Our walk takes us through a part of London being transformed by the addition of very tall buildings to a familiar, urban landscape consisting mainly of buildings of 24m or less.

While these new buildings in the City of London have energy management systems that are ‘state of the art’ – and are often treated as exemplars of modern design – there is a debate going on about how these constructions fare when in situ; that is, when surrounded by other buildings.

There appears to have been little consideration of the impact of these buildings, either on neighbouring structures or on the outdoor climate.

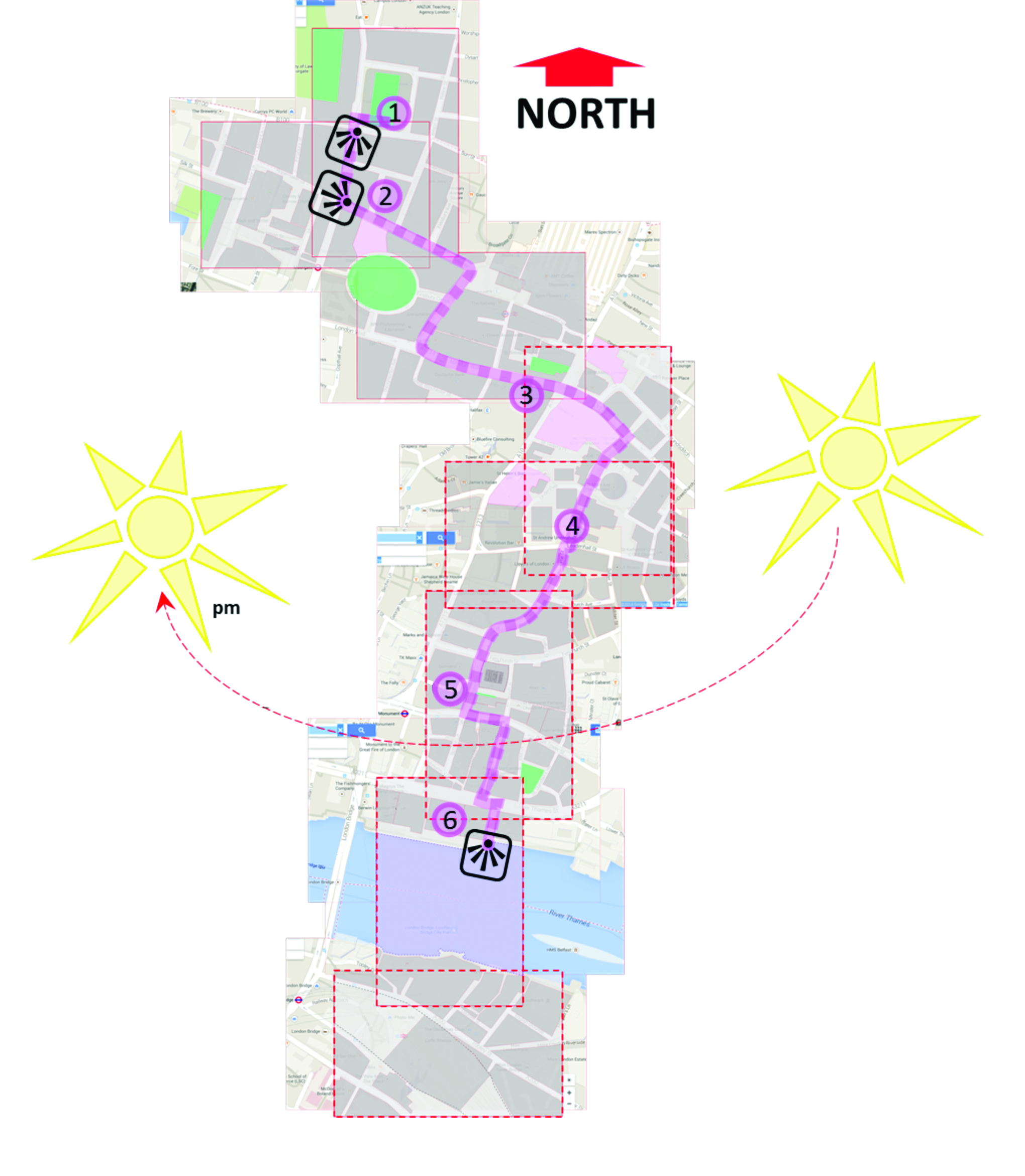

Our field trip takes a path from Finsbury Square, through the ‘eastern cluster’ of tall buildings, to the bank of the Thames. Walking this route exposes the pedestrian to a great range of microclimates created by the built landscape. Along the way, we observe the impacts of the changing landscape and speculate how the existing – and planned – buildings affect each other.

