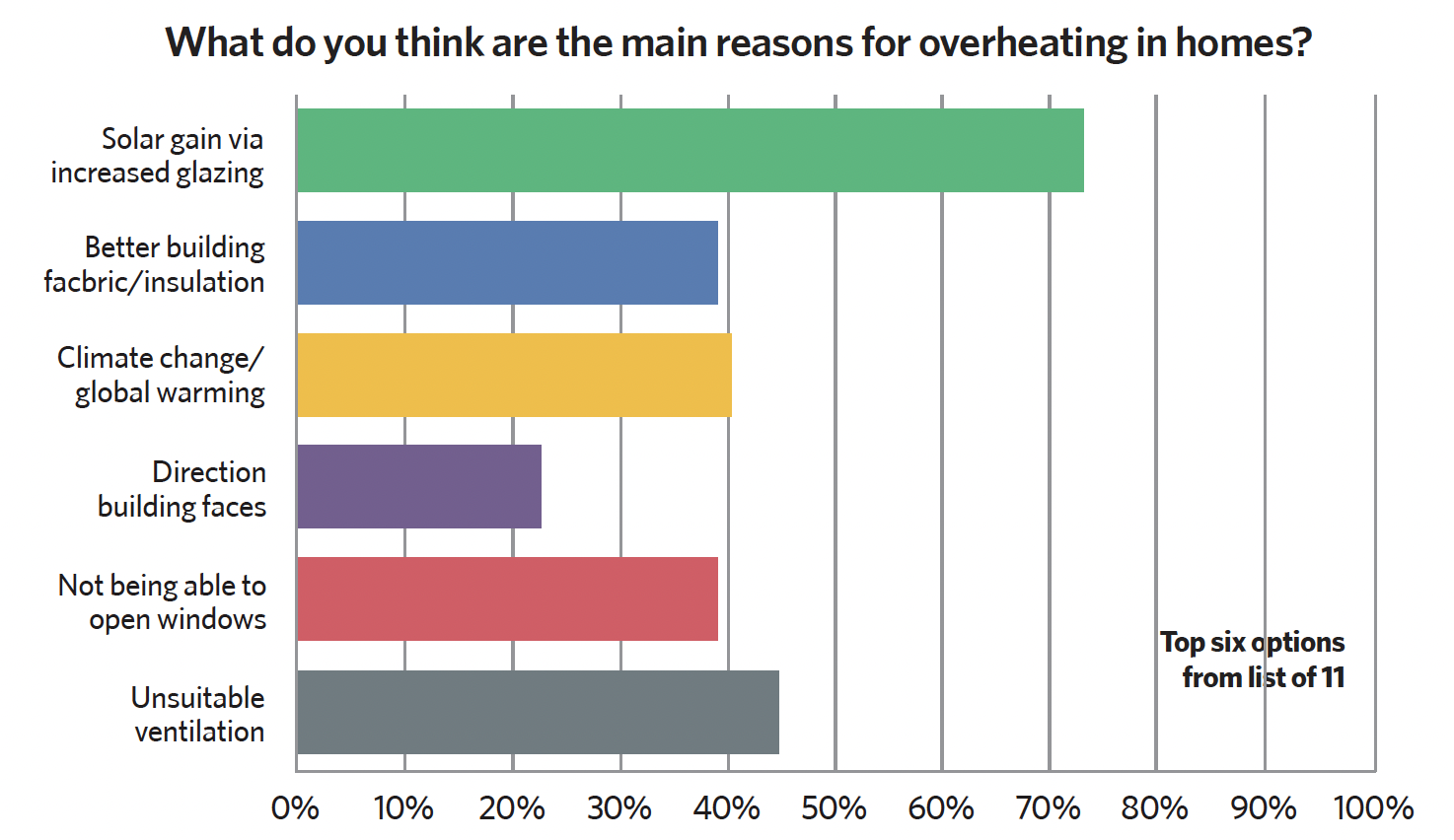

When asked what other methods or strategies they used to tackle overheating risk in their building projects, several respondents mentioned thermal mass and building orientation. A couple said ceiling fans, but very few respondents mentioned natural solutions, like planting trees on east and west elevations or using vertical shading. When asked to identify the main reasons for overheating in homes, most respondents named solar gain through increased glazing (73%). Jostling for second were unsuitable ventilation (45%), global warming (40%), not being able to open windows (40%) and more insulation (39%).

Zehnder always takes a holistic approach to ensuring that buildings don’t overheat, says Bennett: ‘Its principle is that thermal shading starts outside the building. You can’t do that in a high-rise, 15 floors up, but we talk about a fabric-first approach – for example, how many external shutters and how much passive shading you can have on the property.’

He adds that overheating needs to be designed out and thought about almost at the pre-planning stages. ‘We have to look at the dynamics of the building and we need to be coordinating our efforts along the way,’ he says, ‘and not just us, as an indoor climate solutions manufacturer – we should be networking and coordinating with the others responsible for mitigating overheating risks.

‘It’s great if I provide air tempering for your property, but if the sun is facing your window, I’m already fighting against 30 degrees.’

‘Creating a tolerable environment isn’t just about cooling and heating, but also about ventilation, an increasingly pressing topic as people spend a lot more time working from home post-pandemic,’ Bennett says.

CIBSE-funded research by UCL found that with home working much more attention must be paid to the health impacts of high indoor pollutant concentrations, and concluded that occupants should be made aware of the benefits of sufficient air-exchange rates and environmental control to enhance IAQ.

‘These systems are all cogs in the much larger machine of your home,’ Bennett concludes. ‘I’d much rather have a ventilation system that was filtering particles rather than capturing them in my lungs. I can change the filters – I can’t change my lungs. If it can also keep my property cool, it’s a win-win’.