At the outset, it is worth reminding ourselves of a few controls on the climate at the Earth’s surface, and how decisions on built form and function can affect these. First, the intensity of solar radiation is controlled mainly by the altitude of the sun, which is a function of time and latitude. London lies at 51.5°N; New York, by comparison, lies at 40.7°N.

The effect of a building is to redistribute the available solar energy by intercepting the beam and generating a shadow at the rear. In cities, buildings vie for this resource, and create complex shadow (and reflection) patterns that shade – and may illuminate – open spaces and other buildings

Second, airflow near the surface of the Earth is greatly disturbed by the presence of buildings; in general, airflow near the ground is slowed in cities, but it is also more turbulent. A pedestrian will experience lulls and gusts, depending on the ambient wind velocity and on the dimensions and juxtaposition of building clusters.

Third, the fabric and structure of a city affects the heating of the near-surface air. Urban surfaces are generally dry, with little vegetation, so available energy is used to warm the overlying air, rather than to add moisture. Moreover, the urban surface is faceted, and each facet ‘sees’ only a portion of the sky; as a result, the city surface exchanges energy with itself and retains heat better than if it were flat (this is a major reason for the urban ‘heat island’ effect).

Finally, humans add heat and moisture – plus a host of air pollutants – to the urban atmosphere, mainly via buildings’ heating/cooling systems, and vehicles. As a result, urban areas have distinct climates, different in nearly every respect from that observed at standard weather stations – such as those at Heathrow Airport.

The route of the walk from Finsbury Square to the River Thames

1. Finsbury Square. The first stop is an open, green square, just on the border between the borough of Islington and the City of London. The width of the square is about 120m, and the surrounding buildings are all approximately the same height (25-30m), and are continuous along the length of the roads on each side.

The square’s dimensions allow it an expansive view of the sky – so it receives sunlight for much of the day – but provides little shelter from the wind. Much of the central square is covered with grass, which moderates the surface temperature. In addition, there are trees to offer shade, and to screen the area from traffic noise and pollutants. We would expect this square to warm and cool more quickly than other, more densely built, parts of the city.

We walk south toward Moorgate, via a typical city street – terraced buildings of uniform height, separated by a street about as wide as the buildings are tall – an urban canyon. There is no vegetation along its length, and a great deal of pedestrian and vehicular traffic uses this route.

The north-south orientation of the street, and its dimensions, mean that it is almost always in shadow, except around noon. All the buildings here have a commercial function, and are occupied during the daytime. The offices on the west side get morning sun and are warmed, while those on the east side are in shadow during the morning – and vice versa in the afternoon. This street offers some shelter from the prevailing westerly winds, which also means that the pollutants from vehicles can accumulate near breathing level.

We proceed eastwards, to South Place.

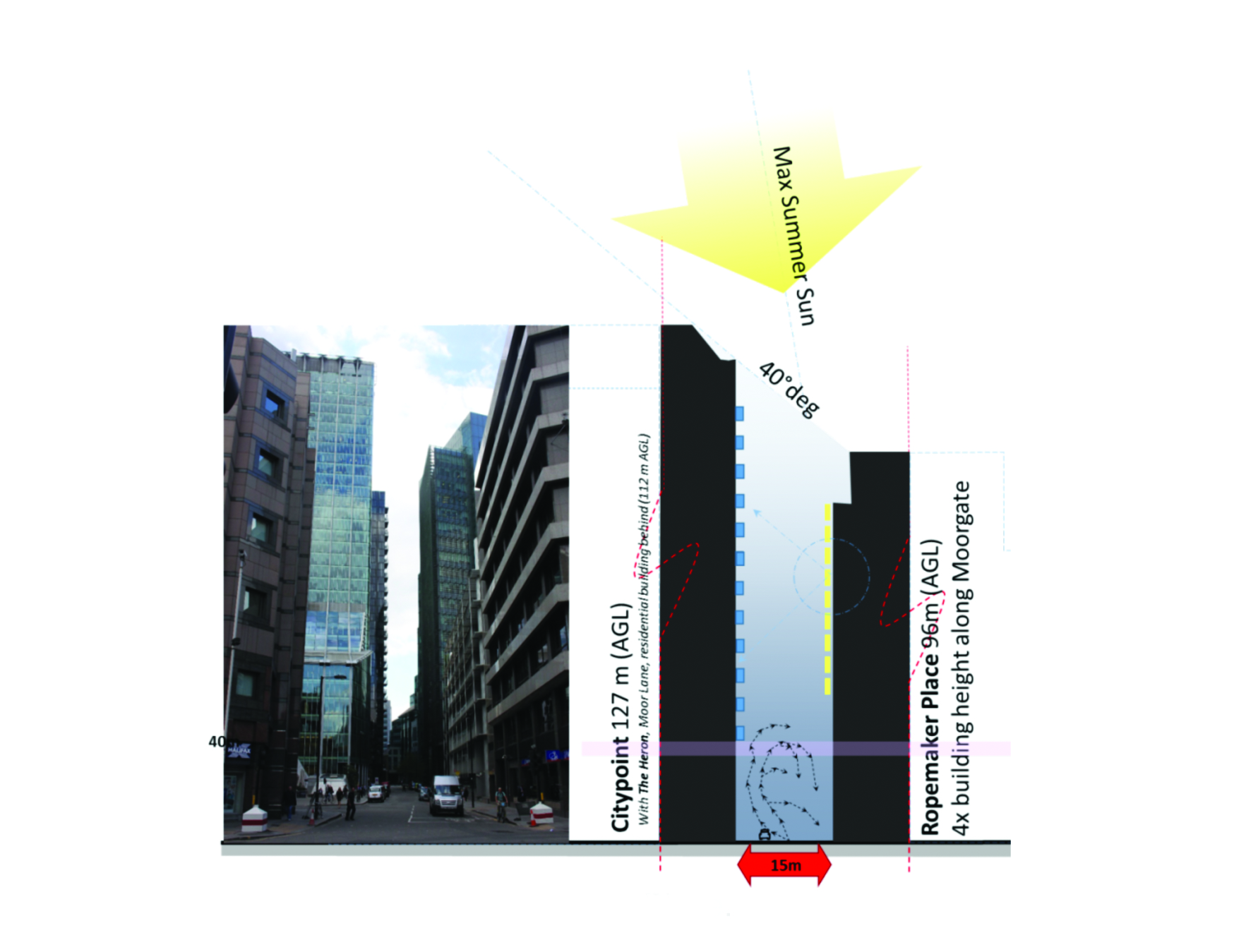

2. South Place, looking towards Ropemaker Place

Looking west along Chiswell Street, the urban landscape has changed significantly; very tall buildings, many clad in glass, form a narrow canyon.

At ground level, there is little solar access as the buildings on the south side shade the façade of those on the north side for much of the year. You can make out the balconies of an apartment block on the south-side façade that will rarely experience direct sunlight because of its aspect; one wonders if these balconies are much used.

Limited sunlight penetrates the canyon of buildings on Chiswell Street

This building acts as a shading device for the glass-walled office across the street. Is there a case for the position of these building types to be reversed, so that the offices get the shade needed and the apartments receive sunshine?

We turn left down Bloomfield Street towards London Wall. You may feel a sharp increase in wind as the prevailing westerly airflow is channelled along this thoroughfare. The buildings on this street are lower, and many are of pre-1960s construction; the differences may be best illustrated by the windows, which can be opened, allowing for natural ventilation, but also potentially introducing outside noise and polluted air.

This street curves southwards toward Bishopsgate, and the cluster of tall buildings that are redefining the urban landscape of the City of London.

100 Bishopsgate will soon shade Heron Tower's PVs

3. The Heron tower

At the corner of Wormwood Street and Bishopsgate, we have a good view of the Heron Tower, which is remarkable only for its size, standing more than 180m tall. On its south façade, embedded in its glass wall, are photovoltaic cells that allow it to gather nearly 2.5% of its energy via on-site renewables. However, there is no right to solar energy, and the building planned for 100 Bishopsgate will shade this energy-generating façade, instantly neutralising a significant part of its ‘green’ credentials.

The route continues south along Wormwood Street, then right into St Mary Axe, which brings us past Norman Foster’s building – 30 St Mary Axe (the ‘Gherkin’), with its unusual, aerodynamic shape. Its tapered form ensures that, despite its height, the view of the sky vault at ground level is relatively expansive. On the few occasions when rain falls on calm days, the shape of the building creates a halo effect on the ground, as the slight bulge in its envelope shelters the surrounding ground.

4. The corner of St Mary Axe and Leadenhall Street

This is the heart of the eastern cluster, with an assortment of very tall buildings, including two of Richard Rogers’ designs – the Leadenhall Building (the ‘Cheesegrater’– Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners) and the Lloyd’s Building (the ‘inside-out building’).

Wind speeds increase in gaps between buildings

The juxtaposition of tall buildings here creates a great variety of conditions on the ground, depending on the direction of the wind and the position of the sun. In some places, the wind is squeezed between buildings, creating a Venturi effect and unpleasant gusty conditions at the ground. One should note the glass canopy that extends from the façade of the Cheesegrater, and shelters the ground from fast-moving air streaming down its face.

There is a small square at the intersection here, which has seating, but one wonders how much it is used because it offers little protection from the elements. A new tower planned for this area (52-54 Lime Street), will change the climate dynamics of this area yet again.

The route continues onto Fenchurch Street, which takes us to another recent addition to the tall buildings of London.

5. Philpot Lane

At 20 Fenchurch Street is a remarkable building by Rafael Viñoly; clad in glass, its floorspace increases with height – to maximise the value of office space – thereby creating its distinctive shape and moniker, the ‘Walkie-Talkie’. Atop its 37 storeys is a restaurant and garden that are open to the public.

To ensure its completion, the City of London became a partner to acquire the ‘right to light’ of affected buildings. However, it was not its shading effects that gained international attention – quite the reverse; during a sunny September 2013, the solar beam on the curved, south-facing façade was concentrated and reflected downward, onto the pavement and buildings of adjacent Eastcheap. The intensity of the solar energy was sufficient to melt parts of a Jaguar car, to singe carpet in a barber’s shop and even to cook eggs.

Some have blamed global warming for the event, but the cause was immutable solar geometry and a lacuna in design thinking; along with the Heron Building, it demonstrates the relationship between buildings in an urban setting. It has taken a major investment to fix the problem.

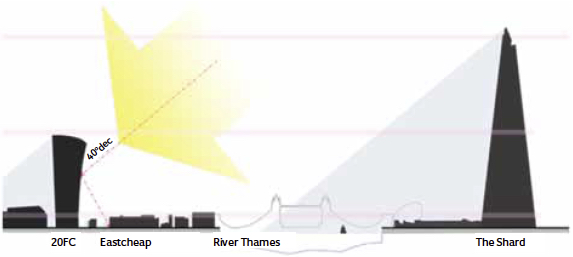

We continue along Eastcheap, turning onto St Mary’s Lane, crossing over Lower Thames street, and down to the Thames, shown in a north to south cross-section of the Thames – extending from 20 Fenchurch Street to The Shard – below. The arrow depicts the altitude angle of the sun at noon, at the time of the summer equinox.

6. Overlooking the Thames and The Shard

The final stop is on the Thames embankment. On the far side of the river, the 300m-tall, glass-sheathed Shard rises impressively above the surrounding landscape. Its shape belies its immensity; its shadow at noon will extend more than 350m for half of the year.

Further east along the Embankment, you can see the Strata building to the South. It has three turbines at roof level, which can access the much-faster winds that gust above the rooftops of buildings. If the heights of the surrounding buildings increase, of course, this renewable resource will become diminished. In any case, since its completion, the blades have barely turned!

Julie Futcher is an architect at Urban Generation and Gerald Mills is an urban climatologist and lecturer at University College Dublin